(Permanent) Army Training leading up to the Winter War?

Conclusion: The uses of War Heroes

Conclusion: The uses of War Heroes

The heroic status of the Jäger Officers was an important part of the process of merging the forces of nationalism and conscription to create the new Finnish Army. Post World War I, Armies were no longer small permanent forces where the soldiers were “mercenaries, criminals, vagabonds and destitutes.” Instead, they were volunteers or conscripted citizen-soldiers, respectable citizens of their communities. Their dying in war mattered to these communities in quite a different way to the deaths of soldiers drawn from the margins of society in the pre-WWI era. As entire nations had to be mobilised for war in the new era of mass armies, death on the battlefield had to be given a higher meaning. The reality of the war experience was transformed into “the Myth of the War Experience”, which looked back upon war as a meaningful event that made life worthwhile for conscripts and provided a mass feeling of national unity. This mythical notion of war, which grew and developed throughout the nineteenth century, was a key factor behind the war enthusiasm that swept over Europe in August 1914.

There was a need on the home front and among the veterans to find a higher meaning in reyurn for the losses and suffering. The Myth of the War Experience provided this. Through the eternal commemoration of the dead by the whole nation after the war, the fallen would be made “immortal.” Those who were active in the construction of the myth were a rather small number of articulate middle-class men who had often volunteered for the war. “The aim was to make an inherently unpalatable past acceptable, important not just for the purpose of consolation, but above all for the justification of the nation in whose name the war had been fought.” The heroic narratives about the Finnish Jägers can be read against this cultural background, as an attempt to construct a purposeful story about national warriors, national struggle and ultimate victory out of the events of the Civil War of 1918, which was largely experienced as frightening, shameful, humiliating and traumatising. The Jägers’ hero myth can be seen as helping society deal with the grief of the dead soldiers’ families; constructing a national self-image of Finland as a “ nation”; and mobilising a patriotic readiness to fight and sacrifice anew.

As the Jägers and their supporters immediately started preparing the country’s defence for another war against Russia, there was a great need for continued patriotic mobilisation. As the narrators of the Jäger myth were anxious that the nation should recover from one war and prepare for the next war, there was a need for something similar to the Myth of the War Experience. In the Finnish case, it was an image of the Finnish “Liberation War” as a noble and meaningful fight and the patriotic sacrifices made there served as models for a possible war with Russia. The Jäger narrative could also be used to direct public attention away from the internal conflict towards the perceived conflict between Finland and Russia. According to the Jäger story, the Jägers’ “invincible wrath” had been directed against Russia all along and continued to be now that the nation was independent - but in the nationalist world-view, constantly threatened from the East.

The need presented by military educational thinkers to educate a “new” kind of Finnish citizen-soldier and transform conscripts into “new human beings” through military training can be read as an extension of the Jäger hero narrative. The Jägers were exceptional men, but in order to fight a modern war against Russia, every Finnish soldier had to be trained to achieve the same level of patriotism and spirit of self-sacrifice that drove the Jägers. This was a difficult undertaking for the conscript army, and a daring promise to make. It meant enormous demands on the training officers supposed to succeed in this task, but also implied that the men fit for that task – the Jägers themselves – were national heroes not only in wartime, but in peacetime as well. Although many dead heroes were commemorated and honoured, living heroes making splendid military careers in the brand-new national armed forces probably catered better to the need to optimistically look towards a rosy national future rather than back at the painful war between brothers. The Jäger heroism was about spirit of self-sacrifice, a journey into the unknown, hardships and ordeals, but also about home-coming, victory, success and prestige in post-war society.

For conscripts who were to be educated into citizen-soldiers in interwar Finland, this perhaps made the Jägers more attractive military models than the fallen heroes of the war, no matter how gloriously they had died. Yet as we have seen, the Jägers’ public image was not completely free from shadows and contradictions. This Post has mainly looked at the crafting of the Jäger myth, not its reception. The fraught political situation meant that the Jägers were “impossible heroes” for a large part of the population. Their militancy, harshness and at times ruthless selfrighteousness also made for a frightening edge to the Jäger image. However, in spite of these cracks in the idealised image, and the differences among the Jägers as real-life military educators, the Jägers’ story communicated an enormous faith in the military and in the moral power of idealistic patriotism and self-sacrifice. This applies to all the three aspects of the Jäger image analysed in this chapter – the heroic war narrative, the image of the Jägers as post-war officers with a “national spirit”, as well as the Jägers’ patriotic spirit of self-sacrifice as a guiding-star for the conception of a “modern” national citizen-soldier.

When they set out for their journey, the future Jägers had oftentimes been confronted with a strong scepticism against their venture and a solid reluctance to gain political solutions based on military violence. In post-war society, there was, as we have seen, still a strong resistance against the militarisation of society. Through the Jäger myth, the Jägers and their supporters asserted an image of the citizen-as-soldier as the foundation of civic society and national independence, an image much resisted in Finnish society, yet also very influential. Within the constory of interwar

nationalism and the gendered division of labour in the defence of the nation – men and boys training for combat in the army and civil guards, women and girls working with auxiliary tasks in Lotta Svärd – the Jäger story offered both men and women the security of belonging to an national collective superior in strength and virtue to others.

The heroic status of the Jäger Officers was an important part of the process of merging the forces of nationalism and conscription to create the new Finnish Army. Post World War I, Armies were no longer small permanent forces where the soldiers were “mercenaries, criminals, vagabonds and destitutes.” Instead, they were volunteers or conscripted citizen-soldiers, respectable citizens of their communities. Their dying in war mattered to these communities in quite a different way to the deaths of soldiers drawn from the margins of society in the pre-WWI era. As entire nations had to be mobilised for war in the new era of mass armies, death on the battlefield had to be given a higher meaning. The reality of the war experience was transformed into “the Myth of the War Experience”, which looked back upon war as a meaningful event that made life worthwhile for conscripts and provided a mass feeling of national unity. This mythical notion of war, which grew and developed throughout the nineteenth century, was a key factor behind the war enthusiasm that swept over Europe in August 1914.

There was a need on the home front and among the veterans to find a higher meaning in reyurn for the losses and suffering. The Myth of the War Experience provided this. Through the eternal commemoration of the dead by the whole nation after the war, the fallen would be made “immortal.” Those who were active in the construction of the myth were a rather small number of articulate middle-class men who had often volunteered for the war. “The aim was to make an inherently unpalatable past acceptable, important not just for the purpose of consolation, but above all for the justification of the nation in whose name the war had been fought.” The heroic narratives about the Finnish Jägers can be read against this cultural background, as an attempt to construct a purposeful story about national warriors, national struggle and ultimate victory out of the events of the Civil War of 1918, which was largely experienced as frightening, shameful, humiliating and traumatising. The Jägers’ hero myth can be seen as helping society deal with the grief of the dead soldiers’ families; constructing a national self-image of Finland as a “ nation”; and mobilising a patriotic readiness to fight and sacrifice anew.

As the Jägers and their supporters immediately started preparing the country’s defence for another war against Russia, there was a great need for continued patriotic mobilisation. As the narrators of the Jäger myth were anxious that the nation should recover from one war and prepare for the next war, there was a need for something similar to the Myth of the War Experience. In the Finnish case, it was an image of the Finnish “Liberation War” as a noble and meaningful fight and the patriotic sacrifices made there served as models for a possible war with Russia. The Jäger narrative could also be used to direct public attention away from the internal conflict towards the perceived conflict between Finland and Russia. According to the Jäger story, the Jägers’ “invincible wrath” had been directed against Russia all along and continued to be now that the nation was independent - but in the nationalist world-view, constantly threatened from the East.

