Food rations in the Japanese forces

- Sewer King

- Member

- Posts: 1711

- Joined: 18 Feb 2004, 05:35

- Location: northern Virginia

Re: Food rations in the Japanese forces

Thanks to Taki for explaining in “Translations” thread that this comic is bilingual, as is the earlier one of the IJA field bakery. The red text is Chinese, with katakana subtitles alongside to show pronunciation.Peter H wrote:Meat portions being dried?Akira Takizawa wrote:They are not meat, but bread. It is the bread-eating race, which is a popular attraction in sports day.

I am guessing that those in the race had to bite the breads hanging from the strings, which would not be easy since the breads would swing all around.

- This is similar to apple-bobbing in the US/UK. Traditionally, floating apples must be picked up from a tub of water, without hands and using only the mouth. But there is a variation where the apples are hung from strings, like the bread in the Japanese game, and they are also hard to bite.

====================================

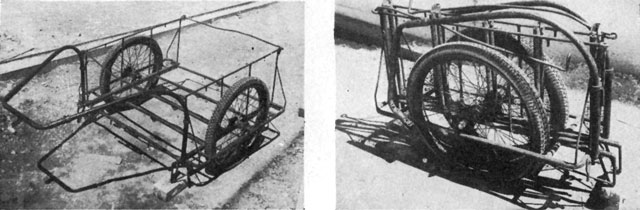

Isn't this a large one of the IJA's lightweight folding handcarts? What is their Japanese name?Peter H wrote:From ebay,seller spyfly03; This looks like a hot food transport cart of some kind also.

- A smaller handcart shown In the common US War Department Handbook of Japanese Military Forces, page 344:

Here the cart is full of cookpots, although they might be empty if large stockpots are hung up above smaller ones. Were these carts sometimes used to haul the wooden shokkan (food containers) from kitchen to barracks mess tables? Or, they might have been needed because of the wet ground seen here

Something is almost completely hidden behind the cart, which looks like it might be flying a small flag. The men themselves are not wearing field equipment or puttees, so they probably are in garrison?

====================================

Maybe no one could resist looking inside the bags before they are issued?Peter H wrote:Army comfort bags this time

Was the imonbukuro insprired by the French “comfort bag” of early World War I? They began with a Madame Balli who founded a civilian volunteer aid society for French troops at the time.

- From Atherton, Gertrude Franklin Horn. [url=http://www..munseys.com/diskfour/livpre.pdf]”The Living Present”[/url], page 5-7:

Some US troops of WW1's American Expeditionary Force also received comfort bags from Christian organizations. The practice might be traced back to the US Civil War and elsewhere. But it is the wide distribution of regular comfort bags by organized effort, especially by women's groups in France. This is what seems comparable to our earlier photo of Japanese volunteer women assembling imonbukuro.MADAME BALLI AND THE “COMFORT PACKAGE”

It was Madame Balli [a Parisian society woman] who invented the “comfort package” which other organizations have since developed into the “comfort bag” …

These packages, all neatly tied, and of varying sizes, were in the nature of surprise bags of an extremely practical order. Tobacco, pipes, cigarettes, chocolate, toothbrushes, soap, pocket-knives, combs. Safety-pins, handkerchiefs, needles-and-thread, buttons, pocket mirrors, post-cards, pencils, are a few of the articles …

The comfort packages are always given to the [soldiers] returning to their regiments on that particular day [of entrainment for the front]. They are piled high on a long table at one side of the barrack yard, [and they were handed out] with a “Bonne chance” as the men filed by. Some were sullen and unresponsive, but many more looked as pleased as children and no doubt were as excited over their “grabs,” which they were not to open until in the train. They would face death on the morrow, but for the moment at least they were personal and titillated ...

===================================

It seems a self-conscious posed photo for the Nationalist Chinese standard being held up in back. With no other information, I imagine the men are taking a break with cigarettes and one mess kit in sight. Since most of them have coats off, some with shirt sleeves rolled up, and almost no rifles or gear, maybe their break is from labor duty.Peter H wrote:1937 (Soldiers at rest)

-– Alan

- Akira Takizawa

- Member

- Posts: 3373

- Joined: 26 Feb 2006, 18:37

- Location: Japan

- Contact:

Re: Food rations in the Japanese forces

> In the bread-eating race, did the players have to do it standing on one foot?

