The 1937 Procurement Program – continued….

Merivoimat Dive Bomber - Vought SB2U Vindicator – 20 ordered in late 1937

In their search for a Dive Bomber to equip a single Merivoimat Dive Bomber Squadron in 1937, the Procurement Team evaluated a number of different aircraft before making a decision. Among these were the American Vought SB2U Vindicator, Northrop BT, Curtiss SBC-3 Helldiver, Brewster SBA and Grumman SBF, the British Blackburn Skua and Hawker Henley, the French Loire-Nieuport LN 410, the German Ju87 and the Italian Breda BA-65 ground attack fighter. The overall evaluatuion and flight testing program was lengthy, with a decision not reached quickly and an order was placed only shortly before the end of the year. And eventually, as with other purchasing decisions made in 1937, the final and major influencing factor was the sizable US loan that had been made available in 1937.

Vought SB2U Vindicator

The Vought SB2U Vindicator was a carrier-based dive bomber developed for the United States Navy in the 1930s, the first monoplane in this role. In 1934, the United States Navy issued a requirement for a new Scout Bomber for carrier use, and received proposals from six manufacturers. The specification was issued in two parts, one for a monoplane, and one for a biplane. Vought submitted designs in both categories, which would become the XSB2U-1 and XSB3U-1 respectively. The biplane was considered alongside the monoplane design as a "hedge" against the U.S. Navy's reluctance to pursue the modern configuration.

The Vought SB3U-1 Corsair was a two seat, all metal biplane dive bomber built by Vought Aircraft Company of Dallas, Texas for the US Navy. The aircraft was equipped with a closed cockpit, had fixed landing gear, and was powered by a Pratt & Whitney R-1535 radial air-cooled engine. The SBU-1 completed flight tests in 1934 and went into production under a contract awarded in January 1935, with 125 being built. The Corsair was the first aircraft of its type, a scout bomber, to fly faster than 200 mph. Maximum speed was 205mph, range was 548 miles and armament consisted of 1x Fixed forward firing .30 in (7.62 mm) Browning machine gun and 1x machine gun flexibly mounted .30 in machine gun in rear cockpit and 1 x 500lb bomb. This aircraft was not evaluated by the Ilmavoimat – introduced into service in 1935, by 1937 it was already outdated.

The Vought SB3U-1 Corsair was a two seat, all metal biplane dive bomber built by Vought Aircraft Company of Dallas, Texas for the US Navy. The aircraft was equipped with a closed cockpit, had fixed landing gear, and was powered by a Pratt & Whitney R-1535 radial air-cooled engine. The SBU-1 completed flight tests in 1934 and went into production under a contract awarded in January 1935, with 125 being built. The Corsair was the first aircraft of its type, a scout bomber, to fly faster than 200 mph. Maximum speed was 205mph, range was 548 miles and armament consisted of 1x Fixed forward firing .30 in (7.62 mm) Browning machine gun and 1x machine gun flexibly mounted .30 in machine gun in rear cockpit and 1 x 500lb bomb. This aircraft was not evaluated by the Ilmavoimat – introduced into service in 1935, by 1937 it was already outdated.

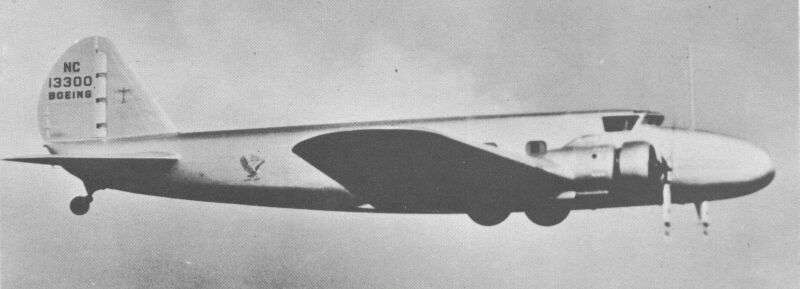

By way of contrast, the Vought XSB2U-1 was a conventional low-wing monoplane configuration, with a retractable tailwheel undercarriage and the pilot and tail gunner seated in tandem under a long greenhouse-style canopy. The fuselage was of steel tube construction, covered with aluminum panels from the nose to the rear cockpit, and with a fabric covered rear fuselage, while the folding cantilever wing was almost completely fabric except for a metal leading edge. A 700hp Pratt & Whitney R-1535 Twin-Wasp Junior radial engine drove a two-blade constant-speed propeller, which was intended to act as a dive-brake during a dive bombing attack. A single 1,000 lb (450 kg) bomb could be carried on a swinging trapeze to allow it to clear the propeller in a steep dive, while further bombs could be carried under the wings to give a maximum bombload of 1,500 lb (680 kg).

Designated XSB2U-1, one prototype was ordered by the US Navy on 15 October 1934 and was delivered on 15 April 1936. Accepted for operational evaluation on 2 July 1936, the prototype XSB2U-1, BuNo 9725, crashed on 20 August 1936. During the Navy tests a number of problems were uncovered. It had been intended to equip the aircraft with a reversible propeller to act as a dive brake; however, this proved to be difficult to use and became technically unsatisfactory. As a replacement, Vought constructed a dive flap that consisted of a number of finger-like spars mounted near the wing leading edge that, during normal flight, were flush with the wing surface but during a dive could be extended at right angles to the wing surface to slow the aircraft. These flaps failed to work satisfactorily because they caused so much drag that full engine power was needed to maintain control. Additionally, the flaps caused severe aileron buffeting, and weighed some 140 pounds. As a result, the Navy decided to adopt a shallower dive angle and to extend the landing gear to act as a form of dive brake. The prototype was also modified to include additional bracing on the pilots and observers canopies. The successful completion of trials led to an initial order for 54 aircraft from the US Navy in October 1936.

The Ilmavoimat evaluated the Vindicator early in 1937. While they rated the aircraft highly, the Procurement Team went on to evaluate a number of other Dive Bombers before reaching a final decision to purchase the Vindicator in late 1937. An order was placed for 20 of the aircraft. Delivery took place in June 1938 and the Vindicators entered service shortly thereafter.

