What If-Finland had been prepared for the Winter War?

Re: What If - Finland had been prepared for the Winter War?

Looking forward what is your solution to great service chambering debacle in this what if.

7.62x54R (53R) all the way, as Finns decided historically, to initial disappointment "sport shooter" -faction of the armed forces, or going Mauser way. Your Finland has more money.

Regards

7.62x54R (53R) all the way, as Finns decided historically, to initial disappointment "sport shooter" -faction of the armed forces, or going Mauser way. Your Finland has more money.

Regards

- John Hilly

- Member

- Posts: 2618

- Joined: 26 Jan 2010, 10:33

- Location: Tampere, Finland, EU

Re: What If - Finland had been prepared for the Winter War?

Nowadays it is natural to call them "taistelusukeltaja", but when I was young they were really called "Sammakkomiehet" - "Frogmen".Mark V wrote:Combat frogmen ? I guess taistelusukeltaja, which means in english literally - combat diver.

So how about "Combat Frogs"? (I've no idea how this sounds to a native English-speaker)

Greets

Juha-Pekka

"Die Blechtrommel trommelt noch!"

Re: What If - Finland had been prepared for the Winter War?

Jep, but the open circuit diving equipment was developed only during occupation years in France. To my understanding before that popularization of diving with light gear of Cousteau, the word "frogman" was unknown.John Hilly wrote:Nowadays it is natural to call them "taistelusukeltaja", but when I was young they were really called "Sammakkomiehet" - "Frogmen".Mark V wrote:Combat frogmen ? I guess taistelusukeltaja, which means in english literally - combat diver.

So how about "Combat Frogs"? (I've no idea how this sounds to a native English-speaker)

Greets

Juha-Pekka

Word sukeltaja - diver -on the other hand encompasses about all human activity underwater in finnish and english - heavy or light equipment, independent air supply or not - and was term known then and now.

Regards

Re: What If - Finland had been prepared for the Winter War?

I'll be sticking with the historical 7.62x54R (53R) round, but I'll also rehash the whole debate for those not familiar with it as well as the reasoning for staying with the 7.62x54R in this scenario. It was quite interesting - but in this scenario, the "sports-shooters" get the short end of the stick. Combat-shooting all the way......Mark V wrote:Looking forward what is your solution to great service chambering debacle in this what if.

7.62x54R (53R) all the way, as Finns decided historically, to initial disappointment "sport shooter" -faction of the armed forces, or going Mauser way. Your Finland has more money.

Regards

Cheers..........Nigel

ex Ngāti Tumatauenga ("Tribe of the Maori War God") aka the New Zealand Army

Re: What If - Finland had been prepared for the Winter War?

... second thought:

For divers operating near surface, with light equipment, for operations like infiltrating enemy coastline for recce operations they may have used word uimari - swimmer.

taistelu-uimari - combat swimmer

For divers operating near surface, with light equipment, for operations like infiltrating enemy coastline for recce operations they may have used word uimari - swimmer.

taistelu-uimari - combat swimmer

Re: What If - Finland had been prepared for the Winter War?

Thx for the suggestions, I'll have to "dive" into this question a bit more.Mark V wrote:Jep, but the open circuit diving equipment was developed only during occupation years in France. To my understanding before that popularization of diving with light gear of Cousteau, the word "frogman" was unknown.John Hilly wrote:Nowadays it is natural to call them "taistelusukeltaja", but when I was young they were really called "Sammakkomiehet" - "Frogmen".Mark V wrote:Combat frogmen ? I guess taistelusukeltaja, which means in english literally - combat diver.

So how about "Combat Frogs"? (I've no idea how this sounds to a native English-speaker)

Greets

Juha-Pekka

Word sukeltaja - diver -on the other hand encompasses about all human activity underwater in finnish and english - heavy or light equipment, independent air supply or not - and was term known then and now.

Regards

Open circuit is out - that was really developed during the war and military divers generally used close circuit anyhow - no bubbles! Dry suits - I have to get into the diving suits and equipment used as well as the the whole "Diving in the Baltic Sea" issue as well. What I may end up doing here is posting a draft and then looking for suggestions before doing the "final" version. Have a couple of books on Decimas Mas to read first too.....should be interesting!

I do like "Combat Frogs" - that's a good one. Again, time to dive into the "Frogman" term and see where and when it emerged and if I can realistically use it. Otherwise Combat Diver is probably the best choice. Combat Swimmer might be a good one tho - that was what some of the other early units basically did. The British SBS in WW2 were more Swimmer-Canoeists than Divers. Likewise the US beach recce teams. Have a few books on them too - time to do some serious background research.

Kiitos........Nigel

ex Ngāti Tumatauenga ("Tribe of the Maori War God") aka the New Zealand Army

Finnish Coastal Defences of the 1930’s

OK, I'm going to jump ahead of myself here. I was intending to finish off the section on Coastal Defences before I posted this, but this section is finished so I'm going to post it, then return to complete the intervening sections on Coastal Artillery, which may take a while to get done.

Part IV - Finnish Coastal Defences of the 1930’s

While the Coastal Defence Divisions and Coastal Artillery Batteries and fortresses were focused on the defence of the coastline against any attempt at seaborne invasion, another outcome of the 1931 Military Review was the identification of the need for an offensive capability in the seas and on the islands surrounding Finland, particularly along the shore and archipelagoes of the Gulf of Finland. This capability should be not just defensive, but capable of taking the tactical initiative and attacking the enemy anywhere along the Baltic littoral, but with an emphasis on the Gulf of Finland. The decision was made that an elite Division, the Marine Jaegers (Rannikkojääkärit) would be formed to fufill this need and that this Division would be part of the Suomen Merivoimat (Navy) rather than the Army. Also anticipating potential command and control disputes, the decision was also made that the Marine Jaeger Division would have it’s own integrated Air Arm dedicated to close support and protection of the Marine Jaeger Division in combat.

The Marine Jaeger Division

Established in late 1934 by a direct order of Marshal Mannerheim’s, the Finnish Marine Jaegers (Rannikkojääkärit) were formed as the elite marine infantry arm of the Finnish Navy. Their insignia was the head of a sea-eagle in gold.The objectives of the Rannikkojääkärit were laid out as being:

(1) To conduct counter attacks against enemy landings in the Finnish archipelago, an environment known for its many small islands and skerries,

(2) To carry out raiding attacks from the sea on enemy held positions and

(3) To carry out full-scale attacks from the sea in support of Army operations.

(4) Anticipating that the Gulf of Finland may become completely frozen over, allowing flanking attacks by the enemy across the Ice, to prepare for and be capable of fighting major defensive actions on the Ice while at the same time being capable of taking the tactical offensive against the enemy;

An additional Battalion-sized unit Rannikkojääkärit formation (separate from the Marine Division itself) was to be trained as an elite unit for unconventional warfare, beach and coastline reconnaisance and reconnaissance behind enemy lines. This unit was also tasked with developing the capability to operate in and from the many lakes and swamps of Finland, and to train the Marine Division and Army units in these techniques. (A subsequent Post will examine this unit in

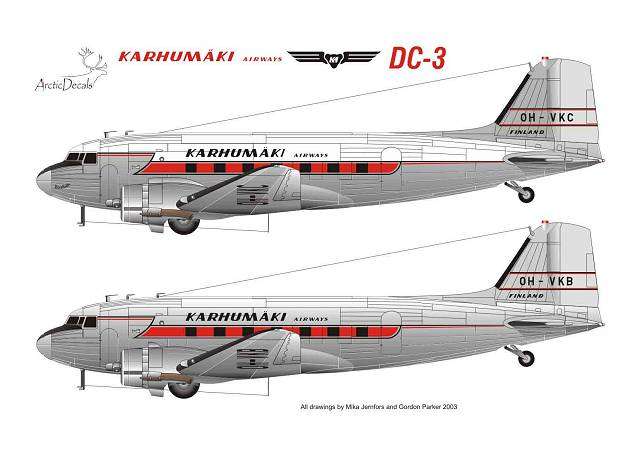

A small integrated Merivoimat Air Arm was formed up at the same time, with an allocated Table of Organisation of Two Fighter Squadrons, Two Dive Bomber Squadrons, One Reconnaisance Squadron and One Transport Squadron – although initially there were no aircraft or personnel. This would come later.

Selection and Training

While all Finnish males performed compulsory military service, only volunteers were accepted for the Rannikkojääkärit. The Division’s new training base was constructed at Nylands, near Ekenäs. After completion of the initial 6 months of Army Basic Training that all conscripts carrying out compulsory military service were required to complete, conscripts could voluntarily apply for service in the Rannikkojääkärit. Entry was by way of a tough 8 week selection course, with an emphasis on physical fitness, ability to operate in a maritime environment and cross-training. Interestingly, about 85% of volunteers passed the selection process – the Rannikkojääkärit Training Instructors were both tough and stubborn, and a strong emphasis was put on “encouraging” candidates who weren’t up to standard. Basically, it was a whole lot easier to get into the Rannikkojääkärit Selection Course than it was to get out of it, and over time the implacability of the Selection Course Instructors, and the pain and suffering experienced by candidates who were initially “below standard” became part of the Rannikkojääkärit “Myth.” Following the 8 week Selection Course, a further 4 months of specialized training was undertaken. Conscript volunteers were selected for NCO training during the initial 8 week Rannikkojääkärit Selection Course, while candidates for Rannikkojääkärit Officer Training were selected during the 8 week long Stage 1 of NCO training. About 10-20% of Stage 1 NCO candidates became officer candidates.