In that picture, they seem to run on one foot. But, it is not a common rule in the bread-eating race.

> Isn't this a large one of the IJA's lightweight folding handcarts? What is their Japanese name?

It is called Riyaka in Japanese. Riyaka is a civilian commodity, though it was also used in the Army. Usually it is not folding. Folding Riyaka is a rare and special item for the Army.

http://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E3%83%AA% ... B%E3%83%BC

Taki

In that picture, they seem to run on one foot. But, it is not a common rule in the bread-eating race.

> Isn't this a large one of the IJA's lightweight folding handcarts? What is their Japanese name?

It is called Riyaka in Japanese. Riyaka is a civilian commodity, though it was also used in the Army. Usually it is not folding. Folding Riyaka is a rare and special item for the Army.

http://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E3%83%AA% ... B%E3%83%BC

Taki

- Sewer King

- Member

- Posts: 1711

- Joined: 18 Feb 2004, 05:35

- Location: northern Virginia

Re: Food rations in the Japanese forces

Thanks again Taki. Bread racing on one foot made the players hop. Though not a common rule, it either made the race more challenging, or just more humorous for the comic.

The Army's folding Riyaka is innovative, but it could have been less strong than the common fixed one because of its folding joints.

-- Alan

The Army's folding Riyaka is innovative, but it could have been less strong than the common fixed one because of its folding joints.

-- Alan

- Sewer King

- Member

- Posts: 1711

- Joined: 18 Feb 2004, 05:35

- Location: northern Virginia

Re: Food rations in the Japanese forces

Earlier, Taki explained that the IJA had studied its many observations from the Western Front of World War I. This included field messing. By the 1930s it developed dry combat rations in meal packages, probably the first of their kind among the world’s armies.

But the Army’s garrison food was also improved through this same time. From Katarzyna J. Cwiertka’s cultural study much quoted here, Modern Japanese Cuisine (London: Reaktion Press, 2006), pages 79-82:

Fortifying the soldiers' diet this way returns yet again to Taki's earlier explanation of why the Army compelled them to eat whale meat, which was not popular with the men but cheap for the Army budget.

On the subject of Japanese Navy curry, Hisashi mentioned earlier that serving it for Sunday meals helped finish off remaining vegetable supplies from the week before. Thrifty practices like this were probably common to garrison kitchens around the world.

I would expect that fried rice also served this same purpose at IJN tables, as it does elsewhere in Asia. It was one of the recipes listed in a 1935 survey of IJN sailors’ favorite dishes (Cwiertka, page 74).

====================================

-- Alan

But the Army’s garrison food was also improved through this same time. From Katarzyna J. Cwiertka’s cultural study much quoted here, Modern Japanese Cuisine (London: Reaktion Press, 2006), pages 79-82:

Elsewhere, Cwiertka noted that modern Japanese cuisine rests on a “tripod” of Japanese, Chinese, and Western influences. In the Imperial Japanese forces, this became institutional. At the time, the military was probably the one single institution that could have spread this so widely in Japan.Moulding the National Taste

The reforms of the 1920s in military catering largely contributed to the moulding of a nationally homogenous taste. They turned yoshoku items such as cutlet, stew and rice curry, into the hallmarks of military menus to accompany the go [approx ¾ cup] of rice-and-barley mixture served at every meal. These dishes had been already tried and tested, and adjusted to the preferences of the urban masses. This reduced the risk of them being rejected by the soldiers, as was the case with bread. After 1923 army reformers also began to incorporate Chinese dishes, inspired by the recent popularity of cheap Chinese eateries in Japanese cities … The introduction of Chinese food proved particularly successful because it was flavoured with soy sauce.

The 2,600 calorie value of the Japanese Army ration told here maintained the minimum 2,580 total reported in the 1904 war by US observer Colonel Havard, Coincidentally, it matched the 2,600 calories of the later “O ration” served to Japanese prisoners-of-war in US Army custody, also cited earlier.Contrary to the navy, which after adopting a Westernized diet in 1890 gradually returned to the native pattern based on rice and soy sauce, the foundation of the army diet rested firmly on the pre-modern urban meal pattern supplemented by Western and Chinese elements. The main reason that the armed forces included non-traditional dishes in their menus was because they provided more nourishment. Serving nourishing and filling meals at the lowest possible cost was the general rule of military cookery, and the adoption of Western and Chinese recipes made this possible. In 1910 the daily energy requirement for army soldiers was set at the level of 1,300-1,700 calories, and was raised in 1929 to 4,000 calories. Moreover, the authorities suggested that on the occasion of heavy training or a battle this standard should be further increased by 500-1300 calories. Approximately two-thirds of this amount was to be supplied by the staple, which left 1,200-1,300 calories (and in the case of heavy training or a battle even up to 2,600 calories) for side dishes.