The need presented by military educational thinkers to educate a “new” kind of Finnish citizen-soldier and transform conscripts into “new human beings” through military training can be read as an extension of the Jäger hero narrative. The Jägers were exceptional men, but in order to fight a modern war against Russia, every Finnish soldier had to be trained to achieve the same level of patriotism and spirit of self-sacrifice that drove the Jägers. This was a difficult undertaking for the conscript army, and a daring promise to make. It meant enormous demands on the training officers supposed to succeed in this task, but also implied that the men fit for that task – the Jägers themselves – were national heroes not only in wartime, but in peacetime as well. Although many dead heroes were commemorated and honoured, living heroes making splendid military careers in the brand-new national armed forces probably catered better to the need to optimistically look towards a rosy national future rather than back at the painful war between brothers. The Jäger heroism was about spirit of self-sacrifice, a journey into the unknown, hardships and ordeals, but also about home-coming, victory, success and prestige in post-war society.

For conscripts who were to be educated into citizen-soldiers in interwar Finland, this perhaps made the Jägers more attractive military models than the fallen heroes of the war, no matter how gloriously they had died. Yet as we have seen, the Jägers’ public image was not completely free from shadows and contradictions. This Post has mainly looked at the crafting of the Jäger myth, not its reception. The fraught political situation meant that the Jägers were “impossible heroes” for a large part of the population. Their militancy, harshness and at times ruthless selfrighteousness also made for a frightening edge to the Jäger image. However, in spite of these cracks in the idealised image, and the differences among the Jägers as real-life military educators, the Jägers’ story communicated an enormous faith in the military and in the moral power of idealistic patriotism and self-sacrifice. This applies to all the three aspects of the Jäger image analysed in this chapter – the heroic war narrative, the image of the Jägers as post-war officers with a “national spirit”, as well as the Jägers’ patriotic spirit of self-sacrifice as a guiding-star for the conception of a “modern” national citizen-soldier.

When they set out for their journey, the future Jägers had oftentimes been confronted with a strong scepticism against their venture and a solid reluctance to gain political solutions based on military violence. In post-war society, there was, as we have seen, still a strong resistance against the militarisation of society. Through the Jäger myth, the Jägers and their supporters asserted an image of the citizen-as-soldier as the foundation of civic society and national independence, an image much resisted in Finnish society, yet also very influential. Within the constory of interwar

nationalism and the gendered division of labour in the defence of the nation – men and boys training for combat in the army and civil guards, women and girls working with auxiliary tasks in Lotta Svärd – the Jäger story offered both men and women the security of belonging to an national collective superior in strength and virtue to others.

ex Ngāti Tumatauenga ("Tribe of the Maori War God") aka the New Zealand Army

Training the Conscript Citizen-Soldier (in the 1920’s)

Training the Conscript Citizen-Soldier (in the 1920’s)

The Finnish Army faced enormous challenges in the interwar years. It was supposed to organise and prepare for defending the country against vastly superior Russian forces. It had to train whole generations of young Finnish men into skilled soldiers and equip them for combat. Furthermore, it was expected to turn these men into the kind of highly motivated, patriotic, self-motivated and self-sacrificing modern national warriors envisioned by the Jägers and other officers in the younger generation. The starting point was none too promising, due to the criticism and scepticism in the political arena towards protracted military service within the cadre army system. Many conscripts from a working class background had all too probably seized on at least some of the socialists’ anti-militaristic or even pacifistic agitation against armies in general and bourgeois cadre armies in particular. Neither could conscripts from the areas of society supporting the Agrarian Party be expected to arrive at the barracks unprejudiced and open-minded. Although conscripts from families who were small freeholders usually supported the Civil Guards, they were not necessarily positive about military service within the cadre army, especially during the first years of its existence. In consequence, a majority of the conscripts, particularly in the 1920’s, could be expected to have an “attitude problem”. Some of the greatest challenges facing the conscript army were therefore to prove its efficiency as a military training organisation, convince suspicious conscripts and doubtful voters of its commitment to democracy, and demonstrate its positive impact on conscripts.

Although it was often claimed that military training as such would foster mature and responsible citizens – giving the conscripts discipline, obedience and punctuality as well as instilling consideration for the collective interest – officers and pro-defence nationalists with educationalist inclinations did not place their trust in close-order drill and field exercises alone. More had to be done. From the point of view of army authorities and other circles supportive of the regular army, there was an urgent need to “enlighten” the conscript soldiers. They had to be “educated” into adopting a positive attitude towards not only military service and the cadre army system, but also towards their other civic duties within the new “white” national state. This Post examines the attempts of officers, military priests and educationalists to offer the conscripts images of soldiering that would not only make conscripts disciplined, motivated and efficient soldiers, but also help the conscript army overcome its “image problems” and help the nation overcome its internal divisions. The Post’s focus is therefore not on the methods or practices of the educational efforts directed at the conscripts in military training, but on the ideological contents of these efforts, mainly as manifested in the intertwined representations of soldiering and citizenship in the army’s magazine for soldiers Suomen Sotilas (Finland’s Soldier).

Civic education and the Suomen Sotilas magazine

The 1919 report produced by a committee appointed by the Commander of the Armed Forces to organise the “spiritual care” of the conscripted soldiers expressed both the concerns felt over the soldiers’ attitude towards their military service and the solutions envisioned. The report stressed the importance in modern war of “the civil merit of an army, its spiritual strength”. In the light of “recent events” the committee pointed to the risks of arming men without making sure that they had those civil merits – a reference to the Civil War, perhaps, or to the participation of conscripted soldiers in the recent communist revolutions in Russia, Germany and other Central European countries. The report stated, “the stronger the armed forces are technically, the greater the danger they can form to their own country in case of unrest, unless they are inspired by high patriotic and moral principles that prevent them from surrendering to support unhealthy movements within the people”. The committee members – two military priests, two Jäger officers and one elementary school inspector – saw the remedy as teaching the conscripts basic knowledge about the fatherland and its history, giving those who lacked elementary education basic skills in reading, writing and mathematics, and providing the soldiers with other “spiritual pursuits”, which mainly meant various religious services. Quoting the commander of the armed forces, General K.F. Wilkama, the committee supported the notion that the army should be a “true institution of civic education”. Its optimistic report expressed a remarkably strong faith in the educational potential of military service:

These educational aspirations should be seen not only within the framework of not only the military system, but also as a part of the ngoing concerns among the Finnish educated classes over the civic education and political loyalties of the working class ever since the end of the nineteenth century. Urbanisation, industrialisation and democratisation made the perceived “irrationality” and “uncivilised” state of the masses seem ever more threatening to the elite. In

face of the pressure towards “Russification” during the last decades of Russian rule, and the subsequent perceived threat from Soviet Russia, this anxiety over social upheaval was translated into an anxiety over national survival. Historian Pauli Arola has argued that the attempt by Finnish politicians to introduce compulsory elementary education in 1907 – after decades of political debate, but only one year after universal franchise was introduced – should be seen within the constory of these feelings of threat. Once the “common people” had the vote, educating them into “loyalty” in accordance with the upper classes’ notions of the “nation” and its existing social order became a priority. Resistance from imperial authorities stopped the undertaking in 1907, but Finnish educationalists continued to propagate for increased civic education through-out the school system.