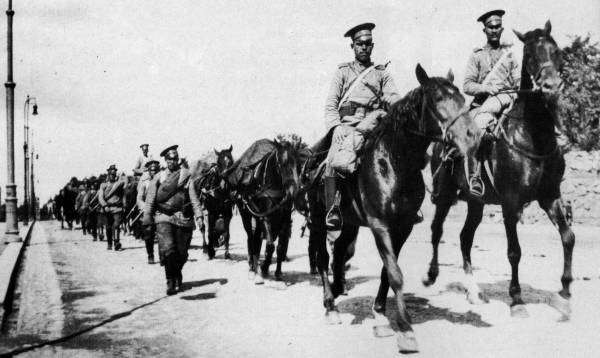

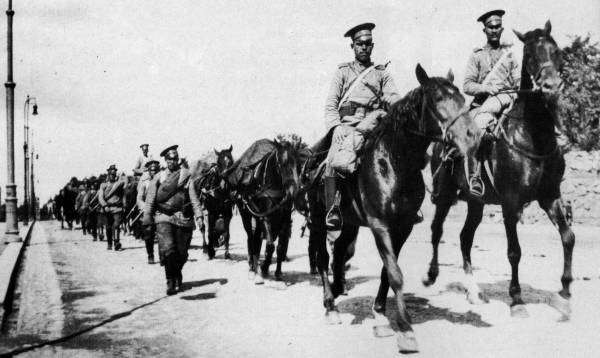

Rannikkojääkärit Trainees on Parade during Selection: Parades and Drill were not an important part of the Selection Course, but they did occur.

After completing the 6 months of Army Basic Training, it was expected that all volunteers for the Rannikkojääkärit were fit, capable of handling all army weapons and had all the basic military tactical skills. The first 4 weeks of the 8 week selection course therefore focused on achieving an increasingly higher level of physical fitness with a strong emphasis on endurance - for example, a Rannikkojääkärit candidate was more likely to spend his time marching with a heavy rucksack than doing push-ups. Marches were usually carried out with "full field equipment" (meaning 40-60kg depending on the task of the soldier) and could often be as long as 80-90km. The ability to operate in a maritime environment was also tested in this first stage. There was a very heavy emphasis on the development of military swimming skills, “drown proofing,” long distance swimming and small boat skills. Generally, conscripts who had completed the admittedly tough Army Basic Training thought they were pretty good. The Rannikkojääkärit Selection Course “gently” disabused them of this notion. It was pointed out from the first day that the Rannikkojääkärit were the elite, the best unit in the Finnish Military – and to be worthy of admittance, you had to be the absolute toughest and the best.

To this end, the Selection Course also emphasized the Finnish military's KKT unarmed combat system. Phsyical and mental aggression and the ability to deal with this was continuously developed, daily KKT sessions took place – these emphasized fear control (including methods of fear control and use of fear energy so as to master the “fight or flight” response and to eliminate inhibiting blocks to instant action in a crisis), encouraged a combat-ready mindset and “attack mindedness”, situational awareness, interactive tactics, attack mindedness, necessary ruthlessness, desensitization to inflicting injury, immunity to surprise or shock when and if injured oneself and so forth. And while the physical side of Selection was tough, most Rannikkojääkärit candidates found the mental part of the training most challenging. Not only were the physical requirements high, but candidates were required to learn and memorize a startling amount of information. Instructors went out of their way to put as much mental pressure on the soldiers as possible without actually breaking them and this was combined with high levels of sleep deprivation. The end result was that most candidates that failed selection, failed in these first four weeks. The second four weeks of Selection continued to emphasis physical endurance and maritime environment skills together with the main elements of Rannikkojääkärit training – maritime environment combat training and small unit tactical skills, weapons handling, tactical mobility and small boat operations. At the end of the 8 week Rannikkojääkärit Selection Course, candidates were subjected to a one week evolution which came to be termed “Paska Week” (‘Shit Week”). This was a one week period of continuous running, swimming, short tactical exercises, gym tests and small boat exercises with as little as 8 hours sleep over the one week period which was designed to test the candidates physical and mental endurance to the maximum.

After five days of this, the final two days of “Paska Week” involved a march of approximately 70km in length over which the Rannikkojääkärit candidates had to navigate themselves carrying 40-45kg of combat equipment. Every 5-10km the candidates were stopped to complete tasks given to them by instructors. Typical tasks were medical evacuation of "wounded" soldiers, shooting, weapons handling or map reading. At one point of the march candidates were put on a boat and transported to an unknown location from which they had to locate themselves on a map and find their way back to the route of the march. The remainder of the candidates who failed selection (usually a further 10-15%) usually failed in the first five days of Paska Week – the final two days were generally an endurance test – if you made it to the end of the two days and completed the march, you passed, although the candidates never knew this. At the end of the two day route march, candidates were told the evolution was over and they had passed selection. After a weekend recovery period, they were awarded the Rannikkojääkärit green beret with the golden sea eagle cap badge at a formal Passing Out Parade.

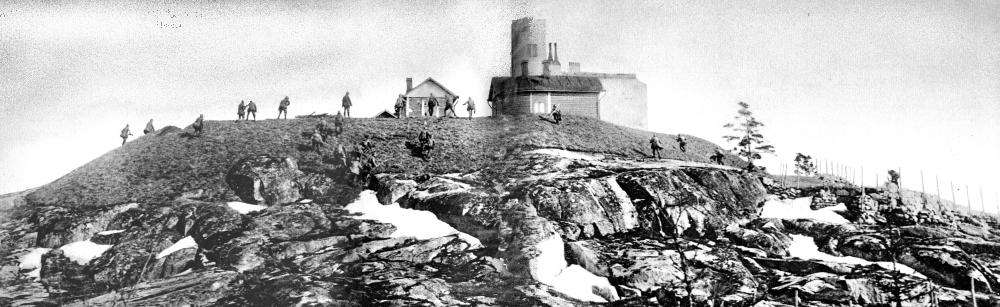

Exhausted looking Rannikkojääkärit Candidates at the end of the two-day Endurance Test – tired and sore, but still going. Note the folding boat to the right, used earlier on the exercise

Continuation Training then started. For soldiers, this consisted of a further 4 months where the emphasis was on developing and practicing marine warfare skills. Officers and NCO’s for these jääkärit were those who had completed Officer and NCO training from the previous intake. The training period for Officers and NCO’s was longer – they completed a six month Officer and NCO Training Course at the Amphibious Warfare School, which was considerably tougher and with a wide scope. This was then followed by a four month period commanding conscripts doing their Continuation Training. At all times during this period, Officers and NCO’s could fail – even in the last week of the four month Command and Leadership evolution – and the pressure was considerable. All in all, Rannikkojääkärit training was, along with Paratroop Jaeger training, the toughest given to any type of infantry in Finland. The results in the Winter War spoke for this.

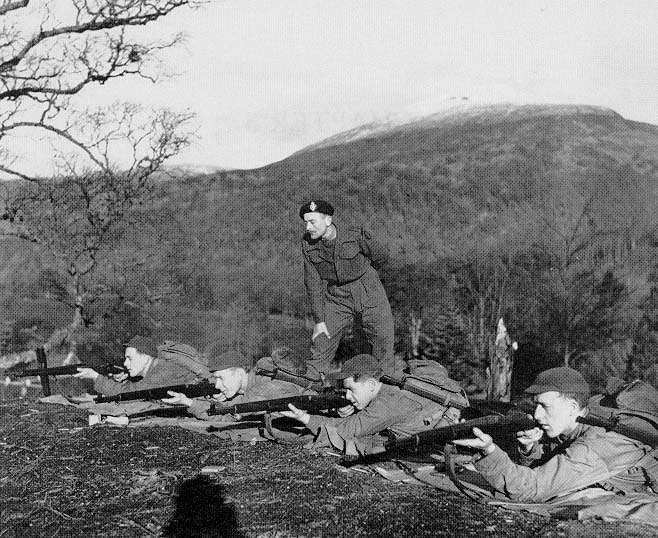

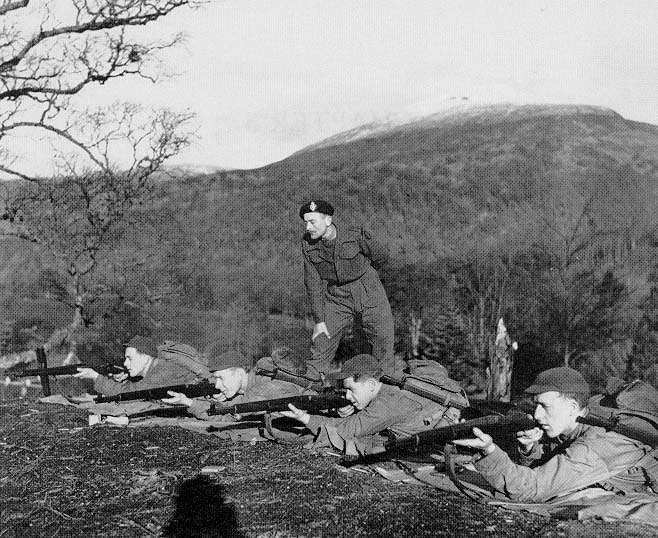

A Rannikkojääkärit Officer supervises a live-firing exercise in the field (note the Officer is wearing the Rannikkojääkärit Green Beret), Summer 1939