Budgetary constraints made it virtually impossible to provide so many calories from lean traditional foodstuffs -- vegetables, tofu, and seafood. The best solution proved to be the large-scale adoption of foreign cooking techniques, such as deep-frying, pan-frying and stewing, and foreign ingredients, such as meat, lard, and potatoes. High-calorie fried dishes were a cheap source of energy, and also a method of using up ingredients of questionable quality -- practically everything qualified for being breaded and deep-fried ...

Fortifying the soldiers' diet this way returns yet again to Taki's earlier explanation of why the Army compelled them to eat whale meat, which was not popular with the men but cheap for the Army budget.

On the subject of Japanese Navy curry, Hisashi mentioned earlier that serving it for Sunday meals helped finish off remaining vegetable supplies from the week before. Thrifty practices like this were probably common to garrison kitchens around the world.

I would expect that fried rice also served this same purpose at IJN tables, as it does elsewhere in Asia. It was one of the recipes listed in a 1935 survey of IJN sailors’ favorite dishes (Cwiertka, page 74).

- Fried rice has the same flexibility in Asia as does pilaf in Arab and Turkic cuisines, pilau (or palow) in the Near East, paella in the Hispanic kitchen, and jambalaya or gumbo in Caribbean cooking. All of these are tasty one-pot complete meals based on rice, known to most everyone inside those cultures and many outside as well.

Moreover, fried rice can also be easily and quickly made in large quantities using a range of vegetables, meats, and seasonings, including leftovers, and still be acceptable to almost everyone.

====================================

Often it is said that spices once helped mask the smell or taste of foods on the verge of spoiling. Cwiertka includes it here. I am doubtful of this, in Japanese or any other cuisine. Even though in institutional cooking it is common to use low-quality ingredients in soups and stews, where they will be improved somewhat or at least hidden.... Moreover, adding curry powder to Japanese-style dishes perked up the bland taste of ingredients of inferior quality. Curry powder also helped to mask the unpleasant taste of spoiled fish and meat. In short, the military’s adoption of Chinese and Western dishes made a high-calorie diet economically possible.

- Across history, soldiers' food is usually not the best. But it would be different for a modern army to routinely serve its men near-spoiled meat. There are well-known stories about this from different armies and eras, many with truth in them. But they may have been more the exceptions that made good stories, rather than the rule.

Napoleon's famous saying that “an army marches on its stomach” has a corollary that it cannot march on its sick stomach. A commander might first call in the cook to answer for his men who went sick from food poisoning. If truly spoiled food is frequent, men will grumble early and could mutiny later; spoiled meat as trigger for the Imperial Russian Navy's Potempkin mutiny might be the best-known example of the latter.

- Some “hot” spices have vitamin and mineral value. But even this is incidental, though vital, because food cultures developed centuries before nutrition science did. The cuisines that use them knew nothing about actual vitamins, but sought the hot and spicy taste to counter the blandness of starchy staples and vegetables.

-- Alan

Re: Food rations in the Japanese forces

From the Asahi Shimbun archives.

I think this is after the 1945 surrender,demobbed soldiers.Looks like their cooking with small ceramic cookers of some sort.

I think this is after the 1945 surrender,demobbed soldiers.Looks like their cooking with small ceramic cookers of some sort.

- Attachments

-

- fr_1945.jpg (105.33 KiB) Viewed 3268 times

- Akira Takizawa

- Member

- Posts: 3373

- Joined: 26 Feb 2006, 18:37

- Location: Japan

- Contact:

Re: Food rations in the Japanese forces

They are Shichirin.Peter H wrote:Looks like their cooking with small ceramic cookers of some sort.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shichirin

Taki

- Sewer King

- Member

- Posts: 1711

- Joined: 18 Feb 2004, 05:35

- Location: northern Virginia

Re: Food rations in the Japanese forces

My thanks too, Taki. This also answers my question of what were the cookers used in a previous photo. Until now, and like many others, I had mistakenly thought of these as hibachi.