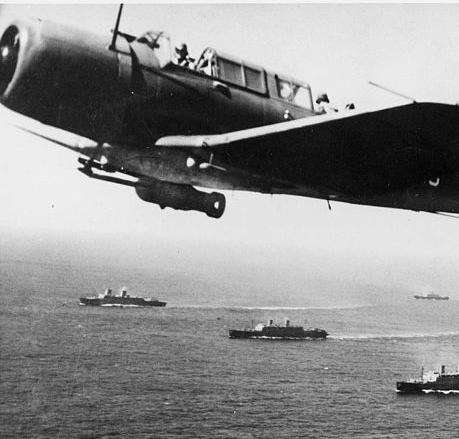

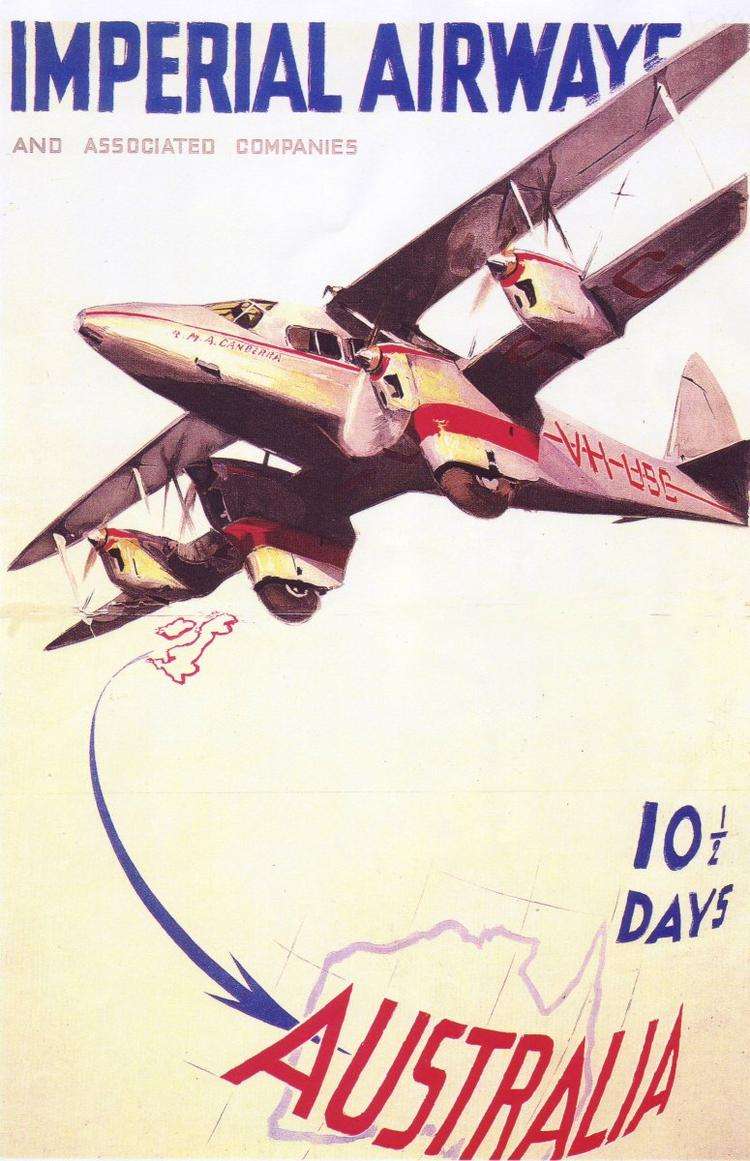

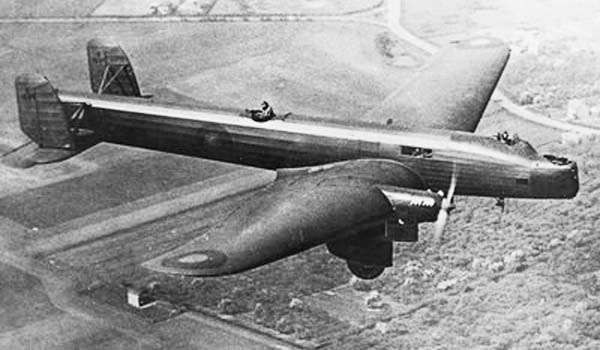

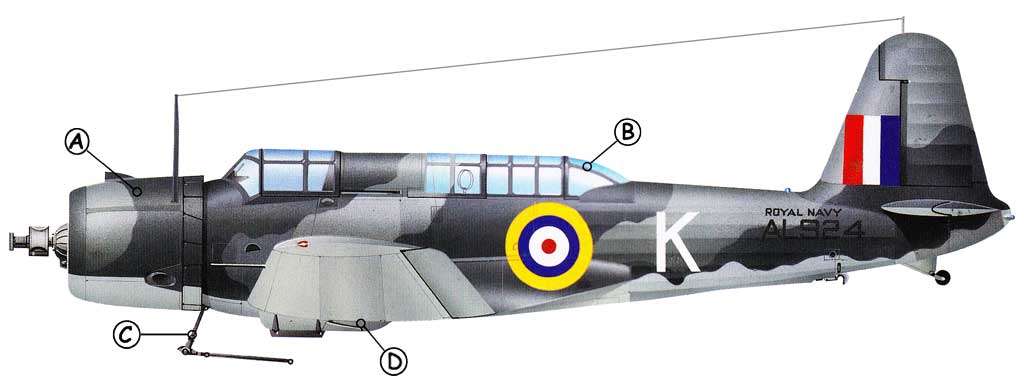

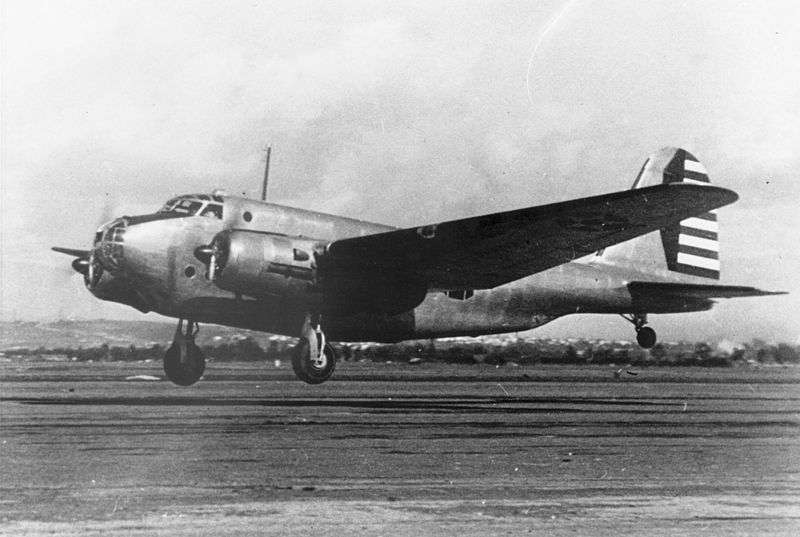

Merivoimat Vought Vindicator escorting ships of the Helsinki Convoy through the Baltic north of Gotland, Spring 1940. With a crew of 2 (Pilot and Gunner) and powered by a single Pratt & Whitney R-1535-96 Twin Wasp Jr radial engine of 825 hp (616 kW), the Merivoimat Vindicators had a maxiumum speed of 251mph. Additional fuel tanks were added after delivery, increasing the range from 630 miles to some 800 miles and a service ceiling of 27,500 feet. The Merivoimat version was armed with four forward firing machineguns in the wings and one machinegun in a flexible mount for the rear-facing gunner. Bombload consisted of one 1,000lb or one 500lb bomb.