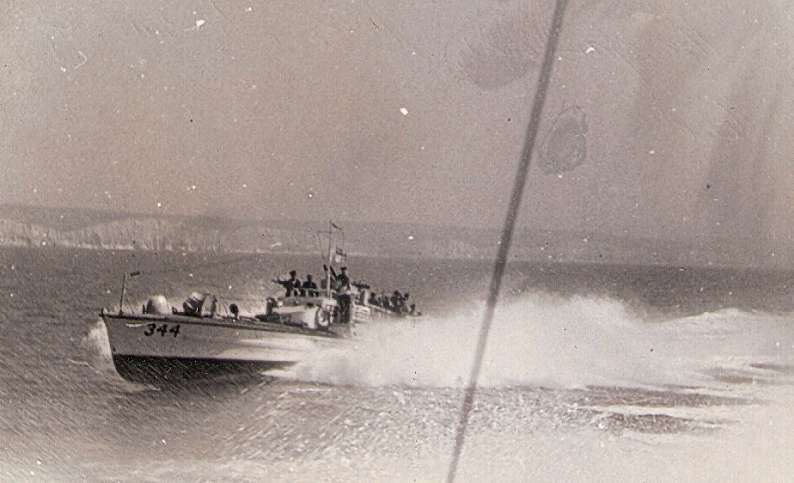

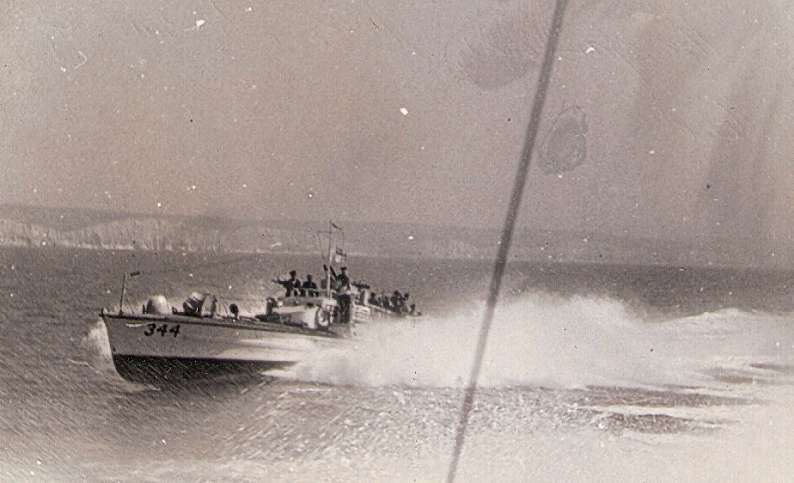

Rannikkojääkärit training came to include operations from the new Motor Torpedoe Boats and the even newer Fast Assault Boats that came into service in the late 1930’s

Rannikkojääkärit Training with Small Boats. Once volunteers passed Selection and entered Continuation Training, the emphasis was on the development of military combat skills and not on etiquette or the meeting of standards for uniforms – note the miscellaneous collection of clothing and headgear.

From 1936 on, Lotta volunteers were also accepted into the Rannikkojääkärit in support and non-combat positions. Female volunteers completed the same training as males, including KKT, but with a lower standard of physical strength and endurance set. Female volunteers were trained separately from males.

Female Rannikkojääkärit volunteers in training - 1937

Divisional Structure

(See US Marine Corps Report and Assessment of the Finnish Marine Division dated 1935 in section below).

Development of Doctrine

The major influence on the Rannikkojääkärit was the US Marine Corps. As mentioned earlier, in late 1931, Marshal Mannerheim had arranged for a number of Officers to be attached to the Marine elements of a number of countries – generally half a dozen officers to each country’s forces. These included the British Royal Marines, the US Marine Corps, the French Troupes Coloniales, the Italian San Marco Battalion, the Royal Netherlands Marine Corps and the Spanish Infantería Marina (lest you doubt, this unit enjoyed success during the Third Rif War in its innovative Alhucemas amphibious assault in 1925, when it employed coordinated air and naval gunfire to support the assault – in 1931 it was officially determined to be a "colonial force" by the Republicans and was denounced as “an instrument of imperialism”. It was sentenced to extinction by the Spanish republican government in 1931 but was still in existence in 1932 when the Finnish Officers were attached to it briefly. From all these various units, the Finns absorbed a wide range of techniques, skills and doctrine.

While many countries were reducing or eliminating their Marine forces in the aftermath of WWI, the US Marine Corps had established their reputation of ferocity and toughness in the battles on the Western Front, including Belleau Wood. Between the World Wars, the Marine Corps was headed from 1920-29 by Commandant John A. Lejeune and under his leadership, the Corps presciently studied and developed amphibious techniques that would be of great use in World War II. At the period the Finnish Officers were attached, the Commandant was Major General Ben H Fuller (1930-33) who was a strong advocate of the Marine Fleet Force concept – essentially, combined arms operations for the Marines. Fuller went out of his way to facilitate the education of the Finnish Officers and initiated an exchange program in 1933 whereby Finnish Officers were attached to the US Marine Corps while US Marine Corps Officers and experienced NCO’s were attached to the Finnish Rannikkojääkärit. The largest group of US Marine Corps Officers and NCO’s served with the Rannikkojääkärit over 1934 and 1935, greatly facilitating the initial establishment of the Rannikkojääkärit, the development of training programs and both strategic and tactical doctrine suited to the Finnish strategic and tactical environment. These officers, together with a small team of US Marine Corp pilots and aircrew who assisted with the Helldiver training, were influential in the development of the combined arms combat techniques and doctrine which were used to great effect in the Winter War and during Finland’s involvement in the Second World War.

1935 Report on the Finnish Marine Jaeger Division prepared for the US Marine Corps (Authored by US Marine Corps Major (deleted), commander of the US Marines Training Detachment on attachment in Finland)

ORGANIZATION AND TRAINING OF FINNISH MARINES

________________________________________

Origin.

In 1934, the Finnish Navy established a Marine Division and requested assistance from the US Marine Corps in establishing structure and organisation, strategic and tactical doctrine and in the establishment of training programs. The Finnish Marine Division is loosely based on the US Marine Divisional organisation, but is strongly influenced by the Finnish Army’s “Combined Arms Regimental Battle Group” structure. The Division is heavily combat-oriented and is structured with far less “tail” than a US Marine Corps Division.

As with all Finnish military units, the Marine Division is largely a Reservist Unit, with the greater part of the personnel being Reservists who have completed their training during their period of Conscript Service. Reservists generally participate in a limited number of weekend training days throughout the year, as well as a one to two week Annual Exercise which is usually carried out at the Battalion level. As of the time of writing this report, 3 Trainee Intakes have completed training and the Division is at approximately half-strength. The Finnish Commanding Officer (Marine Division) estimates that by 1938, the Division will have trained sufficient Marines to be able to operate at full Divisional strength in the event of mobilization.

Selection of Personnel.

Selection of initial Officer and NCO Cadre was made from a combination of appointments by the Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces and volunteers from Army Cadre. All other personnel are volunteers doing their compulsory Conscript Service and these fill almost all positions within the Division. Finnish Marine policy is that all trainees must have completed their six month Army Basic Training successfully, and must be volunteers. The first Intake of trainees commenced in 1934, from Volunteers who had just completed their six months of Army Basic Training and consisted of 2,500 men and 350 women.

(Of Note is that the Finnish Marines accept women volunteers for service in non-Frontline positions – generally, women soldiers fill all rear-area service, clerical, support and quartermaster/stores positions. Women complete the same training as male Marines including all-arms combat training – albeit with lower physical fitness standards. Of particular note is that this releases large numbers of male Marines for combat unit roles, something the Finns emphasized was important given their limited manpower. Also of note is that ALL women Marines are always armed with personal weapons and are trained in their use).

Missions.

The primary mission of the Finnish Marines is to take the tactical offensive in counter-attacking any attempted enemy attacks along the Finnish coastline and archipelagoes or in winter, across the frozen sea-ice of the Gulf of Finland. Secondary roles are Raiding attacks on the enemy and the support of Army operations. The objectives of the Finnish Marines were stablished as being:

(1) To conduct counter attacks against enemy landings in the Finnish archipelago, an environment known for its many small islands and skerries,

(2) To carry out raiding attacks from the sea on enemy held positions and

(3) To carry out full-scale attacks from the sea in support of Army operations.

(4) Anticipating that the Gulf of Finland may become completely frozen over, allowing flanking attacks by the enemy across the Ice, to prepare for and be capable of fighting major defensive actions on the Ice while at the same time being capable of taking the tactical offensive against the enemy;

Organization.