Were shichirin common or uncommon in Japanese Army field cooking? I wonder this because it seems heavy or bulky, and someone would have to carry it on the march.

====================================

If the photo shows demobilized IJA men in late 1945, maybe they are eating fairly well at the moment, in these hard times. Like so many other things, wasn't there a shortage of charcoal, as well as meat or poultry for grilling?

-- Alan

Were shichirin common or uncommon in Japanese Army field cooking? I wonder this because it seems heavy or bulky, and someone would have to carry it on the march.

====================================

If the photo shows demobilized IJA men in late 1945, maybe they are eating fairly well at the moment, in these hard times. Like so many other things, wasn't there a shortage of charcoal, as well as meat or poultry for grilling?

-- Alan

- Akira Takizawa

- Member

- Posts: 3373

- Joined: 26 Feb 2006, 18:37

- Location: Japan

- Contact:

Re: Food rations in the Japanese forces

> Were shichirin common or uncommon in Japanese Army field cooking? I wonder this because it seems heavy or bulky, and someone would have to carry it on the march.

Shichirin was not common in Japanese Army field cooking, because it was heavy to carry as you said.

> If the photo shows demobilized IJA men in late 1945, maybe they are eating fairly well at the moment, in these hard times. Like so many other things, wasn't there a shortage of charcoal, as well as meat or poultry for grilling?

Human must eat at any time. They would be cooking Yakitori.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yakitori

Taki

Shichirin was not common in Japanese Army field cooking, because it was heavy to carry as you said.

> If the photo shows demobilized IJA men in late 1945, maybe they are eating fairly well at the moment, in these hard times. Like so many other things, wasn't there a shortage of charcoal, as well as meat or poultry for grilling?

Human must eat at any time. They would be cooking Yakitori.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yakitori

Taki

Re: Food rations in the Japanese forces

Party time. :roll:

Re: Food rations in the Japanese forces

From ebay,seller tunasushi

Not all enjoyment required alcohol though

Not all enjoyment required alcohol though

- Sewer King

- Member

- Posts: 1711

- Joined: 18 Feb 2004, 05:35

- Location: northern Virginia

Re: Food rations in the Japanese forces

(First photo) From their shoulder straps the men look like the lowest-rank private soldiers. Maybe they are eating out, and not in garrison? Fresh fruit, at least.Peter H wrote:Party time

In peacetime at least, what chances did lowest ranks of IJA soldiers get to go and eat well like this, off-duty? From previous Navy photos, I had the impression that an NCO followed a party of lower-deck sailors even when on liberty ashore.

(Second photo) Thanks to Hisashi for explaining this photo in the “Translations” thread, that these are likely to be officer cadets. For them,

It looks like the three mounted “cavalrymen” might have just “charged” into the banquet. The middle “horse” may be rearing up. I think this was well-known in other armies too -- whether as “horseplay” as here, so to speak, or as hazing of recruits.hisashi wrote:… In IJA war school, their course just before the Pacific War was as follows;

About 100 days before the end of preliminary course, IJA told cadets their service-in-arm and regiment. Pupils prayed the appointment as they hoped to goodnesses they made up, such as 任地大明神.[ninchi daimyojin. “the goodness of the place of appointment” as printed in background] So cadets near the end of preliminary course were enjoying banquets. Some of them seemed hoping to be cavalrymen ...

- 24 months preliminary course

6 months service in various regiments as a private -> corporal

22 months standard course

====================================

Please note: the following citation is not for discussing any controversies about Nanking, or about Bataan. Those discussions belong elsewhere in the Forum and have many threads already.