Merivoimat Vought Vindicator escorting ships of the Helsinki Convoy through the Baltic north of Gotland, Spring 1940. With a crew of 2 (Pilot and Gunner) and powered by a single Pratt & Whitney R-1535-96 Twin Wasp Jr radial engine of 825 hp (616 kW), the Merivoimat Vindicators had a maxiumum speed of 251mph. Additional fuel tanks were added after delivery, increasing the range from 630 miles to some 800 miles and a service ceiling of 27,500 feet. The Merivoimat version was armed with four forward firing machineguns in the wings and one machinegun in a flexible mount for the rear-facing gunner. Bombload consisted of one 1,000lb or one 500lb bomb.

Within the US Navy, the Vindicator was by now well-tried and popular. However, by late 1938 it was beginning to be phased out as the new Douglas SBD Dauntless aircraft began to be delivered. Both the US Navy and Vought were wondering what to do with the surplus Vindicators. This was opportune for Finland. Early in 1939, with the threat of war with the USSR increasingly a risk and the deteriorating European situation, the Finnish Finance Minister, Risto Ryto, had negotiated a further loan from the USA (although not in the same ballpark as the 1937 $30 million amount) and additional war supplies were being purchased whereever they were available. Among these purchases were a further 20 US Navy surplus Vindicators. These were well-used, but as second hand aircraft the cost was significantly reduced and they were shipped to Finland in summer 1939, along with a number of other second hand aircraft that had been purchased (these will be covered when we get to cover 1939 and the Emergency Procurement Program of that year, which was allocated some 45% of all Finnish State spending, significantly reducing funding for every other government program, albiet with some major but as it proved, short-lived, political fallout).

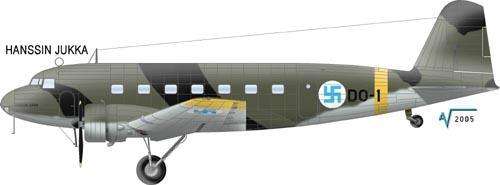

In the event, the ex-US Navy Vindicators arrived in August 1939 and had not yet even been repainted as the Winter War broke out. Still with their US markings in many cases, they were pressed into service immediately – such was the tempo of operations that some of these aircraft were not reflagged until March 1940 – something which led to accusations from the USSR that US forces were assisting Finland.

In the event, the ex-US Navy Vindicators arrived in August 1939 and had not yet even been repainted as the Winter War broke out. Still with their US markings in many cases, they were pressed into service immediately – such was the tempo of operations that some of these aircraft were not reflagged until March 1940 – something which led to accusations from the USSR that US forces were assisting Finland.

Another and later source of supply were Vindicators that had been ordered for the French Air Force. The V156 (the export version of the Vindicator) was shown at the Paris Air Show in November 1938 and French interest had been aroused. The French Government decided in May 1938 to order ninety Vindicators as their own dive bomber program was falling apart. The first five were delivered to Orly in July 1939 and more were on the way as WW2 broke out. Some forty in all were delivered before Franch fell to the German onslaught. Circumventing the US Neutrality legislation, a further thirty Vindicators from the remaining French order, which had been already been repainted for sale to the UK, were reallocated to Finland and shipped to Petsamo in June 1940, entering service only in the final month of the Winter War where they saw little action.

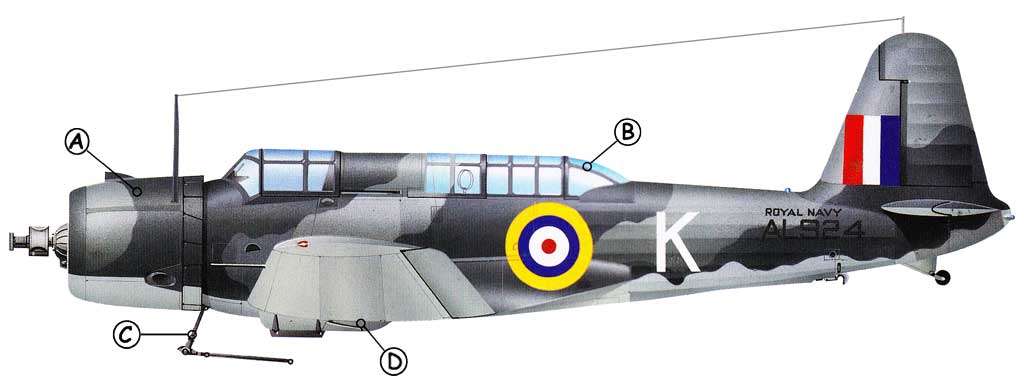

Vought Vindicators ordered for France, resold to the British and then side-tracked for urgent delivery to Finland in June 1940…..they entered service with the Merivoimat Air Arm in September 1940 and saw little or no action.

Northrop BT

Vought Vindicators ordered for France, resold to the British and then side-tracked for urgent delivery to Finland in June 1940…..they entered service with the Merivoimat Air Arm in September 1940 and saw little or no action.