The civil war only intensified the urgency of the educated elite’s agenda of educating the rebellious elements among the Finnish people. The intellectuals of “white” Finland described these as primitive, brutal, even bestial, hooligans who for lack of discipline and culture had become susceptible to Russian influences and given free rein to the worst traits in the Finnish national character. There was a special concern over children from socialist environments and the orphan children of red guardsmen who had died in the war or perished in the prison camps. When compulsory education was finally introduced in 1921, the curriculum for schools in rural districts, where most Finns then lived, was strongly intent on conserving the established social order. It idealised traditional country life in opposition to “unsound” urbanisation and emphasised the teaching of Christian religion and domestic history. In the same spirit, civic education was from the outset included in the training objectives of the conscript army. “Enlightenment lectures”, also called “citizen education”, were incorporated in the conscripts’ weekly programme. These lectures were sometimes given by officers, but mainly by military priests (who were also assigned the duty of teaching illiterate conscripts to read and write. As elementary schooling was only made compulsory in 1921, the army throughout the interwar period received conscripts who had never attended elementary school. The share of illiterate conscripts was however only 1–2%, peaking in 1923 and thereafter rapidly declining. Nevertheless, in 1924 elementary teaching still took up ten times as many working hours for the military priests as their “enlightenment work”). In 1925, the Commander of the armed forces issued a detailed schedule for these lectures. The conscripts should be given 45 hours of lectures on the “history of the fatherland”, 25 hours on civics, 12 hours on Finnish literary history and 10 hours of lectures on “temperance and morality”. Taken together, roughly two working weeks during the one-year military service were consequently allocated for civic education. In addition, the pastoral care of the soldiers, in the form of evening prayers and divine service both in the garrisons and training camps, was seen as an important part of “enlightening” soldiers. A consciousness of the nation’s past and religious piety were evidently een as the two main pillars of patriotism, law-abidingness and loyalty to the existing social order. (The dean of the military priests Artur Malin presented the ongoing civic education work in the army in an article in the Suomen Sotilas magazine in 1923. He listed the following subjects: reading, writing, mathematics, geography, history, civics, natural history, singing, handicraft and temperance education).

The Army’s Magazine for Soldiers

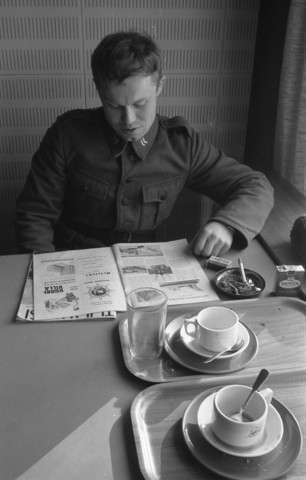

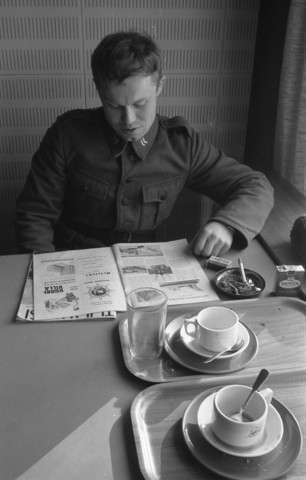

In most army garrisons and camps, local female volunteers provided a service club or “Soldiers’ home”. These establishments offered coffee, lemonade and bakeries, but also intellectual stimulus in the form of newspapers, magazines and small libraries. Any socialist or otherwise “unpatriotic” publications were unthinkable in these recreational areas where the conscripts spent much of their leisure hours. However, one of the publications the conscripts would most certainly find at the “Soldiers’ Home”, if it wasn’t already distributed to the barracks, was the weekly magazine Suomen Sotilas (Finland’s Soldier). This illustrated magazine contained a mixture of editorials on morality, military virtues and the dangers of Bolshevism, entertaining military adventure stories, and articles on different Finnish military units, sports within the armed forces, military history, weaponry and military technology. There were reviews on recommended novels and open letters from “concerned fathers” or “older soldiers”, exhorting the conscripts to exemplary behaviour, as well as a dedicated page for cartoons and jokes about military life. The interwar volumes of Suomen Sotilas serve as a good source on the “enlightenment” and “civic education” directed at the conscript soldiers within the military system. Through its writers, the magazine was intimately connected with the command of the armed forces, yet formally it was published by an independent private company.

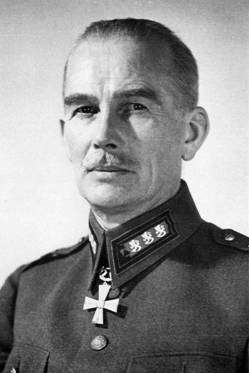

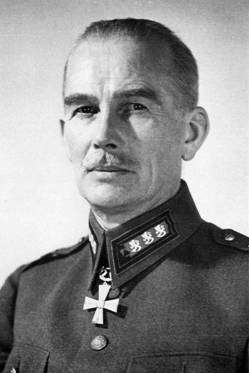

The editors in chief were literary historian Ilmari Heikinheimo (1919–1922), student of law and later Professor of Law Arvo Sipilä (1922–1925), M.A. Emerik Olsoni (1926) and army chaplain, later Dean of the Army Chaplains Rolf Tiivola (1927–1943). Important writers who were also Jäger officers were Veikko Heikinheimo, military historian and Director of the Cadet School Heikki Nurmio, Army Chaplains Hannes Anttila and Kalervo Groundstroem, as well as Aarne Sihvo, Director of the Military Academy and later Commander of the Armed Forces. Articles on new weaponry and military technology were written by several Jäger officers in the first years the magazine was published; a.o. Lennart Oesch, Eino R. Forsman [Koskimies], Verner Gustafsson, Bertel Mårtensson, Väinö Palomäki, Lars Schalin, Arthur Stenholm [Saarmaa], Kosti Pylkkänen and Ilmari Järvinen. All of these officers had successful military careers, reaching the rank of Lieutenant Colonel or higher. In the last number of the first volume of 1919, the editors published the photographs of 13 of the magazine’s “most eager collaborators”. Out of these 13, nine were officers, five were Jäger officers. The five civilians were a Master of Arts, two Doctors of Philosophy and one clergyman.

The initiative for starting the magazine originally came from the war ministry and the contents of each number were initially examined before publication by ministry officials. In 1919–1921, the magazine was published by a small publishing house for popular enlightenment, Edistysseurojen (as this publisher went bankrupt in 1923, the editors formed a public limited company, ‘Kustannus Oy Suomen Mies’ (~Finland’s Man Publishing Company Ltd.) which took over the magazine. On the tenth anniversary of the magazine’s founding, its chief accountant complained that the state had not subsidised the magazine at all in 1919–1925 and then only granted a minimal subsidy) and regular writers were mostly nationalist officers of the younger generation, many of them either Jäger officers or military priests. Civilians – professional authors, historians, educators and clergymen – also wrote for the magazine, but usually more occasionally rather than regularly. In spite of different backgrounds and experiences, the contributors had a lot in common; they were generally educated middle-class men who shared a staunchly non-socialist and nationalist political outlook. Contributions from female authors were not unheard of, but rarely occurred. Although the magazine was meant to be published weekly, it was published fortnightly over several long periods. The support of private business was important for its economy, both through advertising revenue and gift subscriptions to the military units paid for by defence-friendly businessmen. The magazine started out with a circulation of 4 000 in 1919 and rose to over 12,000 by mid-1920. This caused the editors to proudly exclaim: “Now it can be said with certainty that Suomen Sotilas falls into the hands of every soldier and civil guardsman.” After the magazine’s first 18 months these rather frequent notices on the circulation ceased to appear, probably indicating that the circulation had started to decline. Originally aimed at a readership of both conscripts and civic guards, the magazine had to give in to the tough competition from other magazines for Suojeluskuntas readership after a few years. It then concentrated on being the army’s magazine for soldiers.