Here the subject is only the provisioning of IJA forces in those campaigns. In line with Forum recommendations, this was first approved by a moderator before it was posted.

from Yamamoto, Masahiro. Nanking: Anatomy of an Atrocity (Praeger Publishing, 2000), pages 52-54:

Yamamoto cites official reports from the 6th, 9th, 16th, and 114th Divisions that elements of the CCAA sometimes outran their supply columns and ate commandeered food, which was plentiful enough along their advance. Major Cresswell noted that:When some troops [in central China] could not obtain necessary food and other materials, these items were sometimes supplied by airdrops. In many cases, however, the Japanese Army had to live off the land. Even General Matsui apparently hoped to procure a substantial amount of food in the enemy's territory. Although he worried about the supply situation in his diary on November 20, he quickly added, “We need not be concerned about the victuals despite the lack of supply because rice is plentiful in the areas where the troops are operating.“ Above all, the Japanese military leadership held to a principle that they would sacrifice food supply for effective military campaigning. The operation guideline of the Tenth Army immediately before its landing on November 5 said, “What is expected to be the most difficult problem in the coming campaign will be that of supply. Nevertheless, it is urgently necessary to carry out the operation … even by utilizing the logistical facilities almost solely for the transportation of ammunition while depending upon the local procuring for food.”

The CCAA [Central China Area Army, Naka Shina hōmen gun] set forth the same principle in its official guideline for the Nanking campaign, that is, it would give a logistical priority to ammunition, rather than food. A U.S. military attaché's report underlined this supply policy. According to Major Harry I. T. Cresswell, acting U.S. Military Attaché to China, the Japanese Army used horse-drawn carts as a major means of transportation and loaded most of the carts with ammunition and only a few with “rations for the men and forage for the animals.”

Airdropped IJA resupply is interesting because it was done on some scale, although we can’t tell here how large or small, or how often. Which was the first army to actually do this in combat operations – could it have been the IJA?... the Japanese infantry used anything that would roll, including ordinary baby buggies, rickshas, and low two-handled trucks. Furthermore, (Second) Lieutenant Miyamoto Shogo of 65th Infantry, 4th Company said “So many of our soldiers use the Chinese people [as porters] as well as their cows and horses that we are sometimes mistaken as Chinese troops.”

Since Taki said they were not so common in IJA use, the “low two-handled trucks” maybe did not mean the metal handcarts (Riyaka) noted earlier.

It was with the onset of combat, however, that soldiers soon became brutal. Both official reports of 16th Division and still other soldiers' diaries bear this out. 16th Div was especially concerned for the field army's discipline.Since the official policy [required each unit to feed itself], the officers and soldiers on the front did not seem to have any remorse about stealing food from the local population. Major Kusuki recorded the requisitioning of 800 bales of rice, 1,000 bales of wheat, 100 bales of sugar, and two motor vehicles in his diary on December 1 with a comment, “It has been fun.” Some officers were mindful of discipline problems related to the requisitioning. Lieutenant Colonel Terada Masao, a Tenth Army staff officer, wrote about the necessity of clearly distinguishing requisitioning from robbery. The staff chief of the 10th Division also maintained that it was necessary for responsible commanders to direct the requisitioning by issuing orders distinctly instead of leaving the matter to the soldiers' licentious acts. In many cases, however, requisitions simply became robbery. This was partly because in numerous instances requisition parties could not find anyone to negotiate with after the civilian population had fled with the approach of the battle. Yet one cannot deny that the Japanese soldiers became like a group of bandits. In a soldier's diary one could find such passages as “we brought to our unit a big pig we had found at a liquor store” or “the requisitions party returned with one hundred chickens.” A former soldier ... admitted that such plundering was the usual practice of the Japanese Army operating in China at that time. It is not surprising that some of those who became used to such a practice escalated their misbehavior …

… It is undeniable that the Japanese committed large-scale robbery on their march to Nanking in the name of requisition –- conduct rather comparable to the conduct of European troops in the Middle Ages than to … Union soldiers in Sherman's Army on their way to Savannah during the American Civil War.… This difference was attributable to a different motive for each: the Japanese robbed the local population for the sole purpose of feeding themselves, whereas the Union troops conducted a strategic destruction and made an effort to spare the lives of common people. Another factor was the more hostile environment faced by the Japanese.

The Japanese soldiers sometimes behaved kindly and gentlemanly to local people. For example, Private Upper Class Makihara Nobuo witnessed one Japanese army medic treating a Chinese civilian who had mistakenly exploded a firecracker in his hand. On the following day Makihara paid villagers to purchase some food – instead of simply taking it –- after a lengthy negotiation. Makihara described these episodes in his diary on November 4 and 5, 1937 –- that is, one month before the start of the Nanking campaign. Private Saito Jiro of the 13th Division's 65th Regiment said that he provided some extra rations to the local people who had lost their houses to fire ...