Northrop BT

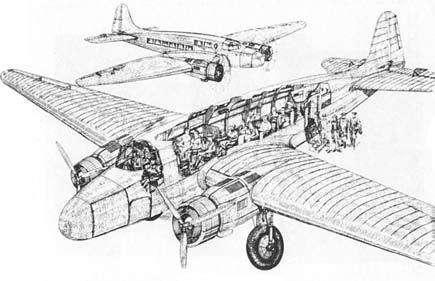

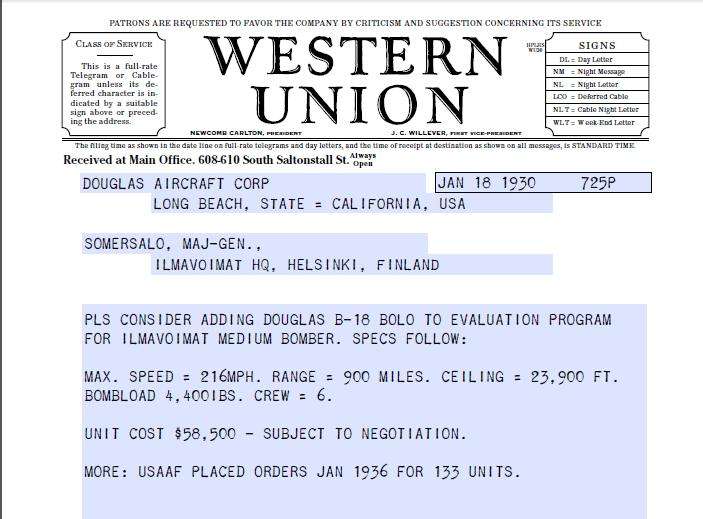

The Northrop BT was a two seat, single engine, monoplane, dive bomber built by the Northrop Corporation for the United States Navy at a time when Northrop was a subsidiary of the Douglas Aircraft Company. The design of the initial version began in 1935. The Northrop XBT-1 had been entered in the competition as a combination dive bomber/scout aircraft and the Navy decided to develop the design as a dive bomber. The first prototype was powered by a 700 hp (522 kW) Pratt and Whitney XR-1535-66 Twin Wasp Jr. double row, radial air-cooled engine. The aircraft had slotted flaps and a landing gear that partially retracted. The next iteration of the BT, designated the XBT-1 was equipped with a 750 hp (559 kW) R-1535 engine. This aircraft was followed in 1936 by the BT-1 that was powered by an 825 hp Pratt and Whitney R-1535-94 engine. One of the BT-1 aircraft was modified with a fixed tricycle landing gear and was the first such aircraft to land on an aircraft carrier.

The Ilmavoimat/Merivoimat team evaluated the BT-1 in early 1937, but at this stage the prototype was undergoing a redesign to address issues indentified in testing.The aircraft was eliminated from consideration at this point, although it was agreed that it would be reevaluated following completion of the next version prototype. The final variant, the XBT-2, was a BT-1 aircraft modified to incorporate a fully retracting landing gear, wing slots, a redesigned canopy, and was powered by an 800 hp (597 kW) Wright XR-1820-32 radial air-cooled engine. The XBT-2 first flew on 25 April 1938 and after testing the US Navy placed an order for 144 aircraft. In 1939 the aircraft designation was changed to the Douglas SBD-1 with the last 87 on order completed as SBD-2s. The Northrop Corporation had become the El Segundo division of Douglas aircraft hence the change to Douglas. The U.S. Navy placed an order for 54 BT-1s in 1936 with the aircraft entering service during 1938. The BT-1s served on the USS Yorktown and Enterprise. The type was not a success in service due to poor handling characteristics, especially at low speeds, "a fatal flaw in a carrier based aircraft." It was also prone to unexpected rolls and a number of aircraft were lost in crashes.

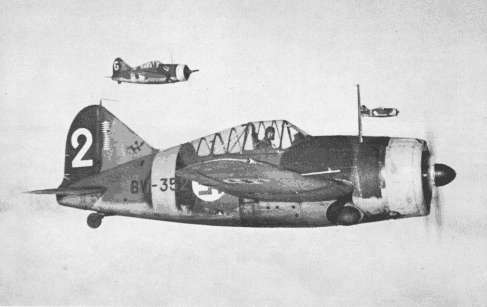

Northrop BT-1s over Miami in October 1939. With a crew of 2 (Pilot and Gunner), the BT-1 was powered by a single Pratt & Whitney R-1535-94 Twin Wasp Jr. double row radial air-cooled engine of 825 hp (615 kW), giving a maximum speed of 222mph with a range of 1,150 miles and a service ceiling of 25,300 feet. Armament consisted of one forward and one rear-facing machinegun and a 1,000lb bomb carried under the fuselage.

Curtiss SBC-3 Helldiver

Northrop BT-1s over Miami in October 1939. With a crew of 2 (Pilot and Gunner), the BT-1 was powered by a single Pratt & Whitney R-1535-94 Twin Wasp Jr. double row radial air-cooled engine of 825 hp (615 kW), giving a maximum speed of 222mph with a range of 1,150 miles and a service ceiling of 25,300 feet. Armament consisted of one forward and one rear-facing machinegun and a 1,000lb bomb carried under the fuselage.

Curtiss SBC-3 Helldiver

The Curtiss SBC Helldiver was a two-place scout bomber built by the Curtiss-Wright Corporation. It was the last military biplane procured by the United States Navy. In 1932, the U.S. Navy gave Curtiss a contract to design a parasol two-seat monoplane with retractable undercarriage and powered by a Wright R-1510 Whirlwind, intended to be used as a carrier-based fighter. The resulting aircraft, designated the XF12C-1, flew in 1933. Its chosen role was changed first to a scout, and then to a scout-bomber (being redesignated XS4C-1 and XSBC-1 respectively), but the XSBC-1's parasol wing was unsuitable for dive bombing. A revised design was produced for a biplane, with the prototype, designated the XSBC-2, first flying on 9 December 1935.

The SBC-3 was the initial production model and was powered by a Pratt & Whitney R-1535 Twin Wasp Junior. The SBC-3 began operational service in 1938. A total of 83 SBC-3s were built. The SBC-4 was powered by a Wright R-1820 Cyclone. The SBC-4 entered service in 1939 with 174 SBC-4s in all being built. The US Navy took deliveries of the new aircraft in mid-1937 with the first batch of carrier-based aircraft going to the Yorktown, but time and technology caught up to the advanced biplane. The Finnish procurement team evaluated and tested a prototype aircraft in early 1937 but even at that stage, before it had enetered service, considered it an outdated design with inadequate performance. It was crossed off the list.

In US service, the SBC-4 was soon relegated to hack duties and service as an advanced trainer for training units in Florida. Within the US Navy, the SBC Helldiver was not destined to have a long U.S. service life, but its impact was felt as the type made a lasting contribution by serving as the key platform in developing dive bombing tactics and honing aircrew skills crucial to winning the war in the Pacific.The last aircraft was stricken from the Navy roster in October 1944. Aware of the use being made of the SBC-4 Helldivers in early 1939 on hack duties and service as an advanced trainer, the Finnish Procurement Team in Washington DC pressed the US to sell these to Finland as a matter of urgency, even going so far as to have the Finnish Ambassador in the US directly raise the matter with President Roosevelt. However, in this instance nothing successful was achieved and in the end some 50 SBC-4s were delivered to the French Navy. The 50 SBC-4s delivered to France were actually aircraft already in service with the United States Navy.