The contents of Suomen Sotilas not only express the hopes and objectives of some of the same people who were in charge of training and educating the conscripted soldiers, but also their concerns and fears with regard to conscripts. In its first number, the editors of Suomen Sotilas proclaimed that the ambition of the magazine was to “make the men in the ranks good human beings, good citizens and good soldiers”. Its writings should serve “general civic education and completely healthy spiritual development” and strive towards “the fatherland in its entirety becoming dear to and worth defending for our soldiers.” A concern about lacking patriotism or even hostility towards the national armed forces can, however, be read between these lines. This concern did not diminish much during the 1920’s, but was stated even more explicitly by the former editor-in-chief Arvo Sipilä (1898–1974) in the magazine’s tenth anniversary issue in

December 1928: “It is well known, that among the youths liable for military service there are quite a number of such persons for whom the cause of national defence has remained alien, not to speak of those, who have been exposed to influences from circles downright hostile to national defence. In this situation, it is the natural task of a soldiers’ magazine to guide these soldiers’ world of ideas towards a healthy national direction, in an objective and impartial way, to touch that part in their emotional life, which in every true Finnish heart is receptive to the concept of a common fatherland (…)”

The editors of Suomen Sotilas were painfully aware of the popular and leftist criticism of circumstances and abuses in the army throughout the 1920’s. In 1929 an editorial lamented, “the civilian population has become used to seeing the army simply as an apparatus of torture, the military service as both mentally and physically monotonous, the officers as beastlike, the [army’s] housekeeping and health care as downright primitive.” The same story greeted the recent PR drive of the armed forces, inviting the conscripts’ relatives into the garrisons for “family days”. There, the editorial claimed, they would see for themselves that circumstances were much better than rumour would have it. The initiative behind these “family days”, however, arose from the officers’ intense concerns over the popular image of the conscript army17 – concerns that were also mirrored in the pages of Suomen Sotilas (According to historian Veli-Matti Syrjö, the ”family days” was an initiative by Lieutenant-Colonel Eino R. Forsman. In his proposal, Forsman pointed out how an understanding between his regiment and the civilian population in its district was obstructed by popular ignorance).

Turning a Conscript into a Citizen-Soldier

In the autumn of 1922, the First Pioneer Battalion in the city of Viipuri arranged a farewell ceremony for those conscript soldiers who had served a full year and were now leaving the army. On this occasion, the top graduate of the Finnish Army’s civic education training gave an inspiring speech to his comrades. – At least, so it must have seemed to the officers listening to Pioneer Kellomäki’s address, since they had it printed in Suomen Sotilas for other soldiers around the country to meditate upon. This private told his comrades that the time they had spent together in the military might at times have felt arduous, yet “everything in life has its price, and this is the price a people has to pay for its liberty”. Moreover, he thought that military training had no doubt done the conscripts well, although it had often been difficult and disagreeable: “You leave here much more mature for life than you were when you arrived. Here, in a way, you have met the reality of life, which most of you knew nothing about as you grew up in your childhood homes. Here, independent action has often been demanded of you. You have been forced to rely on your own strengths and abilities. Thereby, your will has been fortified and your self-reliance has grown. In winning his own trust, a man wins a great deal. He wins more strength, more willpower and vigour, whereas doubt and shyness make a man weak and ineffective. You leave here both physically hardened and spiritually strengthened.” This talented young pioneer had managed to adopt a way of addressing his fellow soldiers that marked many ideological storys in Suomen Sotilas. He was telling them what they themselves had experienced and what it now meant to them, telling them who they were as citizens and soldiers. His speech made use of two paired concepts that often occurred in the interwar volumes of the magazine. He claimed that military education was a learning process where conscripts grew into maturity and furthermore, that the virtues of the good soldier, obtainable through military training, were also the virtues of a useful and successful citizen.

What supposedly happened to conscripts during their military service that made them “much more mature for life”? In the army, conscripts allegedly learned punctuality, obedience and order, “which is a blessing for all the rest of one’s life”. Sharing joys and hardships in the barracks taught equality and comradeship. “Here, there are no class differences.” The exercises, athletics and strict order in the military made the soldiers return “vigorous and polite” to their home districts, admired by other young people for their “light step and their vivid and attentive eye.” Learning discipline and obedience drove out selfishness from the young man and instilled in him a readiness to make sacrifices for the fatherland. The duress of military life hardened the soldier, strengthened his selfconfidence and made “mother’s boys into men with willpower and Stamina.” The thorough elementary and civic education in the army offered possibilities even for illiterates to succeed in life and climb socially (1929).24 The order, discipline, exactitude, cleanliness, considerateness, and all the knowledge and technical skills acquired in the military were a “positive capital” of “incalculable future benefit” for every conscript – there was “good reason to say that military service is the best possible school for every young man, it is a real school for men, as it has been called.” “If we had no military training, an immense number of our conscripts would remain good-for-nothings; slouching and drowsy beings hardly able to support themselves. [The army] is a good school and luckily every healthy young man has the opportunity to attend it.” (All quotes from various articles in Suomen Sotilas magazine).

It is noteworthy how the rhetoric in Suomen Sotilas about military service improving conscripts’s minds and bodies usually emphasised the civic virtues resulting from military training. Military education was said to develop characteristics in conscripts that were useful to themselves later in life and beneficial for civil society in general. Conscripts being discharged in 1922 were told that experience from the previous armed forces in Finland had proven that the sense of duty, exactitude and purposefulness in work learnt in military service ensured future success in civilian life as well. If the conscripts wanted to succeed in life, they should preserve the values and briskness they had learnt in the army, “in one word, you should still be soldiers”. Such rhetoric actually implied that the characteristics of a good soldier and a virtuous citizen were one and the same. As the recruit became a good soldier, he simultaneously developed into a useful patriotic citizen. The Finnish Army, an editorial in 1920 stated, “is an educational institution to which we send our sons with complete trust, in one of the decisive periods of their lives, to develop into good proper soldiers and at the same time honourable citizens. Because true military qualities are in most cases also most important civic qualities.” If the army fulfilled this high task well, the story continued, the millions spent in tax money and working hours withheld would not have been wasted, but would “pay a rich dividend.”

Storys in this vein were most conspicuous in Suomen Sotilas during the early 1920’s, as conscription was still a highly controversial issue and heated debates over the shaping of military service went on in parliament. In 1922, just when the new permanent conscription law was waiting for a final decision after the up-coming elections, an editorial in the magazine expressed great concerns over the possibly imminent shortening of military service. The editors blamed the “suspicious attitude” among the public towards the conscript army on negative prejudices caused by the old imperial Russian military. The contemporary military service, they claimed, was something quite different. It was a time when conscripts “become tame”, realised their duty as defenders of the fatherland, improved their behavior and were united across class borders as they came to understand and appreciate each other’s interests and opinions. All these positive expectations can be read as mirroring anxieties among the educated middle classes over continued class conflicts in the wake of the Civil War and the lack of patriotism and a “sense of duty” among conscripts in the working classes. The assurances that military service would inevitably induce the right, “white” kind of patriotism and civic virtue in conscripts and unite them in military comradeship appear to be fearful hopes in disguise.

As late as 1931, the conservative politician Paavo Virkkunen wrote in Suomen Sotilas that the bitterness “still smouldering in many people’s mind” after the events in 1918 had to give place for “positive and successful participation in common patriotic strivings”. He saw conscripts divided by political differences and hoped that they would be united by the common experience of military service, “a time of learning patriotic condition” and “a fertile period of brotherly

comradeship and spiritual confluence.”

(Image Sourced from http://www.eduskunta.fi/fakta/edustaja/kuvat/911749.jpg)

Paavo Virkkunen (27 September 1874, Pudasjärvi – 13 July 1959, Pälkäne) was a Finnish conservative politician. He was a member of the Finnish Party and was elected in the parliament in 1914, but joined the National Coalition Party (Kokoomus) in 1919. He was five times the Speaker of the Parliament. He became the chairman of the party in 1932 following the six year leadership of Kyösti Haataja.

Physical Education

Moral education and physical development were closely intertwined in the public portrayal of how military service improved conscripts. The military exercises, it was claimed, would make the conscripts’ bodies strong, healthy and proficient. In 1920, the committee for military matters in parliament made a statement about the importance for national security of physical education for conscripts. Pleading to the government to make greater efforts in this area, the committee pointed out how games, gymnastics and athletics not only generated the “urge for deeds, drive, toughness and readiness for military action” in the nation’s youth, but also developed discipline, self-restraint and a spirit of sacrifice. The conscript should be physically trained and prepared for a future war in the army, as well as being developed and disciplined into a moral, industrious and productive citizen. The militarily trained conscript, claimed Suomen Sotilas in 1920, was handsome and energetic, aesthetically balanced, harmonious, lithe and springy – unlike the purely civilian citizen, who was marked by clumsiness, stiff muscles and a shuffling gait.