The Marine Division functions under the Advisor for Combined Operations (A.C.O.). The A.C.O. acts in an advisory capacity to, and executes the orders of, the Commander-in-Chief of the Finnish Military (currently, Marshal Mannerheim). The staff of the A.C.O. consists of officers of the Maavoimat (Army), Merivoimat (Navy), Ilmavoimat (Air Force), and the Rannikkojääkärit (Marines). The Marine Division is commanded by a Major-General who has both an operational and an administrative staff. The Division, however, does not train, nor does it function normally as a Division, but as separate Regimental Battle Groups which are based in various parts of Finland. The Marine Division is entirely serviced by the Navy.

At this time, approximately 2,500 to 3,000 trainees undergo a six month training period, with two six-month Training Courses run in each year. At the end of the six month training period, Enlisted Marines have completed their compulsory period of military service and are released, at which time they move to “Reserve” status and are required to participate in a limited number of weekend training days together with a short Annual Camp. Current plans are to continue training at this level for the next two years, by which time the Division will have a sufficient number of trained Reservists to fully man the Division in the event of mobilization. At this stage, Marine Selection will become more stringent and selective, with the objective being to train replacement personnel on an ongoing basis.

There are no Direct Entry Officers in the Marines. Every Conscript enters as an Enlisted Man and completes six months of Army Basic Training. There are no exceptions to this requirement. Volunteers for the Marines then complete a two month Selection Course, during which potential Officers and NCO’s are marked by the Training Cadre. On successful completion of Selection, these Officer and NCO candidates are requested to volunteer for Officer and NCO Trainng, which requires 18 months of service overall rather than the 12 months completed by Enlisted Men. Men cannot apply for Officer and NCO Training – they must be selected by the Training Cadre based on their performance during Selection. Following completion of training, additional courses are available to Reservist Officers and NCO’s, who are all members of the Finnish Civil Guard, the Suojeluskuntas, which now has a “Marine” component to it.

The formal organisation of the Finnish Marine Division is as follows:

The Marine Division is made up of 3 Regimental Battle Groups with a Divisional HQ and a Training Wing attached to the Divisional HQ. Divisonal HQ is largely administrative and aside from logistical support and administration, is responsible for the Training of Marines, with approximately 2,500-3,000 volunteers in a Training Intake in any one six month period. Over 1934 and 1935, some 8,000 Marines have successfully completed training and are formed up into the 3 Regimental Battle Groups (currently these are all at approximately half strength. It is anticipated by the Divisional HQ that by year-end 1937, sufficient Marines will have been trained for all 3 Regimental Combat Groups to be up to strength on mobilization. In the event of mobilization, plans call for the current training Intake to be held back as “replacements” for casualties and for the next twelve months Intake Class to be called up and trained in one Intake, possibly to form a fourth Regimental Battle Group on completion of what would be “accelerated” training.

Regimental Battle Group

o Regimental HQ

- HQ

- Security Company

- Signals Company

- Recconaissance Company

- Pioneers Company (Engineers)

o Marine Strike Battalion I (Iskupataljoona – xxxx men)

o Marine Strike Battalion II (Iskupataljoona – xxxx men)

o Marine Strike Battalion II (Iskupataljoona – xxxx men)

o Heavy Weapons Battalion

- 2 x Field Artillery Battalions (12 Field Guns each, 24 in total)

- Anti-Aircraft Company (12 AA Guns)

- Mortar Company (12 x 81mm Mortars)

o Regimental Tail

- Supplies Company

- Ammunition Supply Company

- Transport Company

- Field Kitchen Company

- Field Hospital + Ambulance Platoon

- Vehicle Repair and Fuel Supply Unit

- Field Hospital for Horses

- Field Post Office

- Clothing Depot

Note that the Regimental Battle Group, as it is termed in Finnish military nomenclature, is a fully self-contained organisation with its own integral artillery battalions together with all necessary support, including logistics. Strategic assets are controlled at Corps or Military HQ level rather than subdivided down into Divisional assets.

Marine Strike Battalion (Iskupataljoona)

o Battalion HQ

- HQ

- Security Platoon

- Signals Platoon

- Recconaissance Platoon

o Strike Company I (Iskukomppania – 124 men)

o Strike Company II (Iskukomppania – 124 men)

o Strike Company III (Iskukomppania – 124 men)

o Support Company

- Mortar Platoon (4 x 81mm Mortars)

- Pioneer Platoon (Engineers)

- Anti-tank Platoon (4 x AT Guns)

- AA Gun Platoon (4 x AA Guns)

- Heavy Machinegun Platoon

o Logistics Company

- Transport Platoon

- Ammunition Supplies Platoon

- Supplies Platoon

- Boat Platoon

- Medical Platoon

- Battalion Admin Section

Marine boat transport varies as the Marine Division has no purpose-built boats (although planning has begun to acquire these, this is not expected to be completed in the short-term future). Marines are generallycarried to their destimation on Navy boats where these are available, otherwise civilian motor launches and fishing boats are used. Generally, each launch or boat is capable of transporting 1 to 2 sections of Marines and when I use, is fitted with a Maxim machinegun in the bow for fire support. The maximum speed of these boats is modest by military standards and the pace is usually set by the slowest boat of the group. Where motor boats are not available, rowing boats are used, and canoes are often used by the Reconnaissance Platoons.

While the TOE calls for large numbers of Mortars, Anti-tank Guns, AA Guns and Machineguns, these are generally not available. The Finnish Military have various acquisition programs underway and the apparent target is to have the TOE up to strength over as five year period. Much of the current strength in equipment is however only on paper.

Marine Strike Company ((Iskukomppania – 124 men)

o Company HQ (29 men)

- Company Commander

- Command Squad (6 man Sigs/Messenger Section, 4 man Sniper Section, 9 man AT Section)

- Supplies Section (1 Sgt, 7 men)

o Strike Platoon I (Iskukomppania – 32 men)

- Platoon Command Squad (1 Officer, 1 Sgt, 1 Sig, 2 Messengers, 1 Medic, 2 man Sniper Team)

- Rifle Squad I (Corporal, 2 man LMG Team, 2 SMG Men, 3 Riflemen)

- Rifle Squad II (8 men, as above)

- Rifle Squad III (8 men, as above)

o Strike Platoon II (Iskukomppania – 32 men)

o Strike Platoon III (Iskukomppania – 32 men)

Strike Companies are generally heavy on automatic firepower, with provision in the TOE for numerous light machineguns and submachineguns. The Marines also put a heavy emphasis on the use of Snipers (6 x 2 man Sniper Teams within the Company strength of 124 men). Provision is also made for 4 x 2 man Anti-Tank Rifle Teams under the control of the Company Command Squad, although at this time it should be noted that Anti-Tank Rifles are not available). The Marines also put a great deal of emphasis on Signals and communications. Plans are apparently underway for units down to the Platoon-level to be equipped with Radios at some stage (these are apparently under development in a secret project, details of which were not divulged – at present Field Telephones and Messengers are used). There is one Medic in each Platoon Command Squad and usually at least one man in each Section has also completed Medic Training. All Marines are expected to qualify as Expert Marksman, and Sniper Training is encouraged. Also noted was that the standard Section strength of 8 men is exactly suitable for embarking in the small Dory-type boats that the Marines use in training.

Weapons.

Although the establishment (Tables of Organization) provides a definite allowance and allocation of weapons, neither the numbers of weapons nor their distribution is rigidly adhered to. In every case the distribution of weapons is made according to the tactical requirements of the particular mission to be performed. Each Regimental Battle Group has a separate store of extra weapons and thus extreme flexibility in armament is assured. A typical store contains:

Maxim Machineguns; Suomi Submachineguns; 81mm mortars and a supply of both smoke and HE shell for each; defensive (fragmentation) hand grenades; smoke pots; Flare pistols; knuckle dusters; explosives for demolitions of all types.

Normally each Platoon is allocated one Maxim machinegun and one Suomi submachinegun per section. The allocation of the 81mm mortars is left entirely to the Commander who employs them according to the requirements of the situation. As indicated above, additional weapons are available in stores and may be assigned. The important point to note is the extreme flexibility in armament and the degree of initiative permitted Platoon and Company leaders in its distribution.

Clothing and Equipment.

Clothing and equipment furnished Marines includes a variety of types thus permitting flexibility in dress and battle equipment. Normal clothing is "battle dress," a two piece woolen garment, stout boots and anklets (short leggings). In colder weather a sleeveless button-up leather jacket which reaches the hips is worn over or under battle dress. A two piece waterproofed denim dungaree-type coverall is also provided for wear over battle dress in damp or rainy weather. In addition to the ordinary hobnailed boots, a rubber soled shoe and a rope soled shoe are provided for missions that require stealthy movements over paved roads, through village streets, for cliff climbing, and so forth. A heavy ribbed wool jersey with long sleeves and turtle neck and a wool undervest and woolen hat and gloves are also available for cold weather wear. Overcoats may be worn at any time during training or operations in severe weather. A white “snowsuit” overall is worn during winter operations for concealment against snow or ice. All clothing is designed and worn with the sole purpose in view of comfort and utility under actual operating conditions. There are no specific uniform requirements for operations – again, this is at the discretion of the unit commander. No leather belts are worn either by officers or enlisted men. A fabric waist belt is provided for wear when deemed appropriate. Finnish Marines cold-weather clothing is highly effective and well-suited to the climatic extremes of the Finnish Winter. Marines are allowed to wear their own winter clothing beneath uniforms in Winter weather, with no requirement for uniformity. While the Marines look what we would term as “sloppy”, this in no way impairs their fighting effectiveness or unit and combat discipline, which is exemplary.