Yamamoto, page 142:

Hanekura also described Chinese PoWs fighting each other for scarce rice in their captivity, even for what was spilled onto the ground. Another soldier of 65th Regiment, which had reportedly taken some 17,000 prisoners, reported that captives had gone to eating grass while their Japanese captors were at a loss to how to feed them. This sounds comparable to the desperation of large numbers of Soviet PoWs captured early in the German invasion of Russia.... The second immediate cause attributable to the Japanese side was the food problem. The forced march from Shanghai to Nanking made the Japanese dependent on robbery-like requisition for the food provisions and caused a continual food shortage. One can easily imagine how difficult it might be for troops, who had trouble feeding themselves, to allot food to PoWs. According to Major Sakakibara Kasue, a {South Expeditionary Force, or SEF] staff officer, the SEF made available one food ration for PoWs out of every five rations given to the Japanese soldiers. Provisions were so scarce that the prisoners interned within the city walls suffered from hunger. Hanekura Shoro, who was a squad commander of the 16th Division's engineer regiment, noted a rumor that the hunger was so acute that some prisoners had even committed suicide by hanging themselves ...

At the brigade level:

Emphasis of ammunition over food is comparable to that of the Soviets, who also took local grain supplies to feed their forces as they drove the Germans back westward. The one big difference was fuel for the strongly mechanized Soviet field armies.... Major General Sasaki of the 16th Division's 30th Brigade said in his diary entry of December 13: “We have not even one grain of rice. Although we can probably find some within the city walls, we cannot spare any food to prisoners.”

===================================

How might Japanese plans to feed their troops in the Philippines or Malaya campaigns have differed from those told here in central China?

In China the IJA took over civilian food supplies along the way. Against western forces, military provisions were captured during the advance, but the IJA would not have planned to rely on them as it had civilian foodstuffs in China?

We have seen a few photos of IJA field messing in the Philippines such as this, and possible others. But I myself have seen only one written mention of it. Here a prisoner of war from Bataan saw Japanese field cooks at work:

But they were not, and the prisoners were ordered onward to resume their march.At dawn of the second day … we passed a Jap non-commissioned officer who was eating meat and rice. "Pretty soon you eat," he told us.

… We were marched into the courtyard of a large prison-like structure, dating to the Spanish days, and told we would

eat, then spend the night there.

At one side of the yard food was bubbling in great caldrons. Rice and soy sauce were boiling together [as] kitchen corpsmen were opening dozens of cans and dumping Vienna sausage into the savory mess. The aromatic steam that drifted over from those pots had us almost crazy. While we waited we were given a little water. We imagined the rice and sausages were for us ...

- Dyess, Edward, Lt. Col. Excerpted from Don Congdon (ed.) Combat: the Pacific Theater (Dell. 1958), pages 44-45

- Morton, Lewis. The Fall of the Philippines (Center for Military History), page 375

- In our continuing thread about it, Taki explained the integration of captured enemy weapons and vehicles into IJA use. Captured rations and other foodstuffs would seem no different.

However, rice must be covered during cooking, and soy sauce is not added to it then. More probably fried rice was being cooked -- seasoned with the shoyu, Vienna sausages, and whatever else.

–- Alan

Re: Food rations in the Japanese forces

From ebay,seller tradereast5gev

- Sewer King

- Member

- Posts: 1711

- Joined: 18 Feb 2004, 05:35

- Location: northern Virginia

Re: Food rations in the Japanese forces

Thanks as always Peter.

At bottom left are a metal stockpot, probably an enameled metal bowl, and -- possibly -- a large square can of cooking oil, sat upon by the man at left.

====================================

Further mention of IJA provisioning in the Philippines invasion tells many difficulties late in the campaign. Continued from:

Morton, page 412:

Another mention echoes that of food shortage quoted earlier from some Japanese officers in central China:

In general, were supply plans for the Philippines made small in expectation of quick victory? This reason for shortage has been said of other Japanese offensives, but I have not seen it applied here.

–- Alan

As happens with many mess and kitchen photos, we can't easily see what's for dinner. Do these men have a circular steamer rack? since it does not look like a pan and shows no handles.Peter H wrote:From ebay,seller tradereast5gev: (Cooking detail?)