According to Klaus U. Suomela, a leading figure in Finnish gymnastics writing in the magazine in 1923, the lack of proper military education and the hard toiling in agriculture and forestry had given many Finns a bad posture and unbalanced bodily proportions. Their arms, shoulders and backs were overdeveloped in relation to the lower extremities. Gymnastics to the pace of brisk commands as well as fast ball games and athletics would rectify these imperfections and force the Finns, “known to be sluggish in their thinking”, to speed up their mental activities, Suomela stated. He admitted that “the Finnish quarrelsomeness” would be worsened by individual sports, but this would be counteracted by group gymnastics and team games. Suomela seems to have viewed Finnish peasant boys from the vantage point of the athletic ideals of the educated classes, emphasising slenderness, agility and speed, and found them too “rough-hewn and marked by heavy labour”.

After independence and the Civil War, Finnish military and state authorities immediately saw a connection between security policy, public health and physical education. Officers and sports leaders debated how gymnastics and athletics formed the foundations for military education. Proposals to introduce military pre-education for boys in the school system were never realised, but physical education in elementary schools and the civil guards nonetheless emphasized competitive and physically tough sports in the 1920’s and 1930’. These “masculine” sports were thought to develop the strength and endurance needed for soldiering. Light gymnastics, on the other hand, were considered more appropriate for in schoolgirls, developing “feminine” characteristics such as bodily grace, nimbleness and adaptation to the surrounding group. Sports and athletics were given lavish attention in Suomen Sotilas.

The magazine reported extensively on all kinds of sports competitions within the armed forces, publishing detailed accounts and photographs of the victors. Sports were evidently assumed to interest the readership, but the editors also attached symbolical and political importance to sports as an arena of national integration. An editorial in 1920 claimed that in the army sports competitions, ”Finland’s men could become brothers” as officers and soldiers, workers and capitalists competed in noble struggle. “There is a miniature of Finland’s sports world such as we want to see it – man against man in comradely fight, forgetful of class barriers and class hate. May the soldiers take this true sporting spirit with them into civilian life when they leave military service.” Hopes were expressed that conscripts, permeated with a patriotic sense of duty after receiving their military education, would continue practicing sports and athletics in their home districts, not only to stay fit as soldiers and useful citizens, but also in order to spread models for healthy living and physical fitness among the whole people.

The Immaturity of Recruits

The rhetoric about the army as a place where boys became men and useful, responsible citizens required a denial of the maturity and responsibility of those who had not yet done their military service. The 21-year old recruits who arrived for military training, many of them after years of employment, often in physically demanding jobs requiring self-management and responsibility, were directly or indirectly portrayed as somehow less than men, as immature youngsters who had not yet developed either the physique or the mind of a real man. In this constory, the writers in Suomen Sotilas took the moral position of older and wiser men who implicitly claimed to possess the knowledge and power to judge young soldiers in this respect. Any critique or resistance against the methods of military service was dismissed and ridiculed as evidence of immaturity or lack of toughness. “You know very well that perpetual whining does not befit a man, only women do that”, wrote an anonymous “Reservist” in 1935 – i.e. somebody claiming to already have done his military training. An “Open letter to my discontented son who is doing his military service” in 1929 delivered a paternal dressing-down to any reluctant conscript, claiming that the only cause for discontent with army life was a complete lack of “sense of duty”. The military, however, provided a healthy education in orderliness and the fulfilling of one’s duties, taking one’s place in the line “like every honourable man”.

This immaturity of the Finnish conscript was sometimes described as not only a matter of individual development, but also associated with traits of backwardness in Finnish culture and society, which could, however, be compensated for both in individuals and the whole nation by the salubrious effects of military training. It was a recurring notion that Finns in layers of society without proper education had an inclination to tardiness, slackness and quarrelsomeness. This echoed concerns over negative traits in the Finnish national character that had increased ever since the nationalist mobilisation against the Russian “oppression” encountered popular indifference. The spread of socialism, culminating in the rebellion of 1918, made the Finnish people seem ever more undisciplined and inclined to envy, distrustfulness and deranged fanaticism in the eyes of the educated elites. In an article published in 1919, Arvi Korhonen (1897–1967), a history student and future professor who had participated in the Jäger movement as a recruiter, complained about the indolence and lack of proficiency and enterprise of people in the Finnish countryside.

(Source: http://www.hum.utu.fi/oppiaineet/yleine ... honen.jpeg)

Arvi Korhonen: History Student, History Professor and WW2 Intelligence Officer

Korhonen called for military discipline and order as a remedy for these cultural shortcomings. “Innumerable are those cases where military service has done miracles. Lazybones have returned to their home district as energetic men, and the bosses of large companies say they can tell just from work efficiency who has been a soldier.” Korhonen claimed that similar observations were common enough – he was evidently thinking of either experiences from the “old” conscript army in Finland or from other countries – to show that “the army’s educational importance is as great as its significance for national defence.” Another variation on this theme ascribed a kind of primordial and unrefined vitality to Finnish youngsters, which had to be shaped or hardened by military training in order to result in conduct and become useful for society. The trainer of the Finnish Olympic wrestling team Armas Laitinen wrote an article in this vein in 1923, explaining why the military service was a particularly suitable environment to introduce conscripts to wrestling: “Almost without exception, healthy conscripts arrive to the ranks and care of the army. The simple youngsters of backwoods villages arrive there to fulfil their civic duty, children of the wilds and remote hamlets, whose cradle stood in the middle of forests where they grew to men, healthy, rosy-cheeked and sparkling with zest for life. In the hard school of the army they are brought up to be men, in the true sense of the word, and that common Finnish sluggishness and listlessness is ground away. Swiftness, moderation and above all vigour are imprinted on these stiff tar stumps and knotty birch stocks. They gradually achieve their purpose – readiness. The army has done its great work. A simple child of the people has grown up to a citizen aware of his duty, in which the conscious love of nationalism has been rooted forever.”

Jäger lieutenant and student of theology Kalervo Groundstroem (1894–1966) was even less respectful towards the recruits when he depicted the personal benefits of military training in 1919. In the army, he wrote, everything is done rapidly and without any loitering, “which can feel strange especially for those from the inner parts of the country”.

(Source: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/c ... alervo.jpg)

Jääkärikapteeni Kalervo Groundstroem: Lauri Kalervo Groundstroem myöh. Kurkiala (16. marraskuuta 1894 Längelmäki - 26. joulukuuta 1966.

“It is very salutary that many country boys, who all their lives have just been laying comfortably next to the fireplace, at last get a chance to rejuvenate and slim themselves. And we can only truly rejoice that numerous bookworms and spoilt, sloppy idlers get an airing by doing field service. Barracks life and the healthy influence of comradeship rub off smallmindedness, selfishness, vanity and other “sharp edges” in a young man’s character”, claimed Groundstroem. Military training is therefore “a useful preparation for future life.” Moving in step with others, the soldiers acquire a steady posture, their gaze is strengthened, their skin gets the right colour, they always have a healthy appetite, and flabby muscles are filled out and tightened. The finest result of this education, however, is the “unflinching sense of duty” it brings forth. The “sense of duty” mentioned in many of the quotes above stands out as the most important shared quality or virtue of the ideal soldier and citizen. From this military and civic virtue, the other characteristics of a good soldier and a good citizen quoted so far could be derived, such as self-restraint, a spirit of sacrifice, order and discipline, punctuality and exactitude in the performance of assigned tasks, unselfishness and submitting to the collective good, etc. The writers in Suomen Sotilas usually positioned themselves through their storys as superior to the readers in knowing what duty meant and hence entitled, indeed obliged, to educate the readers, who were positioned as thoughtless yet corrigible youngsters. In the constory of Suomen Sotilas, references to “a sense of duty” conveyed a message to the individual man that he needed to submit himself and his actions in the service of something higher and larger than his own personal desires and pleasures – submit to the army discipline and to the hardships and dangers of soldiering.