Basically, every officer and man is provided with standard army field equipment similar to our own but this may be augmented or discarded as needed. In addition, certain special equipment is available in Marine stores and is issued to individuals or troops as the occasion requires. Principal items are listed below:

Fighting knife; Individual cooker; Compass; Field rations; skiis and poles; individual life belt; Primus stoves; one gallon thermal food containers; gas cape; wristlets; 2 man rubber boat; plywood (sectionalized) canoe; collapsible canvas canoe; bamboo and canvas stretchers; 2" scaling ropes; 1" mesh heavy wire (6' x 24") in rolls for crossing entanglements (see under "Training"); Toggle ropes (see under "Training"); Transportation equipment for Reserve units (administrative) is generally civilian and the personal property of Reservists;

Communication equipment: Radio sets (portable voice and key type, weight 36 lbs, voice range 5 miles), Semaphore flags, Blinker guns, Flare pistols and flares.

Training.

Marine training is conducted along the following lines:

It seeks the development of a high degree of stamina and endurance under any operating conditions and in all types of climate.

It seeks to perfect all individuals in every basic military requirement as well as in special work likely to be encountered in operations viz: swimming, boatwork, wall climbing, skiing and so forth.

It aims to develop a high percentage of men with particular qualifications, viz: motorcyclists, truck drivers, small boat operators, marine engine engineers, etc.

It aims to develop self confidence, initiative and ingenuity in the individual and in the group.

It seeks to develop perfect team work in operating and combat.

All men volunteering for service in the Marines are personally interviewed by an officer.

In its training the Marine Division is prepared to accept casualties in training rather than to suffer 50% or higher battle casualties because of inexperienced personnel. All training is conducted with the utmost reality and to the end that the offensive spirit is highly developed. Wide latitude is accorded commanders in the training methods employed, and thus the development of initiative, enterprise, and ingenuity in the solution of battle problems, and the development of new techniques is encouraged. A corresponding latitude is accorded unit commanders. Only the highest standards are acceptable and if officers and men are unable to attain them, they are returned to the Army immediately. Leaves are accorded Marine personnel during prolonged training periods in order to prevent men "going stale."

An appreciation of the type of training conducted by Marines may be arrived at by brief descriptions of observed routine training executed by five different Marine Training Companies over a period of five days.

Assault Course.

All obstacle assault courses are not the same but vary in accordance with terrain and are generally constructed from whatever materials are available locally.

Swimming.

All Marines are taught to swim, and lengthy sea-swims are a common occurrence – daily during Selection and at least twice a week during what the Finns call “Continuation Training.” Sea-swims of ten miles are not uncommon.

Cliff and Rock Climbing.

Marines receive special training in cliff and rock climbing and Marines are sent from time to time to appropriate regions for practice.

Demolitions.

A general course is given to all members of the Marines in demolitions and more detailed instructions are given to a demolition group within each Company. These specially trained groups are taught demolition as affecting bridges, rail installations, machinery, oil tanks, etc. They are taught how to crater and to blow buildings to provide temporary road blocks. At xxx on December 3 1934, during the course of a night problem (attack on a village), in which three Platoons participated, the following demolitions were employed: Explsove torpedoes for gapping wire, booby traps installed in likely avenues of approach, and well camouflaged piano trip wires set to explode land mines. The explosive torpedoes were real enough but booby traps and land mines were represented by detonators. Very few booby traps were exploded as men kept their wits about them and their eyes open. Sufficient training allowance of all types of high explosives, fuzes, and detonators is made available so that this important training is continuous. TNT amd Nitro-starch are employed as explosives.

Street Fighting.

House to house street fighting is extensively practiced.

Unarmed Combat and Combat with Knives and Hand Weapons

The Finnish Military has evolved a specialized technique of hand-to-hand combat they call KKT. KKT utilizes a variety of fighting techniques together with the use of knives, machetes, entrenching tools and any other item that can be used as a weapon. The technique emphasizes an aggressive mindset and the ability to keep on fighting even if injured. Finnish Marines generally participate in lengthy KKT sessions on a daily basis, even when in the Field, and KKT techniques such as sentry removal are regularly practiced. It seems a highly effective fighting technique.

Field Combat Firings.

Both day and night field firings were observed. In one night firing exercise, a Platoon fired on low silhouette targets at a range of about 150 yards. The terrain was rolling countryside. A light rain was falling. Illumination was provided by flares fired from the flank. It was attempted to keep the flares 50 yards in front of the targets. Machine gunners posted on the flanks of each subsection fired with the subsection. Approximately 80% hits were scored out of an average 170 rounds fired per section.

Much time is devoted to tactical problems ("schemes") in which live ammunition is fired by all weapons. The strikingly effective use of smoke in assault at night was shown.

Marches.

On December 5, 1934, one Platoon of Marines executed a forced march of fourteen miles in two hours. Equipment: combat packs and rifles, uniform: battledress and steel helmets. This march took place along a macadam road through rolling countryside. The weather was chilly with light snow.

Obstacles.

On December 3, and December 5 1934, different Platoons were observed crossing barbed wire obstacles. Training and overcoming obstacles include:

1. Action against triple concertina.

2. Action against double-apron fence.

(In attacking any type of wire fastened securely to screw pickets, the pickets themselves on each side of the bay of wire to be crossed are seized by the leading men and bent to the ground, thus materially aiding in the wire-crossing.)

3. Use of Explsove Torpedoes

Wall-Scaling.

1. Walls 10 - 12 feet high.

2. Walls 20 feet high.

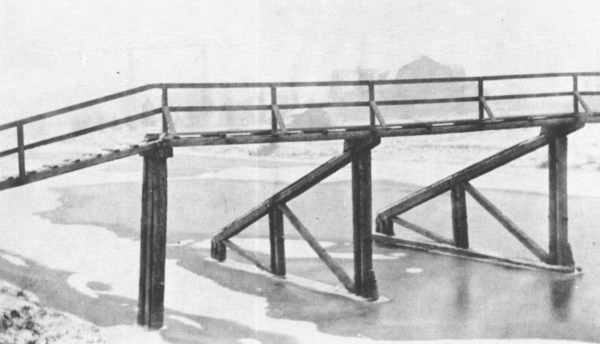

Stream Crossings.

Stealth and initiative in field operations.

Platoon and Section operational methods of infiltration.

Discipline and Morale.

To all appearances the discipline and morale of Marines is exceptionally high. This may be in large measure accounted for by the fact that all Marine personnel are selected volunteers who applied for this type of duty because of the prospects of more challenging training and the “image” of the Marines as more action-oriented and with less emphasis on Drill and Regulations than the Army.

In talks with officers and senior NCO’s we gained the impression that unit discipline is largely self imposed and that the application of disciplinary measures by commanders is a rare necessity. Respect for rank is observed but there is no saluting or standing to attention when enlisted men talk to Officers or NCO’s or when giving or receiving orders. No rank identification is worn in the field or at any time except on formal Parades and Officers, NCO’s and Enlisted Men dress and are equipped completely identically (to the extent that Officers carry Rifles or SMG’s – and almost all personnel are equipped with a Pistol as a “reserve” weapon in additiona to their standard Rifle or SMG). Officers and NCO’s are expected to know their men individually and to lead from the front or by example at all times. Marine Officer and NCO training emphasizes the “Follow Me” rather than the “Do this or that” approach.

An excellent spirit of fellowship prevails between officers, NCO’s and enlisted men and is evident in all training and exercises. Officers and NCO’s participate in all exercises with the men and two half days a week are set aside for sports. All are required to take part in one form or another.

Officers, NCO’s and enlisted men in training live on base or in the field, with a large amount of time spent in the field on exercises. Contrary to the expectations of most officers the large amount of time spent in the field, when combined with generous weekend leave, has had a very positive effect on morale.

Undoubtedly the fact that commanders have the prerogative of immediately returning a man to the Army for breaches of discipline or inaptitude for Marine duties has an important effect in maintaining the existing high disciplinary level.

The varied and realistic nature of the training undertaken is likewise an aid to morale. Current events talks are given weekly by all Platoon commanders using material furnished by the ABCA (Army Bureau of Current Affairs). Outside speakers, (Naval, Army and Air Force Officers, Civilians, University Professors and so on) give regular talks on the larger aspects of the the military, economics, industry etc. and try to make these relevant to the Marines military objectives These all broaden the Marines' point of view and dispel boredom.

Frequent weekends are granted from Friday P.M. to Monday A.M., and liberal leave policy obtains. The men are not allowed to go stale in training.

Conclusions.

The Finnish Marines are evolving as an effective fighting force with high disciplinary standards and morale. Combat effectiveness is adjudged to be high and some of the innovative approaches taken (unarmed combat training, use of women in non-combat positions, high ratio of “fighters” to “tail”, flexibility in weapons and dress, variety of training) could well be examined in more detail with a view to possible adoption.