The Curtiss SBC Helldiver Biplabe had a crew of 2 (Pilot and Gunner), was powered by a single Wright R-1820-34 radial engine of 850 hp (634 kW) with a maximum speed of 234mph, a range of 405 miles and a service ceiling of 24,000 feet. Armament consisted of two machineguns (one forward facing, one rear) and one 1,000lb bomb.

The Curtiss SBC Helldiver Biplabe had a crew of 2 (Pilot and Gunner), was powered by a single Wright R-1820-34 radial engine of 850 hp (634 kW) with a maximum speed of 234mph, a range of 405 miles and a service ceiling of 24,000 feet. Armament consisted of two machineguns (one forward facing, one rear) and one 1,000lb bomb.

On 6 June 1940, Naval reservists received orders to immediately fly 50 SBC-4s to the Curtiss factory at Buffalo, New York. At Buffalo, a Bureau of Aeronautics inspector informed the pilots their aircraft were to be flown to Halifax, Nova Scotia to be loaded aboard the French aircraft carrier Béarn. From Buffalo to Halifax, the reserve pilots were officially employees of Curtiss. Curtiss paid each pilot $250 plus return rail fare from Halifax to Buffalo. All navy insignia were removed from their uniforms or taped over. Upon return to Buffalo, the pilots went back on Navy orders for return to their home bases. Curtiss employees worked overtime to remove and replace all gear and instruments marked BUAERO, BUSHIPS or BUORD. The Navy .30 in (7.62 mm) machine guns were replaced by .50 in (12.7 mm) guns and the aircraft were repainted in camouflage colors with the French tricolor on the rudders. The hasty conversion did not allow time for adequate checkout of replacement instruments. Weather deteriorated with rain and fog over most of the route from Buffalo to Halifax. The Bureau of Aeronautics inspector temporarily halted flights after one of the first pilots was killed in a crash between Buffalo and Albany.

When the weather improved, sections of three aircraft were dispatched from Buffalo Houlton, Maine. After landing at Houlton, the aircraft were towed down a road across the Canadian border for takeoff from a New Brunswick farm pasture to avoid legal implications of flying over the border. The surviving 49 aircraft flew over the Bay of Fundy and 44 of them were loaded aboard Béarn at Dartmouth, Nova Scotia together with 21 P-36 Hawk fighters and 25 Stinson 105s for the French Armée de l'Air and five Brewster Buffalos for Belgium. France surrendered while Béarn was crossing the Atlantic; she turned south to Martinique, where the SBC-4s corroded in the humid Caribbean climate while waiting on a hillside near Fort-de-France. The five SBC-4s remaining in Canada when France surrendered were taken over by the United Kingdom and were used as ground-instructional airframes. Nothing practical was gained, and Finland missed out on what could have been a reasonably adequate ground attack aircraft. Fortunately, other aircraft were available and it was not a critical loss.

Brewster SBA

The SBN was a United States three-place mid-wing monoplane scout bomber/torpedo aircraft designed by the Brewster Aeronautical Corporation and built under license by the Naval Aircraft Factory in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The United States Navy issued a specification for a scout-bomber in 1934 and the competition was won by Brewster. One prototype designated the XSBA-1 was ordered on October 15, 1934. The prototype first flew on April 15, 1936, and was delivered to the Navy for testing. Some minor problems were found during testing and the aircraft was given a more powerful engine.

The Ilmavoimat evaluation identified the production bottleneck issues with this aircraft and despite the promising performance of the prototype, it was eliminated from the shortlist as a result. Events proved this to be a correct decision.

With a Crew of 3 (Pilot, Navigator, Gunner), a single Wright XR-1820-22 Cyclone radial engine of 950 hp (709 kW) giving a maximum speed of 254 mph, a range of 1015 miles, a service ceiling of 28,300 feet and armed with one rearward firing machinegun, the SBN carried up to 500lb of bombs.

With a Crew of 3 (Pilot, Navigator, Gunner), a single Wright XR-1820-22 Cyclone radial engine of 950 hp (709 kW) giving a maximum speed of 254 mph, a range of 1015 miles, a service ceiling of 28,300 feet and armed with one rearward firing machinegun, the SBN carried up to 500lb of bombs.

Because of the pressures of producing and developing the Brewster F2A the company was unable to produce the aircraft and the Navy acquired a license to produce the aircraft itself at the Naval Aircraft Factory. In September 1938 the Navy placed an order for 30 production aircraft. Due to pressures of work at the NAF it did not deliver the first aircraft, now designated the SBN, until 1941 and the remaining aircraft were delivered between June 1941 and March 1942.

Grumman SBF

In late 1934, the U.S. Navy's Bureau of Aeronautics (BuAer) issued a specification for new scout and torpedo bomber designs. Eight companies submitted 10 designs in response, evenly split between monoplanes and biplanes. Grumman, having successfully provided the FF and F2F fighters to the Navy, along with the SF scout, submitted an advanced development of the SF-2 in response to the specification's request for a 5,000 lb (2,300 kg) aircraft capable of carrying a 500 lb (230 kg) bomb. Given the model number G-14 by Grumman, the aircraft received the official designation XSBF-1 by the Navy, and a contract for a single prototype was issued in March 1935.

The XSBF-1 was a two-seat biplane, featuring an enclosed cockpit, a fuselage of all-metal construction, and wings covered largely with fabric. Power was provided by a 650 hp (480 kW) Pratt & Whitney R-1535 Twin Wasp Junior air-cooled radial engine driving with a variable-pitch propeller. Armament was planned to be two .30 in (7.62 mm) forward-firing M1919 Browning machine guns, one of which could be replaced by a .50 in (12.7 mm) M2 Browning; the prototype carried only a single gun. A single .30 in weapon was fitted in the rear cockpit for defense, and one 500 lb (230 kg) bomb was to be carried in a launching cradle under the fuselage. The arrestor hook was carried in a fully enclosed position, while flotation bags were fitted in the wings in case the aircraft was forced to ditch. The landing gear of the XSBF-1 was similar to that of the F3F fighter.

The XSBF-1—piloted by test pilot Bud Gillies—flew for the first time on December 24, 1935. Following initial testing, which found the aircraft to be reasonably faultless, the XSBF-1 was delivered to the U.S. Navy for evaluation in competition with two other biplanes submitted to the 1934 specification, the Great Lakes XB2G and the Curtiss XSBC-3. Unusually for biplanes, all three types possessed retractable landing gear. The evaluation showed that the design from Curtiss was superior to the Grumman and Great Lakes designs, and an order was placed for the Curtiss type, designated SBC-3 Helldiver in service, in August 1936.

Given the US rejection of the aircraft, the Ilmavoimats evaluation of the prototype was cursory at best – it had been assigned to the Naval Air Station at Anacostia where it was being used for continued testing and as a hack aircraft.