At bottom left are a metal stockpot, probably an enameled metal bowl, and -- possibly -- a large square can of cooking oil, sat upon by the man at left.

====================================

Further mention of IJA provisioning in the Philippines invasion tells many difficulties late in the campaign. Continued from:

- Morton, Lewis. The Fall of the Philippines, volume in the “Green Book” series “United States Army in World War II” (US Army Office of the Chief of Military History, 1953), pages 317 and 340

By the end of January, the 20th Infantry had largely been decimated. Having begun the Bataan campaign with 2690 men, only 650 remained by mid-February, with most of those wounded or sick. (page 345)Morioka's first efforts to comply with Homma's orders were limited to attempts to drop rations, medicine, and supplies from the air to his beleaguered forces on the beaches. But the Japanese aircraft were unable to locate their own troops in the jungle. Supplies fell as often on Americans and Filipinos as it did the starved Japanese. The [Philippine] Scouts of the 45th Infantry one day picked up twelve parachute packages containing food, medicine, ammunition, and maps. The rations consisted of a soluble pressed rice cake, sugar, a soy bean cake, a pink tablet with a strong salty taste, and “other ingredients [which] could not be identified.”

… The position of the Japanese in the Battle of the Pockets was not an enviable one. Since 31 January, when [Philippine Army] 1st Division troops had shut the gate behind them, Colonel Yoshioka [Yorimasa's 20th Infantry Regiment] had been cut off from their source of supply. Though they had successfully resisted every effort to drive them out, and had even expanded the original Big Pocket westward, their plight was serious. Without food and ammunition they were doomed. General Morioka attempted to drop supplies to them, but, as had happened during the Battle of the Points, most of the parachute packs fell into the hands of the Americans and Filipinos, who were grateful for the unexpected additions to their slim rations.

Morton, page 412:

Among the foods airdropped by the Japanese, I suspect that the pink tablets with “a strong, salty taste” were vitamin pills or supplements.Even by Japanese standards the lot of the [IJA] soldier on Bataan was not an enviable one [either]. Certainly he was not well fed. During January 14th Army's supply of rice had run low and efforts to procure more from Tokyo and from local sources in the Philippines had proved unavailing. As a result the ration had been drastically reduced in mid-February. Instead of the 62 ounces normally issued to the troops of Japan, the men on Bataan received only about 23 ounces, plus small amounts of vegetables, meat, and fish which were distributed from time to time. To this they added whatever they could buy, steal, or force from an unwilling civilian populace.

- (cf. USA vs. Homma, pages 2536, 2876-79, 2848, 3122, testimony of Homma and of Col. Horiguchi Shusuke, 14th Army surgeon)

Another mention echoes that of food shortage quoted earlier from some Japanese officers in central China:

... One of Homma's commanders, for example, sent an officer to the commander of a neighboring unit with the message, "Our regiment has been out of rations for six days. I have come to take back supplies." To this, the neighboring commander replied, "We have no food either. This morning I gnawed half a piece of bread. All I can give is six plugs of tobacco."

- (Taylor, Lawrence. A Trial of Generals (Icarus Press, 1981), page 68 but not sourced)

- 16th Division seems to have a hard time in these histories. Originally from Kyoto area, it had fought in central China among the forces at Nanking cited earlier. Besides its 20th Infantry suffering high losses, some others of its men were among those taken prisoner by the Fil-Am forces in the Battle of the Points.

According to General Homma, the 16th “did not have a very good reputation … for its fighting qualities.” (USA vs. Homma, p. 3057) Attempts to resupply it by airdrop in Bataan sound like those told in China. What unit (with what planes) would have made the airdrop?

In general, were supply plans for the Philippines made small in expectation of quick victory? This reason for shortage has been said of other Japanese offensives, but I have not seen it applied here.

- Or, were more provisions expected to be found in the Philippines than there were? It was said above that more rice was not forthcoming from Tokyo (maybe this meant Imperial GHO?).

It must have been difficult for Homma to ask for more supplies, since GHQ was displeased with 14th Army for the long delay of final victory at Bataan. Troop replacements and reinforcements was sent to him by early March, but several of Homma's staff were ordered to be replaced –- including his chief of supply.

–- Alan