The Finnish Army faced enormous challenges in the interwar years. It was supposed to organise and prepare for defending the country against vastly superior Russian forces. It had to train whole generations of young Finnish men into skilled soldiers and equip them for combat. Furthermore, it was expected to turn these men into the kind of highly motivated, patriotic, self-motivated and self-sacrificing modern national warriors envisioned by the Jägers and other officers in the younger generation. The starting point was none too promising, due to the criticism and scepticism in the political arena towards protracted military service within the cadre army system. Many conscripts from a working class background had all too probably seized on at least some of the socialists’ anti-militaristic or even pacifistic agitation against armies in general and bourgeois cadre armies in particular. Neither could conscripts from the areas of society supporting the Agrarian Party be expected to arrive at the barracks unprejudiced and open-minded. Although conscripts from families who were small freeholders usually supported the Civil Guards, they were not necessarily positive about military service within the cadre army, especially during the first years of its existence. In consequence, a majority of the conscripts, particularly in the 1920’s, could be expected to have an “attitude problem”. Some of the greatest challenges facing the conscript army were therefore to prove its efficiency as a military training organisation, convince suspicious conscripts and doubtful voters of its commitment to democracy, and demonstrate its positive impact on conscripts.

Although it was often claimed that military training as such would foster mature and responsible citizens – giving the conscripts discipline, obedience and punctuality as well as instilling consideration for the collective interest – officers and pro-defence nationalists with educationalist inclinations did not place their trust in close-order drill and field exercises alone. More had to be done. From the point of view of army authorities and other circles supportive of the regular army, there was an urgent need to “enlighten” the conscript soldiers. They had to be “educated” into adopting a positive attitude towards not only military service and the cadre army system, but also towards their other civic duties within the new “white” national state. This Post examines the attempts of officers, military priests and educationalists to offer the conscripts images of soldiering that would not only make conscripts disciplined, motivated and efficient soldiers, but also help the conscript army overcome its “image problems” and help the nation overcome its internal divisions. The Post’s focus is therefore not on the methods or practices of the educational efforts directed at the conscripts in military training, but on the ideological contents of these efforts, mainly as manifested in the intertwined representations of soldiering and citizenship in the army’s magazine for soldiers Suomen Sotilas (Finland’s Soldier).

Civic education and the Suomen Sotilas magazine

The 1919 report produced by a committee appointed by the Commander of the Armed Forces to organise the “spiritual care” of the conscripted soldiers expressed both the concerns felt over the soldiers’ attitude towards their military service and the solutions envisioned. The report stressed the importance in modern war of “the civil merit of an army, its spiritual strength”. In the light of “recent events” the committee pointed to the risks of arming men without making sure that they had those civil merits – a reference to the Civil War, perhaps, or to the participation of conscripted soldiers in the recent communist revolutions in Russia, Germany and other Central European countries. The report stated, “the stronger the armed forces are technically, the greater the danger they can form to their own country in case of unrest, unless they are inspired by high patriotic and moral principles that prevent them from surrendering to support unhealthy movements within the people”. The committee members – two military priests, two Jäger officers and one elementary school inspector – saw the remedy as teaching the conscripts basic knowledge about the fatherland and its history, giving those who lacked elementary education basic skills in reading, writing and mathematics, and providing the soldiers with other “spiritual pursuits”, which mainly meant various religious services. Quoting the commander of the armed forces, General K.F. Wilkama, the committee supported the notion that the army should be a “true institution of civic education”. Its optimistic report expressed a remarkably strong faith in the educational potential of military service:

These educational aspirations should be seen not only within the framework of not only the military system, but also as a part of the ngoing concerns among the Finnish educated classes over the civic education and political loyalties of the working class ever since the end of the nineteenth century. Urbanisation, industrialisation and democratisation made the perceived “irrationality” and “uncivilised” state of the masses seem ever more threatening to the elite. In

face of the pressure towards “Russification” during the last decades of Russian rule, and the subsequent perceived threat from Soviet Russia, this anxiety over social upheaval was translated into an anxiety over national survival. Historian Pauli Arola has argued that the attempt by Finnish politicians to introduce compulsory elementary education in 1907 – after decades of political debate, but only one year after universal franchise was introduced – should be seen within the constory of these feelings of threat. Once the “common people” had the vote, educating them into “loyalty” in accordance with the upper classes’ notions of the “nation” and its existing social order became a priority. Resistance from imperial authorities stopped the undertaking in 1907, but Finnish educationalists continued to propagate for increased civic education through-out the school system.

The civil war only intensified the urgency of the educated elite’s agenda of educating the rebellious elements among the Finnish people. The intellectuals of “white” Finland described these as primitive, brutal, even bestial, hooligans who for lack of discipline and culture had become susceptible to Russian influences and given free rein to the worst traits in the Finnish national character. There was a special concern over children from socialist environments and the orphan children of red guardsmen who had died in the war or perished in the prison camps. When compulsory education was finally introduced in 1921, the curriculum for schools in rural districts, where most Finns then lived, was strongly intent on conserving the established social order. It idealised traditional country life in opposition to “unsound” urbanisation and emphasised the teaching of Christian religion and domestic history. In the same spirit, civic education was from the outset included in the training objectives of the conscript army. “Enlightenment lectures”, also called “citizen education”, were incorporated in the conscripts’ weekly programme. These lectures were sometimes given by officers, but mainly by military priests (who were also assigned the duty of teaching illiterate conscripts to read and write. As elementary schooling was only made compulsory in 1921, the army throughout the interwar period received conscripts who had never attended elementary school. The share of illiterate conscripts was however only 1–2%, peaking in 1923 and thereafter rapidly declining. Nevertheless, in 1924 elementary teaching still took up ten times as many working hours for the military priests as their “enlightenment work”). In 1925, the Commander of the armed forces issued a detailed schedule for these lectures. The conscripts should be given 45 hours of lectures on the “history of the fatherland”, 25 hours on civics, 12 hours on Finnish literary history and 10 hours of lectures on “temperance and morality”. Taken together, roughly two working weeks during the one-year military service were consequently allocated for civic education. In addition, the pastoral care of the soldiers, in the form of evening prayers and divine service both in the garrisons and training camps, was seen as an important part of “enlightening” soldiers. A consciousness of the nation’s past and religious piety were evidently een as the two main pillars of patriotism, law-abidingness and loyalty to the existing social order. (The dean of the military priests Artur Malin presented the ongoing civic education work in the army in an article in the Suomen Sotilas magazine in 1923. He listed the following subjects: reading, writing, mathematics, geography, history, civics, natural history, singing, handicraft and temperance education).

The Army’s Magazine for Soldiers

In most army garrisons and camps, local female volunteers provided a service club or “Soldiers’ home”. These establishments offered coffee, lemonade and bakeries, but also intellectual stimulus in the form of newspapers, magazines and small libraries. Any socialist or otherwise “unpatriotic” publications were unthinkable in these recreational areas where the conscripts spent much of their leisure hours. However, one of the publications the conscripts would most certainly find at the “Soldiers’ Home”, if it wasn’t already distributed to the barracks, was the weekly magazine Suomen Sotilas (Finland’s Soldier). This illustrated magazine contained a mixture of editorials on morality, military virtues and the dangers of Bolshevism, entertaining military adventure stories, and articles on different Finnish military units, sports within the armed forces, military history, weaponry and military technology. There were reviews on recommended novels and open letters from “concerned fathers” or “older soldiers”, exhorting the conscripts to exemplary behaviour, as well as a dedicated page for cartoons and jokes about military life. The interwar volumes of Suomen Sotilas serve as a good source on the “enlightenment” and “civic education” directed at the conscript soldiers within the military system. Through its writers, the magazine was intimately connected with the command of the armed forces, yet formally it was published by an independent private company.