With a Crew of 2, the Grumman SBF had a maximum speed of 215mph, a range of 525 miles and a service ceiling of 26,000 feet. Amed with two machineguns (one forward-firing, one rear-facing, it could carry up to a 500lb bombload.

Blackburn Skua – evaluated 1937

With a Crew of 2, the Grumman SBF had a maximum speed of 215mph, a range of 525 miles and a service ceiling of 26,000 feet. Amed with two machineguns (one forward-firing, one rear-facing, it could carry up to a 500lb bombload.

Blackburn Skua – evaluated 1937

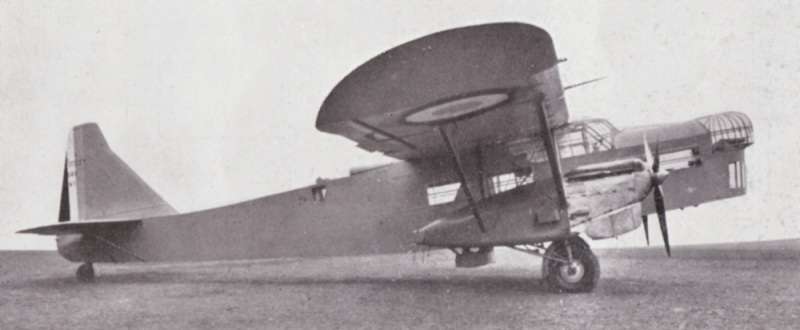

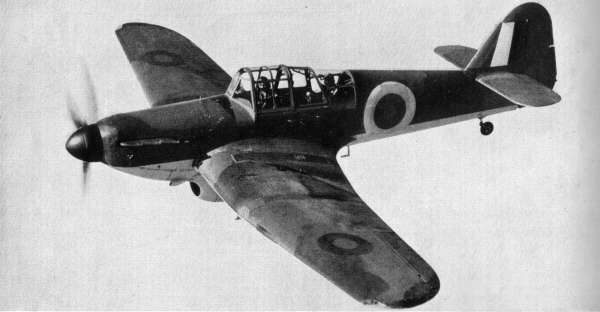

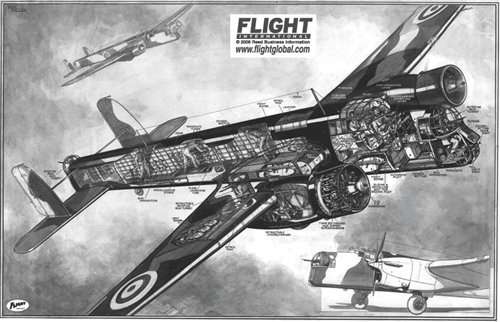

The Blackburn B-24 Skua was a carrier-based low-wing, two-seater, single-radial engine aircraft operated by the British Fleet Air Arm which combined the functions of a dive bomber and fighter. Built to Air Ministry specification O.27/34, it was a low-wing monoplane of all-metal (duralumin) construction with a retractable undercarriage and enclosed cockpit. It was the Fleet Air Arm's first service monoplane, and was a radical departure for a service that was primarily equipped with open-cockpit biplanes such as the Fairey Swordfish. Performance for the fighter role was compromised by the aircraft's bulk and lack of power, resulting in a relatively low speed; the contemporary marks of Messerschmitt Bf 109 made 290 mph (467 km/h) at sea level over the Skua's 225 mph (362 km/h). However, the aircraft's armament of four fixed, forward-firing 0.303 in (7.7 mm) Browning machine guns in the wings and a single flexible, rearward-firing Lewis .303 in (7.7 mm) machine gun was effective for the time (although whenever possible the gunner would try to replace this with a Vickers "K" gun which was more reliable and had a higher rate of fire).

For the dive-bombing role, a single 250 lb (110 kg) or 500 lb (230 kg) bomb was carried on a special swinging crutch under the fuselage, which enabled the bomb to clear the propeller arc on release. Four 40 lb (20 kg) bombs or eight 20 lb (9 kg) Cooper bombs could also be carried in racks under each wing. The 500lb AP and SAP bomb was only used against armoured warships, for attacks on merchant ships and ground targets the normal bombload was a 250 lb bomb in the fuselage recess and either 20lb or 40lb bombs on the light series carriers. The 250 lb bomb had only a little less explosive content than the 500lb SAP and AP bombs (the extra weight of the latter was down to the casing, needed to punch through armour). If used against ground targets the SAP and AP bombs would often bury themselves deep before exploding, reducing the blast effect. The small and largely ineffective 100 lb anti-submarine (AS) bomb could also be carried in the fuselage recess.

Powered by a Bristol Perseus XII nine cylinder, sleeve valve, air cooled radial engine rated at 815 hp, the Skua had a maximum speed of 225mph, a service ceiling of 20,500 ft (reached in 43 mins - the Skua had a very poor rate of climb) and maximum range of some 760 miles (an endurance of over 4 hours). It had large Zap-type air brakes/flaps which helped both in dive bombing and landing on aircraft carriers at sea.

Powered by a Bristol Perseus XII nine cylinder, sleeve valve, air cooled radial engine rated at 815 hp, the Skua had a maximum speed of 225mph, a service ceiling of 20,500 ft (reached in 43 mins - the Skua had a very poor rate of climb) and maximum range of some 760 miles (an endurance of over 4 hours). It had large Zap-type air brakes/flaps which helped both in dive bombing and landing on aircraft carriers at sea.

The first prototype Skua had problems with stability and it and the second prototype (both known as Skua MK Is) had to be modified with a longer nose and upturned wingtips, features carried over to the production aircraft (known as Skua Mk IIs). The spin characteristics of the Skua were bad enough to prompt the fitting of an anti-spin parachute in the tail to aid recovery. Interestingly, the Skua was designed with a very specific task in mind, the sinking of enemy aircraft carriers, for which its single 500 lb bomb would have been more than adequate (only Britain developed and deployed aircraft carriers with armoured decks during World War II). The role of fighter was intended as secondary. In combat however the Skua was forced to be used as a fighter much more often than as a dive bomber. Its performance as a fighter was often better than might be imagined just by looking at its modest speed in level flight. Its long endurance also meant it could loiter at altitude (once it got there, it had a very poor rate of climb) and dive onto its victims. Where the Skua had the potential to be badly misused was in attacks against heavily armoured warships, where its 500 lb bomb would cause little damage.