The Combined Arms Regimental Battle Group concept that the Finnish military is adopting is also worthy of further examination. The rationale behind this, as explained by the Finnish Commander-in-Chief, is that the Divisional structure is too complex, too large, centralizes too many capabilities at a high level, deploys too slowly, and is too vulnerable to attacks on centralized assets. The centralization of too many critical warfighting assets at the divisional level means that the the brigade force that emerges from this structure lacks cohesion as key assets such as artillery are under divisional control and not immediately available when needed, joint command and control slows the command decision-making process, communications and intelligence is at a divisional level and intelligence in particular is slow to filter down to the fighting units and the division itself is very slow to deploy.

The Finnish Military’s Combined Arms Regimental Battle Group is an all arms Combat Group of roughly 5,000 troops with embedded command, control, communications and intelligence as well as key supporting assets such as Artillery and Supply, the division and brigade echelons are compressed into one echelon that enables: (1) Integration with other services at a lower level than the traditional division; and, (2) far greater operational independence in smaller formations. This reorganized formation provides a far more agile and responsive force mix that is based on the way the Finnish military intends to fight rather than on “garrison” formations that make administration easier. The whole ethos of the Finnish Military is, as expressed by the C-in-C, “More Teeth, Less Tail!” The Regimental Battle Group organization is intended to eliminate "unnecessary" headquarters, place the necessary combat assets under one commander, streamline the logistics tail (and man as much as possible of the “tail” with women Marines) and move the personnel savings back to the units that actually deploy and fight.

The Finnish Combined Arms Regimental Battle Group is on the one hand larger than a traditional Brigade, but on the other hand smaller and more flexible than the traditional Division. In addition, a heavy emphasis in training is placed on the development of Combined Arms fighting techniques and skills. The Battle Group trains as one unit with all assets, and with a significant amount of cross training. Task Forces can be put together from a varying number of Regimental Battle Groups suited to the mission, and this is something the Finnish Military has begun to cover in Staff Training exercises. The Divisional HQ still exists, but as a logistical support and administration unit rather than as a Command and Control layer. It remains to be seen how this concept will work out in battle but it is certainly worthy of investigation on the part of the US Marine Corps.

End of Report. ..

Note: The author of this report, on his return to the US, made a number of attempts to have the US Marine Corps further study the Finnish Rregimental Battle Group concept but was either ignored or overruled. As the world would discover in 1940 when Germany's Armored Battle-groups overran France, the full impact of the new technology in war was achieved after the German Army changed the way their armored armed forces were organized, trained, led and employed in action together with other air and ground elements – and only at this stage did the world begin to understand the new concepts – and at that, only slowly.

That this Combined Arms Battlegroup concept was first successfully employed by the Finnish Military, and with far more devastating effect than the Germans, was something that passed the rest of the world by. The sole exception was Germany, large due to the beating they took from the Finnish Military in Norway – the first defeat the Germans suffered in WW2 and again, one that the rest of the world missed due to the debacle in France. The British Army, units of which fought alongside the Finns in Norway, had the opportunity to learn, but again, in the aftermath of Dunkirk and then the turmoil in North Africa, missed this opportunity, as they would miss so many other lessons that could have been learnt from the Winter War.

Winter War.

In the early days, improvisation was the name of the game....

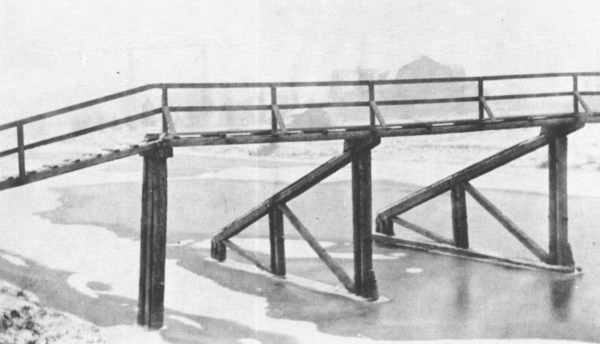

A civilian launch being used on a Marine Reservist training weekend exercise - Summer 1936

On exercise on Lake Laatoka, 1937

The Marine Jaegers new Fast Assault Boat was introduced in mid-1938 and was derived from the Motor Torpedo Boats designed and starting to come into service from the mid-1930's. Capable of carrying two sections (16 men), 2 of these fast boats could carry a Platoon at a maximum speed of 35 knots. Some 35 of these Boats were in service at the time of the Winter War. They proved useful in rushing reinforcements to islands that came under Soviet attack early in the Winter War, capable of moving the best part of half a Battalion in one movement. The Fast Assault Boat was designed for the Marine Jaegers by the american boat designer and manufacturer, Andrew Higgins, with whom the Merivoimat had developed a close relationship while finalizing the design of their Motor Torpedo Boats and Fast Minelayers. In the end, these Fast Assault Boats would prove more useful in fighting the Germans in 1944 and 1945

So, just put the blinkers on and pretend to yourself this is a filmclip of a training exercise from 1939!!! (Sorry, best I can do)

Rannikkojääkärit boarding Suomen Merivoimat Higgins-Class Assault Landing Craft in mid-1944 shortly before the amphibious assault into East Prussia which cut off the German forces still fighting in Lithuania. At this stage of the war, the Finnish entry on the Allied side had resulted in the supply to Finland of large quantities of American equipment – in marked contrast to the period of the Winter War.

Part IV - Finnish Coastal Defences of the 1930’s

While the Coastal Defence Divisions and Coastal Artillery Batteries and fortresses were focused on the defence of the coastline against any attempt at seaborne invasion, another outcome of the 1931 Military Review was the identification of the need for an offensive capability in the seas and on the islands surrounding Finland, particularly along the shore and archipelagoes of the Gulf of Finland. This capability should be not just defensive, but capable of taking the tactical initiative and attacking the enemy anywhere along the Baltic littoral, but with an emphasis on the Gulf of Finland. The decision was made that an elite Division, the Marine Jaegers (Rannikkojääkärit) would be formed to fufill this need and that this Division would be part of the Suomen Merivoimat (Navy) rather than the Army. Also anticipating potential command and control disputes, the decision was also made that the Marine Jaeger Division would have it’s own integrated Air Arm dedicated to close support and protection of the Marine Jaeger Division in combat.

The Marine Jaeger Division

Established in late 1934 by a direct order of Marshal Mannerheim’s, the Finnish Marine Jaegers (Rannikkojääkärit) were formed as the elite marine infantry arm of the Finnish Navy. Their insignia was the head of a sea-eagle in gold.The objectives of the Rannikkojääkärit were laid out as being:

(1) To conduct counter attacks against enemy landings in the Finnish archipelago, an environment known for its many small islands and skerries,

(2) To carry out raiding attacks from the sea on enemy held positions and

(3) To carry out full-scale attacks from the sea in support of Army operations.

(4) Anticipating that the Gulf of Finland may become completely frozen over, allowing flanking attacks by the enemy across the Ice, to prepare for and be capable of fighting major defensive actions on the Ice while at the same time being capable of taking the tactical offensive against the enemy;

An additional Battalion-sized unit Rannikkojääkärit formation (separate from the Marine Division itself) was to be trained as an elite unit for unconventional warfare, beach and coastline reconnaisance and reconnaissance behind enemy lines. This unit was also tasked with developing the capability to operate in and from the many lakes and swamps of Finland, and to train the Marine Division and Army units in these techniques. (A subsequent Post will examine this unit in

A small integrated Merivoimat Air Arm was formed up at the same time, with an allocated Table of Organisation of Two Fighter Squadrons, Two Dive Bomber Squadrons, One Reconnaisance Squadron and One Transport Squadron – although initially there were no aircraft or personnel. This would come later.

Selection and Training

While all Finnish males performed compulsory military service, only volunteers were accepted for the Rannikkojääkärit. The Division’s new training base was constructed at Nylands, near Ekenäs. After completion of the initial 6 months of Army Basic Training that all conscripts carrying out compulsory military service were required to complete, conscripts could voluntarily apply for service in the Rannikkojääkärit. Entry was by way of a tough 8 week selection course, with an emphasis on physical fitness, ability to operate in a maritime environment and cross-training. Interestingly, about 85% of volunteers passed the selection process – the Rannikkojääkärit Training Instructors were both tough and stubborn, and a strong emphasis was put on “encouraging” candidates who weren’t up to standard. Basically, it was a whole lot easier to get into the Rannikkojääkärit Selection Course than it was to get out of it, and over time the implacability of the Selection Course Instructors, and the pain and suffering experienced by candidates who were initially “below standard” became part of the Rannikkojääkärit “Myth.” Following the 8 week Selection Course, a further 4 months of specialized training was undertaken. Conscript volunteers were selected for NCO training during the initial 8 week Rannikkojääkärit Selection Course, while candidates for Rannikkojääkärit Officer Training were selected during the 8 week long Stage 1 of NCO training. About 10-20% of Stage 1 NCO candidates became officer candidates.

Rannikkojääkärit Trainees on Parade during Selection: Parades and Drill were not an important part of the Selection Course, but they did occur.