The editors in chief were literary historian Ilmari Heikinheimo (1919–1922), student of law and later Professor of Law Arvo Sipilä (1922–1925), M.A. Emerik Olsoni (1926) and army chaplain, later Dean of the Army Chaplains Rolf Tiivola (1927–1943). Important writers who were also Jäger officers were Veikko Heikinheimo, military historian and Director of the Cadet School Heikki Nurmio, Army Chaplains Hannes Anttila and Kalervo Groundstroem, as well as Aarne Sihvo, Director of the Military Academy and later Commander of the Armed Forces. Articles on new weaponry and military technology were written by several Jäger officers in the first years the magazine was published; a.o. Lennart Oesch, Eino R. Forsman [Koskimies], Verner Gustafsson, Bertel Mårtensson, Väinö Palomäki, Lars Schalin, Arthur Stenholm [Saarmaa], Kosti Pylkkänen and Ilmari Järvinen. All of these officers had successful military careers, reaching the rank of Lieutenant Colonel or higher. In the last number of the first volume of 1919, the editors published the photographs of 13 of the magazine’s “most eager collaborators”. Out of these 13, nine were officers, five were Jäger officers. The five civilians were a Master of Arts, two Doctors of Philosophy and one clergyman.

The initiative for starting the magazine originally came from the war ministry and the contents of each number were initially examined before publication by ministry officials. In 1919–1921, the magazine was published by a small publishing house for popular enlightenment, Edistysseurojen (as this publisher went bankrupt in 1923, the editors formed a public limited company, ‘Kustannus Oy Suomen Mies’ (~Finland’s Man Publishing Company Ltd.) which took over the magazine. On the tenth anniversary of the magazine’s founding, its chief accountant complained that the state had not subsidised the magazine at all in 1919–1925 and then only granted a minimal subsidy) and regular writers were mostly nationalist officers of the younger generation, many of them either Jäger officers or military priests. Civilians – professional authors, historians, educators and clergymen – also wrote for the magazine, but usually more occasionally rather than regularly. In spite of different backgrounds and experiences, the contributors had a lot in common; they were generally educated middle-class men who shared a staunchly non-socialist and nationalist political outlook. Contributions from female authors were not unheard of, but rarely occurred. Although the magazine was meant to be published weekly, it was published fortnightly over several long periods. The support of private business was important for its economy, both through advertising revenue and gift subscriptions to the military units paid for by defence-friendly businessmen. The magazine started out with a circulation of 4 000 in 1919 and rose to over 12,000 by mid-1920. This caused the editors to proudly exclaim: “Now it can be said with certainty that Suomen Sotilas falls into the hands of every soldier and civil guardsman.” After the magazine’s first 18 months these rather frequent notices on the circulation ceased to appear, probably indicating that the circulation had started to decline. Originally aimed at a readership of both conscripts and civic guards, the magazine had to give in to the tough competition from other magazines for Suojeluskuntas readership after a few years. It then concentrated on being the army’s magazine for soldiers.

The contents of Suomen Sotilas not only express the hopes and objectives of some of the same people who were in charge of training and educating the conscripted soldiers, but also their concerns and fears with regard to conscripts. In its first number, the editors of Suomen Sotilas proclaimed that the ambition of the magazine was to “make the men in the ranks good human beings, good citizens and good soldiers”. Its writings should serve “general civic education and completely healthy spiritual development” and strive towards “the fatherland in its entirety becoming dear to and worth defending for our soldiers.” A concern about lacking patriotism or even hostility towards the national armed forces can, however, be read between these lines. This concern did not diminish much during the 1920’s, but was stated even more explicitly by the former editor-in-chief Arvo Sipilä (1898–1974) in the magazine’s tenth anniversary issue in

December 1928: “It is well known, that among the youths liable for military service there are quite a number of such persons for whom the cause of national defence has remained alien, not to speak of those, who have been exposed to influences from circles downright hostile to national defence. In this situation, it is the natural task of a soldiers’ magazine to guide these soldiers’ world of ideas towards a healthy national direction, in an objective and impartial way, to touch that part in their emotional life, which in every true Finnish heart is receptive to the concept of a common fatherland (…)”

The editors of Suomen Sotilas were painfully aware of the popular and leftist criticism of circumstances and abuses in the army throughout the 1920’s. In 1929 an editorial lamented, “the civilian population has become used to seeing the army simply as an apparatus of torture, the military service as both mentally and physically monotonous, the officers as beastlike, the [army’s] housekeeping and health care as downright primitive.” The same story greeted the recent PR drive of the armed forces, inviting the conscripts’ relatives into the garrisons for “family days”. There, the editorial claimed, they would see for themselves that circumstances were much better than rumour would have it. The initiative behind these “family days”, however, arose from the officers’ intense concerns over the popular image of the conscript army17 – concerns that were also mirrored in the pages of Suomen Sotilas (According to historian Veli-Matti Syrjö, the ”family days” was an initiative by Lieutenant-Colonel Eino R. Forsman. In his proposal, Forsman pointed out how an understanding between his regiment and the civilian population in its district was obstructed by popular ignorance).

Turning a Conscript into a Citizen-Soldier

In the autumn of 1922, the First Pioneer Battalion in the city of Viipuri arranged a farewell ceremony for those conscript soldiers who had served a full year and were now leaving the army. On this occasion, the top graduate of the Finnish Army’s civic education training gave an inspiring speech to his comrades. – At least, so it must have seemed to the officers listening to Pioneer Kellomäki’s address, since they had it printed in Suomen Sotilas for other soldiers around the country to meditate upon. This private told his comrades that the time they had spent together in the military might at times have felt arduous, yet “everything in life has its price, and this is the price a people has to pay for its liberty”. Moreover, he thought that military training had no doubt done the conscripts well, although it had often been difficult and disagreeable: “You leave here much more mature for life than you were when you arrived. Here, in a way, you have met the reality of life, which most of you knew nothing about as you grew up in your childhood homes. Here, independent action has often been demanded of you. You have been forced to rely on your own strengths and abilities. Thereby, your will has been fortified and your self-reliance has grown. In winning his own trust, a man wins a great deal. He wins more strength, more willpower and vigour, whereas doubt and shyness make a man weak and ineffective. You leave here both physically hardened and spiritually strengthened.” This talented young pioneer had managed to adopt a way of addressing his fellow soldiers that marked many ideological storys in Suomen Sotilas. He was telling them what they themselves had experienced and what it now meant to them, telling them who they were as citizens and soldiers. His speech made use of two paired concepts that often occurred in the interwar volumes of the magazine. He claimed that military education was a learning process where conscripts grew into maturity and furthermore, that the virtues of the good soldier, obtainable through military training, were also the virtues of a useful and successful citizen.

What supposedly happened to conscripts during their military service that made them “much more mature for life”? In the army, conscripts allegedly learned punctuality, obedience and order, “which is a blessing for all the rest of one’s life”. Sharing joys and hardships in the barracks taught equality and comradeship. “Here, there are no class differences.” The exercises, athletics and strict order in the military made the soldiers return “vigorous and polite” to their home districts, admired by other young people for their “light step and their vivid and attentive eye.” Learning discipline and obedience drove out selfishness from the young man and instilled in him a readiness to make sacrifices for the fatherland. The duress of military life hardened the soldier, strengthened his selfconfidence and made “mother’s boys into men with willpower and Stamina.” The thorough elementary and civic education in the army offered possibilities even for illiterates to succeed in life and climb socially (1929).24 The order, discipline, exactitude, cleanliness, considerateness, and all the knowledge and technical skills acquired in the military were a “positive capital” of “incalculable future benefit” for every conscript – there was “good reason to say that military service is the best possible school for every young man, it is a real school for men, as it has been called.” “If we had no military training, an immense number of our conscripts would remain good-for-nothings; slouching and drowsy beings hardly able to support themselves. [The army] is a good school and luckily every healthy young man has the opportunity to attend it.” (All quotes from various articles in Suomen Sotilas magazine).