Two prototypes were ordered in 1935 with the first prototype (K5178) flying nearly two years later on 9th Feb 1937. It was this first prototype that the Ilmavoimat evaluated in mid-1937. While the test pilots liked the Skua’s handling, the aircraft could only carry half the bombload of the Vindicator (which was the leading choice at this stage), was slower and had less range. The Ilmavoimat decided at this stage to eliminate the Skua from consideration but to revisit the aircraft after it entered production.

In the UK, in October of 1937 the first prototype went on to handling trials at A.&A.E.E. Martlesham. The second prototype (K5179) did not fly until 4th May 1938, and the first production Skua (L2867) flew on 28th August 1938. A total of 190 Skuas had been ordered as far back as July 1936, even before the first prototype had flown. Thus production was started a full two years after the order. However deliveries were prompt after that and over 150 had been delivered by the time WW2 started, with all but one being delivered by the end of 1939. This meant that the Skua was very much a "new" aircraft when it first went to war and its pilots were still finding their way in this big metal monoplane aircraft with its retractable undercarriage and enclosed cockpits, all a novelty to British carrier pilots of the time. It is interesting to speculate what might have happened if the original expected "in-service" date of 1937 had been kept to. Then the crews would have had two years to get to know their aircraft and the Navy would probably have had 4 or 5 fully equipped and trained Skua Squadrons "ready to go" at the outbreak of war.

One further weakness of the Skua was that, as delivered to the British Fleet Air Arm, the Skua’s only means of radio communication was by Morse code back to the carrier. There was no speach-based radio communication with the carrier and not even Morse code communication with other Skuas. This meant communication between aircraft was limited to hand-signals or Aldis-lamp. This must have severely limited the ability of the Skua crews to co-operate, particularly in the fighter role - No "Tally Ho Red Leader, bandits 9 o'clock low" for the poor Skua pilots!

Hawker Henley

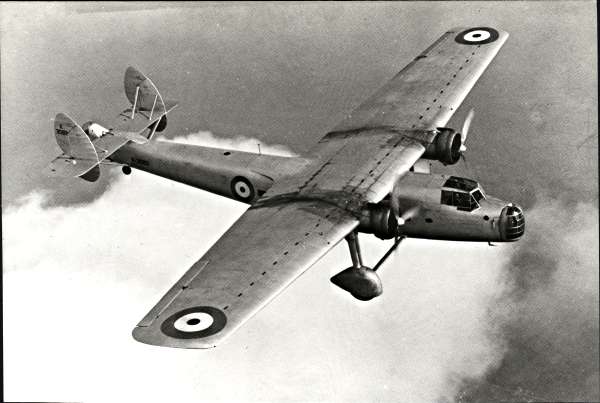

The Hawker Henley was designed as a light bomber in response to British Air Ministry Specification P.4/34 of February 1934 for a light bomber and close support aircraft, with high performance and a low bomb load. It was however to be fully stressed for dive bombing and a speed of 300mph was mentioned. The resulting aircraft was very similar in appearance to the Hurricane, sharing most of the wing and the tail plane with that aircraft as well as many of the assembly jigs. The main difference between the two types was the cockpit, with the Henley designed to carry a two man crew – pilot and observer/ air gunner. Work on the Henley progressed slowly. The prototype took two years to complete, finally taking to the air on 10 March 1937. It could carry 4 x 500lb bombs on underwing racks. The Henley performed well in tests, but three years after issuing the initial specification the Air Ministry decided it no longer needed a new light bomber. However, rather than cancel the Henley, the Air Ministry decided to use the aircraft as a target tug. Somewhat ironically the Hawker Hurricane would later go on to perform a role very similar to that originally intended for the Henley, acting as a ground attack aircraft.

The Ilmavoimat/Meroivoimat Procurement Team evaluated and test flew the aircraft and considered it outstanding, placing it first in the overall rankings of the aircraft they evaluated. For financial reasons, the Vindicator was selected over the Henley for the Merivoimat’s first Dive Bomber Squadron. However, the Ilmavoimat would revisit the question of purchasing the Hawker Henley some two months later, in January 1938.

In RAF service, the Henley was not a great success as a target tug. The first modified Henley TT.III flew on 26 May 1938, and an order was placed for 200. In service it was discovered that the Merlin engine could not cope with high speed target towing. After a brief period towing large drogue targets, the Henley was retired in May 1942, in favour of the Boulton Paul Defiant, which was itself obsolescent as a front line aircraft. As a Target Tug, the Henley was powered by a 1,030hp Rolls Royce Merlin II or III with a maximum speed of 272 mph with an air-to-air target or 200mph with an air-to-ground target. It had a ceiling of 27,000 feet, a range of 950 miles and was unarmed.

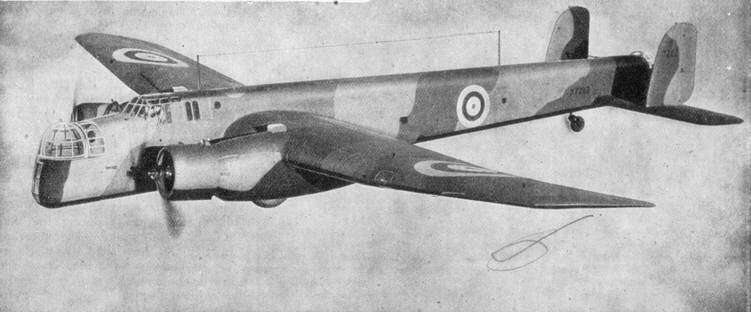

RAF Hawker Henley Target Tug

Loire-Nieuport LN 410

RAF Hawker Henley Target Tug

Loire-Nieuport LN 410

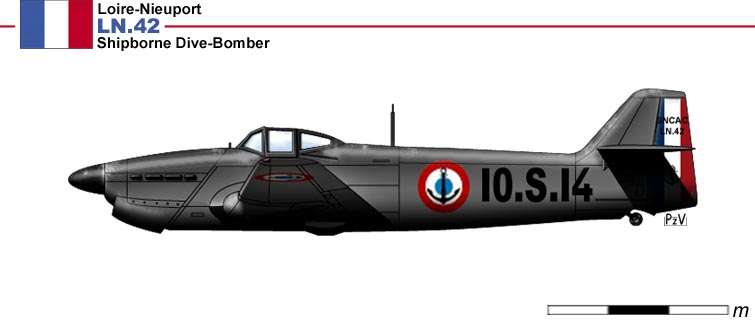

In late 1937, as has been mentioned in passing, the Finnish Government (Minister of Finance Risto Ryti) negotiated a loan with the French Government for some USD-equivalent-$8 million for the purchase of military equipment. As always, the bulk of the money went for equipment for the Maavoimat, but the Merivoimat were allocated enough of the loan to buy the old Russian naval guns in storage at Bizerte which were used to strengthen Finland’s coastal defences. And the Ilmavoimat were allocatred funds sufficient to buy a number of French aircraft. What the Ilmavoimat wanted was the Morane-Saulnier MS.406 – then perhaps the best of the French Fighters that were coming into service. With their rearmament program for the Armée de l'Air falling behind, the French declined to sell these but did offer to sell Finland the Arsenal VG-30, a cheap and lightweight fighter of wooden construction capable of being built quickly. The Finnish procurement team in France declined this offer, but became aware later in 1938 of the dive-bomber development program underway at the French company of Loire-Nieuport.