After completing the 6 months of Army Basic Training, it was expected that all volunteers for the Rannikkojääkärit were fit, capable of handling all army weapons and had all the basic military tactical skills. The first 4 weeks of the 8 week selection course therefore focused on achieving an increasingly higher level of physical fitness with a strong emphasis on endurance - for example, a Rannikkojääkärit candidate was more likely to spend his time marching with a heavy rucksack than doing push-ups. Marches were usually carried out with "full field equipment" (meaning 40-60kg depending on the task of the soldier) and could often be as long as 80-90km. The ability to operate in a maritime environment was also tested in this first stage. There was a very heavy emphasis on the development of military swimming skills, “drown proofing,” long distance swimming and small boat skills. Generally, conscripts who had completed the admittedly tough Army Basic Training thought they were pretty good. The Rannikkojääkärit Selection Course “gently” disabused them of this notion. It was pointed out from the first day that the Rannikkojääkärit were the elite, the best unit in the Finnish Military – and to be worthy of admittance, you had to be the absolute toughest and the best.

To this end, the Selection Course also emphasized the Finnish military's KKT unarmed combat system. Phsyical and mental aggression and the ability to deal with this was continuously developed, daily KKT sessions took place – these emphasized fear control (including methods of fear control and use of fear energy so as to master the “fight or flight” response and to eliminate inhibiting blocks to instant action in a crisis), encouraged a combat-ready mindset and “attack mindedness”, situational awareness, interactive tactics, attack mindedness, necessary ruthlessness, desensitization to inflicting injury, immunity to surprise or shock when and if injured oneself and so forth. And while the physical side of Selection was tough, most Rannikkojääkärit candidates found the mental part of the training most challenging. Not only were the physical requirements high, but candidates were required to learn and memorize a startling amount of information. Instructors went out of their way to put as much mental pressure on the soldiers as possible without actually breaking them and this was combined with high levels of sleep deprivation. The end result was that most candidates that failed selection, failed in these first four weeks. The second four weeks of Selection continued to emphasis physical endurance and maritime environment skills together with the main elements of Rannikkojääkärit training – maritime environment combat training and small unit tactical skills, weapons handling, tactical mobility and small boat operations. At the end of the 8 week Rannikkojääkärit Selection Course, candidates were subjected to a one week evolution which came to be termed “Paska Week” (‘Shit Week”). This was a one week period of continuous running, swimming, short tactical exercises, gym tests and small boat exercises with as little as 8 hours sleep over the one week period which was designed to test the candidates physical and mental endurance to the maximum.

After five days of this, the final two days of “Paska Week” involved a march of approximately 70km in length over which the Rannikkojääkärit candidates had to navigate themselves carrying 40-45kg of combat equipment. Every 5-10km the candidates were stopped to complete tasks given to them by instructors. Typical tasks were medical evacuation of "wounded" soldiers, shooting, weapons handling or map reading. At one point of the march candidates were put on a boat and transported to an unknown location from which they had to locate themselves on a map and find their way back to the route of the march. The remainder of the candidates who failed selection (usually a further 10-15%) usually failed in the first five days of Paska Week – the final two days were generally an endurance test – if you made it to the end of the two days and completed the march, you passed, although the candidates never knew this. At the end of the two day route march, candidates were told the evolution was over and they had passed selection. After a weekend recovery period, they were awarded the Rannikkojääkärit green beret with the golden sea eagle cap badge at a formal Passing Out Parade.

Exhausted looking Rannikkojääkärit Candidates at the end of the two-day Endurance Test – tired and sore, but still going. Note the folding boat to the right, used earlier on the exercise

Continuation Training then started. For soldiers, this consisted of a further 4 months where the emphasis was on developing and practicing marine warfare skills. Officers and NCO’s for these jääkärit were those who had completed Officer and NCO training from the previous intake. The training period for Officers and NCO’s was longer – they completed a six month Officer and NCO Training Course at the Amphibious Warfare School, which was considerably tougher and with a wide scope. This was then followed by a four month period commanding conscripts doing their Continuation Training. At all times during this period, Officers and NCO’s could fail – even in the last week of the four month Command and Leadership evolution – and the pressure was considerable. All in all, Rannikkojääkärit training was, along with Paratroop Jaeger training, the toughest given to any type of infantry in Finland. The results in the Winter War spoke for this.

A Rannikkojääkärit Officer supervises a live-firing exercise in the field (note the Officer is wearing the Rannikkojääkärit Green Beret), Summer 1939

Rannikkojääkärit training came to include operations from the new Motor Torpedoe Boats and the even newer Fast Assault Boats that came into service in the late 1930’s

Rannikkojääkärit Training with Small Boats. Once volunteers passed Selection and entered Continuation Training, the emphasis was on the development of military combat skills and not on etiquette or the meeting of standards for uniforms – note the miscellaneous collection of clothing and headgear.

From 1936 on, Lotta volunteers were also accepted into the Rannikkojääkärit in support and non-combat positions. Female volunteers completed the same training as males, including KKT, but with a lower standard of physical strength and endurance set. Female volunteers were trained separately from males.

Female Rannikkojääkärit volunteers in training - 1937

Divisional Structure

(See US Marine Corps Report and Assessment of the Finnish Marine Division dated 1935 in section below).

Development of Doctrine

The major influence on the Rannikkojääkärit was the US Marine Corps. As mentioned earlier, in late 1931, Marshal Mannerheim had arranged for a number of Officers to be attached to the Marine elements of a number of countries – generally half a dozen officers to each country’s forces. These included the British Royal Marines, the US Marine Corps, the French Troupes Coloniales, the Italian San Marco Battalion, the Royal Netherlands Marine Corps and the Spanish Infantería Marina (lest you doubt, this unit enjoyed success during the Third Rif War in its innovative Alhucemas amphibious assault in 1925, when it employed coordinated air and naval gunfire to support the assault – in 1931 it was officially determined to be a "colonial force" by the Republicans and was denounced as “an instrument of imperialism”. It was sentenced to extinction by the Spanish republican government in 1931 but was still in existence in 1932 when the Finnish Officers were attached to it briefly. From all these various units, the Finns absorbed a wide range of techniques, skills and doctrine.

While many countries were reducing or eliminating their Marine forces in the aftermath of WWI, the US Marine Corps had established their reputation of ferocity and toughness in the battles on the Western Front, including Belleau Wood. Between the World Wars, the Marine Corps was headed from 1920-29 by Commandant John A. Lejeune and under his leadership, the Corps presciently studied and developed amphibious techniques that would be of great use in World War II. At the period the Finnish Officers were attached, the Commandant was Major General Ben H Fuller (1930-33) who was a strong advocate of the Marine Fleet Force concept – essentially, combined arms operations for the Marines. Fuller went out of his way to facilitate the education of the Finnish Officers and initiated an exchange program in 1933 whereby Finnish Officers were attached to the US Marine Corps while US Marine Corps Officers and experienced NCO’s were attached to the Finnish Rannikkojääkärit. The largest group of US Marine Corps Officers and NCO’s served with the Rannikkojääkärit over 1934 and 1935, greatly facilitating the initial establishment of the Rannikkojääkärit, the development of training programs and both strategic and tactical doctrine suited to the Finnish strategic and tactical environment. These officers, together with a small team of US Marine Corp pilots and aircrew who assisted with the Helldiver training, were influential in the development of the combined arms combat techniques and doctrine which were used to great effect in the Winter War and during Finland’s involvement in the Second World War.

1935 Report on the Finnish Marine Jaeger Division prepared for the US Marine Corps (Authored by US Marine Corps Major (deleted), commander of the US Marines Training Detachment on attachment in Finland)

ORGANIZATION AND TRAINING OF FINNISH MARINES

________________________________________

Origin.

In 1934, the Finnish Navy established a Marine Division and requested assistance from the US Marine Corps in establishing structure and organisation, strategic and tactical doctrine and in the establishment of training programs. The Finnish Marine Division is loosely based on the US Marine Divisional organisation, but is strongly influenced by the Finnish Army’s “Combined Arms Regimental Battle Group” structure. The Division is heavily combat-oriented and is structured with far less “tail” than a US Marine Corps Division.

As with all Finnish military units, the Marine Division is largely a Reservist Unit, with the greater part of the personnel being Reservists who have completed their training during their period of Conscript Service. Reservists generally participate in a limited number of weekend training days throughout the year, as well as a one to two week Annual Exercise which is usually carried out at the Battalion level. As of the time of writing this report, 3 Trainee Intakes have completed training and the Division is at approximately half-strength. The Finnish Commanding Officer (Marine Division) estimates that by 1938, the Division will have trained sufficient Marines to be able to operate at full Divisional strength in the event of mobilization.

Selection of Personnel.

Selection of initial Officer and NCO Cadre was made from a combination of appointments by the Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces and volunteers from Army Cadre. All other personnel are volunteers doing their compulsory Conscript Service and these fill almost all positions within the Division. Finnish Marine policy is that all trainees must have completed their six month Army Basic Training successfully, and must be volunteers. The first Intake of trainees commenced in 1934, from Volunteers who had just completed their six months of Army Basic Training and consisted of 2,500 men and 350 women.

(Of Note is that the Finnish Marines accept women volunteers for service in non-Frontline positions – generally, women soldiers fill all rear-area service, clerical, support and quartermaster/stores positions. Women complete the same training as male Marines including all-arms combat training – albeit with lower physical fitness standards. Of particular note is that this releases large numbers of male Marines for combat unit roles, something the Finns emphasized was important given their limited manpower. Also of note is that ALL women Marines are always armed with personal weapons and are trained in their use).