It is noteworthy how the rhetoric in Suomen Sotilas about military service improving conscripts’s minds and bodies usually emphasised the civic virtues resulting from military training. Military education was said to develop characteristics in conscripts that were useful to themselves later in life and beneficial for civil society in general. Conscripts being discharged in 1922 were told that experience from the previous armed forces in Finland had proven that the sense of duty, exactitude and purposefulness in work learnt in military service ensured future success in civilian life as well. If the conscripts wanted to succeed in life, they should preserve the values and briskness they had learnt in the army, “in one word, you should still be soldiers”. Such rhetoric actually implied that the characteristics of a good soldier and a virtuous citizen were one and the same. As the recruit became a good soldier, he simultaneously developed into a useful patriotic citizen. The Finnish Army, an editorial in 1920 stated, “is an educational institution to which we send our sons with complete trust, in one of the decisive periods of their lives, to develop into good proper soldiers and at the same time honourable citizens. Because true military qualities are in most cases also most important civic qualities.” If the army fulfilled this high task well, the story continued, the millions spent in tax money and working hours withheld would not have been wasted, but would “pay a rich dividend.”

Storys in this vein were most conspicuous in Suomen Sotilas during the early 1920’s, as conscription was still a highly controversial issue and heated debates over the shaping of military service went on in parliament. In 1922, just when the new permanent conscription law was waiting for a final decision after the up-coming elections, an editorial in the magazine expressed great concerns over the possibly imminent shortening of military service. The editors blamed the “suspicious attitude” among the public towards the conscript army on negative prejudices caused by the old imperial Russian military. The contemporary military service, they claimed, was something quite different. It was a time when conscripts “become tame”, realised their duty as defenders of the fatherland, improved their behavior and were united across class borders as they came to understand and appreciate each other’s interests and opinions. All these positive expectations can be read as mirroring anxieties among the educated middle classes over continued class conflicts in the wake of the Civil War and the lack of patriotism and a “sense of duty” among conscripts in the working classes. The assurances that military service would inevitably induce the right, “white” kind of patriotism and civic virtue in conscripts and unite them in military comradeship appear to be fearful hopes in disguise.

As late as 1931, the conservative politician Paavo Virkkunen wrote in Suomen Sotilas that the bitterness “still smouldering in many people’s mind” after the events in 1918 had to give place for “positive and successful participation in common patriotic strivings”. He saw conscripts divided by political differences and hoped that they would be united by the common experience of military service, “a time of learning patriotic condition” and “a fertile period of brotherly

comradeship and spiritual confluence.”

(Image Sourced from http://www.eduskunta.fi/fakta/edustaja/kuvat/911749.jpg)

Paavo Virkkunen (27 September 1874, Pudasjärvi – 13 July 1959, Pälkäne) was a Finnish conservative politician. He was a member of the Finnish Party and was elected in the parliament in 1914, but joined the National Coalition Party (Kokoomus) in 1919. He was five times the Speaker of the Parliament. He became the chairman of the party in 1932 following the six year leadership of Kyösti Haataja.

Physical Education

Moral education and physical development were closely intertwined in the public portrayal of how military service improved conscripts. The military exercises, it was claimed, would make the conscripts’ bodies strong, healthy and proficient. In 1920, the committee for military matters in parliament made a statement about the importance for national security of physical education for conscripts. Pleading to the government to make greater efforts in this area, the committee pointed out how games, gymnastics and athletics not only generated the “urge for deeds, drive, toughness and readiness for military action” in the nation’s youth, but also developed discipline, self-restraint and a spirit of sacrifice. The conscript should be physically trained and prepared for a future war in the army, as well as being developed and disciplined into a moral, industrious and productive citizen. The militarily trained conscript, claimed Suomen Sotilas in 1920, was handsome and energetic, aesthetically balanced, harmonious, lithe and springy – unlike the purely civilian citizen, who was marked by clumsiness, stiff muscles and a shuffling gait.

According to Klaus U. Suomela, a leading figure in Finnish gymnastics writing in the magazine in 1923, the lack of proper military education and the hard toiling in agriculture and forestry had given many Finns a bad posture and unbalanced bodily proportions. Their arms, shoulders and backs were overdeveloped in relation to the lower extremities. Gymnastics to the pace of brisk commands as well as fast ball games and athletics would rectify these imperfections and force the Finns, “known to be sluggish in their thinking”, to speed up their mental activities, Suomela stated. He admitted that “the Finnish quarrelsomeness” would be worsened by individual sports, but this would be counteracted by group gymnastics and team games. Suomela seems to have viewed Finnish peasant boys from the vantage point of the athletic ideals of the educated classes, emphasising slenderness, agility and speed, and found them too “rough-hewn and marked by heavy labour”.

After independence and the Civil War, Finnish military and state authorities immediately saw a connection between security policy, public health and physical education. Officers and sports leaders debated how gymnastics and athletics formed the foundations for military education. Proposals to introduce military pre-education for boys in the school system were never realised, but physical education in elementary schools and the civil guards nonetheless emphasized competitive and physically tough sports in the 1920’s and 1930’. These “masculine” sports were thought to develop the strength and endurance needed for soldiering. Light gymnastics, on the other hand, were considered more appropriate for in schoolgirls, developing “feminine” characteristics such as bodily grace, nimbleness and adaptation to the surrounding group. Sports and athletics were given lavish attention in Suomen Sotilas.

The magazine reported extensively on all kinds of sports competitions within the armed forces, publishing detailed accounts and photographs of the victors. Sports were evidently assumed to interest the readership, but the editors also attached symbolical and political importance to sports as an arena of national integration. An editorial in 1920 claimed that in the army sports competitions, ”Finland’s men could become brothers” as officers and soldiers, workers and capitalists competed in noble struggle. “There is a miniature of Finland’s sports world such as we want to see it – man against man in comradely fight, forgetful of class barriers and class hate. May the soldiers take this true sporting spirit with them into civilian life when they leave military service.” Hopes were expressed that conscripts, permeated with a patriotic sense of duty after receiving their military education, would continue practicing sports and athletics in their home districts, not only to stay fit as soldiers and useful citizens, but also in order to spread models for healthy living and physical fitness among the whole people.

The Immaturity of Recruits

The rhetoric about the army as a place where boys became men and useful, responsible citizens required a denial of the maturity and responsibility of those who had not yet done their military service. The 21-year old recruits who arrived for military training, many of them after years of employment, often in physically demanding jobs requiring self-management and responsibility, were directly or indirectly portrayed as somehow less than men, as immature youngsters who had not yet developed either the physique or the mind of a real man. In this constory, the writers in Suomen Sotilas took the moral position of older and wiser men who implicitly claimed to possess the knowledge and power to judge young soldiers in this respect. Any critique or resistance against the methods of military service was dismissed and ridiculed as evidence of immaturity or lack of toughness. “You know very well that perpetual whining does not befit a man, only women do that”, wrote an anonymous “Reservist” in 1935 – i.e. somebody claiming to already have done his military training. An “Open letter to my discontented son who is doing his military service” in 1929 delivered a paternal dressing-down to any reluctant conscript, claiming that the only cause for discontent with army life was a complete lack of “sense of duty”. The military, however, provided a healthy education in orderliness and the fulfilling of one’s duties, taking one’s place in the line “like every honourable man”.