Missions.

The primary mission of the Finnish Marines is to take the tactical offensive in counter-attacking any attempted enemy attacks along the Finnish coastline and archipelagoes or in winter, across the frozen sea-ice of the Gulf of Finland. Secondary roles are Raiding attacks on the enemy and the support of Army operations. The objectives of the Finnish Marines were stablished as being:

(1) To conduct counter attacks against enemy landings in the Finnish archipelago, an environment known for its many small islands and skerries,

(2) To carry out raiding attacks from the sea on enemy held positions and

(3) To carry out full-scale attacks from the sea in support of Army operations.

(4) Anticipating that the Gulf of Finland may become completely frozen over, allowing flanking attacks by the enemy across the Ice, to prepare for and be capable of fighting major defensive actions on the Ice while at the same time being capable of taking the tactical offensive against the enemy;

Organization.

The Marine Division functions under the Advisor for Combined Operations (A.C.O.). The A.C.O. acts in an advisory capacity to, and executes the orders of, the Commander-in-Chief of the Finnish Military (currently, Marshal Mannerheim). The staff of the A.C.O. consists of officers of the Maavoimat (Army), Merivoimat (Navy), Ilmavoimat (Air Force), and the Rannikkojääkärit (Marines). The Marine Division is commanded by a Major-General who has both an operational and an administrative staff. The Division, however, does not train, nor does it function normally as a Division, but as separate Regimental Battle Groups which are based in various parts of Finland. The Marine Division is entirely serviced by the Navy.

At this time, approximately 2,500 to 3,000 trainees undergo a six month training period, with two six-month Training Courses run in each year. At the end of the six month training period, Enlisted Marines have completed their compulsory period of military service and are released, at which time they move to “Reserve” status and are required to participate in a limited number of weekend training days together with a short Annual Camp. Current plans are to continue training at this level for the next two years, by which time the Division will have a sufficient number of trained Reservists to fully man the Division in the event of mobilization. At this stage, Marine Selection will become more stringent and selective, with the objective being to train replacement personnel on an ongoing basis.

There are no Direct Entry Officers in the Marines. Every Conscript enters as an Enlisted Man and completes six months of Army Basic Training. There are no exceptions to this requirement. Volunteers for the Marines then complete a two month Selection Course, during which potential Officers and NCO’s are marked by the Training Cadre. On successful completion of Selection, these Officer and NCO candidates are requested to volunteer for Officer and NCO Trainng, which requires 18 months of service overall rather than the 12 months completed by Enlisted Men. Men cannot apply for Officer and NCO Training – they must be selected by the Training Cadre based on their performance during Selection. Following completion of training, additional courses are available to Reservist Officers and NCO’s, who are all members of the Finnish Civil Guard, the Suojeluskuntas, which now has a “Marine” component to it.

The formal organisation of the Finnish Marine Division is as follows:

The Marine Division is made up of 3 Regimental Battle Groups with a Divisional HQ and a Training Wing attached to the Divisional HQ. Divisonal HQ is largely administrative and aside from logistical support and administration, is responsible for the Training of Marines, with approximately 2,500-3,000 volunteers in a Training Intake in any one six month period. Over 1934 and 1935, some 8,000 Marines have successfully completed training and are formed up into the 3 Regimental Battle Groups (currently these are all at approximately half strength. It is anticipated by the Divisional HQ that by year-end 1937, sufficient Marines will have been trained for all 3 Regimental Combat Groups to be up to strength on mobilization. In the event of mobilization, plans call for the current training Intake to be held back as “replacements” for casualties and for the next twelve months Intake Class to be called up and trained in one Intake, possibly to form a fourth Regimental Battle Group on completion of what would be “accelerated” training.

Regimental Battle Group

o Regimental HQ

- HQ

- Security Company

- Signals Company

- Recconaissance Company

- Pioneers Company (Engineers)

o Marine Strike Battalion I (Iskupataljoona – xxxx men)

o Marine Strike Battalion II (Iskupataljoona – xxxx men)

o Marine Strike Battalion II (Iskupataljoona – xxxx men)

o Heavy Weapons Battalion

- 2 x Field Artillery Battalions (12 Field Guns each, 24 in total)

- Anti-Aircraft Company (12 AA Guns)

- Mortar Company (12 x 81mm Mortars)

o Regimental Tail

- Supplies Company

- Ammunition Supply Company

- Transport Company

- Field Kitchen Company

- Field Hospital + Ambulance Platoon

- Vehicle Repair and Fuel Supply Unit

- Field Hospital for Horses

- Field Post Office

- Clothing Depot

Note that the Regimental Battle Group, as it is termed in Finnish military nomenclature, is a fully self-contained organisation with its own integral artillery battalions together with all necessary support, including logistics. Strategic assets are controlled at Corps or Military HQ level rather than subdivided down into Divisional assets.

Marine Strike Battalion (Iskupataljoona)

o Battalion HQ

- HQ

- Security Platoon

- Signals Platoon

- Recconaissance Platoon

o Strike Company I (Iskukomppania – 124 men)

o Strike Company II (Iskukomppania – 124 men)

o Strike Company III (Iskukomppania – 124 men)

o Support Company

- Mortar Platoon (4 x 81mm Mortars)

- Pioneer Platoon (Engineers)

- Anti-tank Platoon (4 x AT Guns)

- AA Gun Platoon (4 x AA Guns)

- Heavy Machinegun Platoon

o Logistics Company

- Transport Platoon

- Ammunition Supplies Platoon

- Supplies Platoon

- Boat Platoon

- Medical Platoon

- Battalion Admin Section

Marine boat transport varies as the Marine Division has no purpose-built boats (although planning has begun to acquire these, this is not expected to be completed in the short-term future). Marines are generallycarried to their destimation on Navy boats where these are available, otherwise civilian motor launches and fishing boats are used. Generally, each launch or boat is capable of transporting 1 to 2 sections of Marines and when I use, is fitted with a Maxim machinegun in the bow for fire support. The maximum speed of these boats is modest by military standards and the pace is usually set by the slowest boat of the group. Where motor boats are not available, rowing boats are used, and canoes are often used by the Reconnaissance Platoons.

While the TOE calls for large numbers of Mortars, Anti-tank Guns, AA Guns and Machineguns, these are generally not available. The Finnish Military have various acquisition programs underway and the apparent target is to have the TOE up to strength over as five year period. Much of the current strength in equipment is however only on paper.

Marine Strike Company ((Iskukomppania – 124 men)

o Company HQ (29 men)

- Company Commander

- Command Squad (6 man Sigs/Messenger Section, 4 man Sniper Section, 9 man AT Section)

- Supplies Section (1 Sgt, 7 men)

o Strike Platoon I (Iskukomppania – 32 men)

- Platoon Command Squad (1 Officer, 1 Sgt, 1 Sig, 2 Messengers, 1 Medic, 2 man Sniper Team)

- Rifle Squad I (Corporal, 2 man LMG Team, 2 SMG Men, 3 Riflemen)

- Rifle Squad II (8 men, as above)

- Rifle Squad III (8 men, as above)

o Strike Platoon II (Iskukomppania – 32 men)

o Strike Platoon III (Iskukomppania – 32 men)

Strike Companies are generally heavy on automatic firepower, with provision in the TOE for numerous light machineguns and submachineguns. The Marines also put a heavy emphasis on the use of Snipers (6 x 2 man Sniper Teams within the Company strength of 124 men). Provision is also made for 4 x 2 man Anti-Tank Rifle Teams under the control of the Company Command Squad, although at this time it should be noted that Anti-Tank Rifles are not available). The Marines also put a great deal of emphasis on Signals and communications. Plans are apparently underway for units down to the Platoon-level to be equipped with Radios at some stage (these are apparently under development in a secret project, details of which were not divulged – at present Field Telephones and Messengers are used). There is one Medic in each Platoon Command Squad and usually at least one man in each Section has also completed Medic Training. All Marines are expected to qualify as Expert Marksman, and Sniper Training is encouraged. Also noted was that the standard Section strength of 8 men is exactly suitable for embarking in the small Dory-type boats that the Marines use in training.

Weapons.

Although the establishment (Tables of Organization) provides a definite allowance and allocation of weapons, neither the numbers of weapons nor their distribution is rigidly adhered to. In every case the distribution of weapons is made according to the tactical requirements of the particular mission to be performed. Each Regimental Battle Group has a separate store of extra weapons and thus extreme flexibility in armament is assured. A typical store contains:

Maxim Machineguns; Suomi Submachineguns; 81mm mortars and a supply of both smoke and HE shell for each; defensive (fragmentation) hand grenades; smoke pots; Flare pistols; knuckle dusters; explosives for demolitions of all types.

Normally each Platoon is allocated one Maxim machinegun and one Suomi submachinegun per section. The allocation of the 81mm mortars is left entirely to the Commander who employs them according to the requirements of the situation. As indicated above, additional weapons are available in stores and may be assigned. The important point to note is the extreme flexibility in armament and the degree of initiative permitted Platoon and Company leaders in its distribution.

Clothing and Equipment.