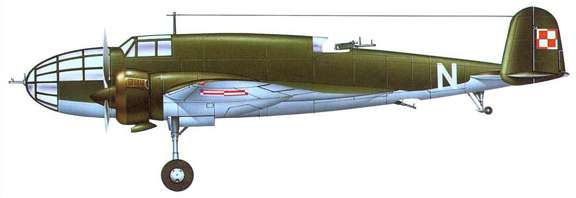

Between 1932 and 1936, Loire-Nieuport had been developing a two-seat dive bomber, the Nieuport 140, for the Aéronautique Navale, the aviation arm of the French Navy. It was renamed Loire-Nieuport LN.140 after the Nieuport company was absorbed into Loire-Nieuport in 1933. In 1936, the development of the LN.140 was abandoned after two fatal accidents. Development efforts were then concentrated on the LN.40 project which benefited from experience acquired with the LN.140, but was a new, and aerodynamically much more refined, design. In the second half of 1937 the LN.40 received government backing in the form of an order for a prototype, followed by orders for seven production aircraft destined for the aircraft carrier Béarn and three more for operational evaluation by the air force. The French Air Force also expressed interest in a land-based derivative of the LN.40, called LN.41. Initially it wanted to acquire 184 of these, enough to equip six dive bomber squadrons of 18 aircraft each, plus a reserve.

The prototype made its first flight on 6 July 1938, flown by Pierre Nadot and this was evaluated by an Ilmavoimat Test Team. The flight tests were not entirely successful. The original dive brake was found ineffective and during the Ilmavoimat tests was removed in favour of extending the landing gear to act as an aerodynamic brake. It was also found that the LN.40 could not fly dive bombing missions with full fuel tanks and the test team decided the aircraft was too slow, with a maximum speed of only 236mph.

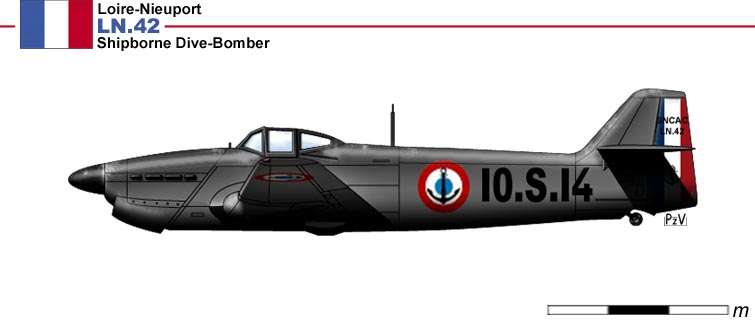

The LN.411 had a maximum speed of 236mph, a range of 745 miles and could carry a 500lb bomb. The Ilmavoimat at this stage declined to pursue the aircraft further but the Merivoimat remained interested and in August 1938 Loire-Nieuport agreed to work with the Merivoimat team on design improvements.A Hispano-Suiza 12Y engine was substituted for the LN.40’s older 690 hp Hispano-Suiza 12Xcrs engine, the tail surfaces wer eenlarged and the wing was extensively redesigned. A prototype for what was designated the LN.42 flew on 18 November 1938. Performance improvements however were disappointing and it was decided not to pursue the LN.42 further.

The LN.411 had a maximum speed of 236mph, a range of 745 miles and could carry a 500lb bomb. The Ilmavoimat at this stage declined to pursue the aircraft further but the Merivoimat remained interested and in August 1938 Loire-Nieuport agreed to work with the Merivoimat team on design improvements.A Hispano-Suiza 12Y engine was substituted for the LN.40’s older 690 hp Hispano-Suiza 12Xcrs engine, the tail surfaces wer eenlarged and the wing was extensively redesigned. A prototype for what was designated the LN.42 flew on 18 November 1938. Performance improvements however were disappointing and it was decided not to pursue the LN.42 further.

The Loire-Nieuport LN42 had a maximum speed of 267mph, a service ceiling of 9800m and a range of 857 miles. Armament consisted of 500kg of bombs, 1x20mm HS Cannon and 2 machineguns.

The Loire-Nieuport LN42 had a maximum speed of 267mph, a service ceiling of 9800m and a range of 857 miles. Armament consisted of 500kg of bombs, 1x20mm HS Cannon and 2 machineguns.

However, in July 1939, Loire-Nieuport received orders for 36 LN.401 production dive bombers for the Fench Navy, and 36 LN.411 aircraft for the French Army. The LN.411 was almost identical to the LN.401, expect for the deletion of the arrestor hook, the wing folding mechanism and the emergency floatation devices. The first LN.411s were delivered in September 1939, in which month the French Air Force ordered 270 more. But in October 1939 General Vuillemin refused to accept these aircraft for the French Air Force. At this stage, with war with the USSR looking almost certain, Finland made a request that the 36 LN.411s completed for the Army and not wanted be sold to them. The French government agreed over the protests of the Navy and the aircraft were flown to Finland in November 1939 following the France-UK-Norwar-Sweden-Finland route.

They were used in combat during Winter War in dive-bombing attacks against Russian motorized columns and troop and artillery concentrations. Performance was adequate and losses were light as long as air superiority was maintained against enemy fighters. However, perhaps the greatest Ilmavoimat loss in the Wimter War occurred on 19 January 1940 when Soviet fighters broke through the Ilmavoimat fighter cover and attacked a squadron of LN.411’s, resulting in the loss of 10 out of 20 dive bombers committed, while seven of the survivors were sufficiently damaged to be no longer airworthy. However, as a dive-bomber, the remaining LN.411’s remained effective through to the end of the Winter War.

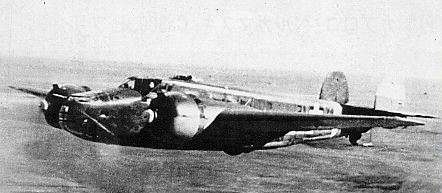

Junkers Ju87 (Stuka)

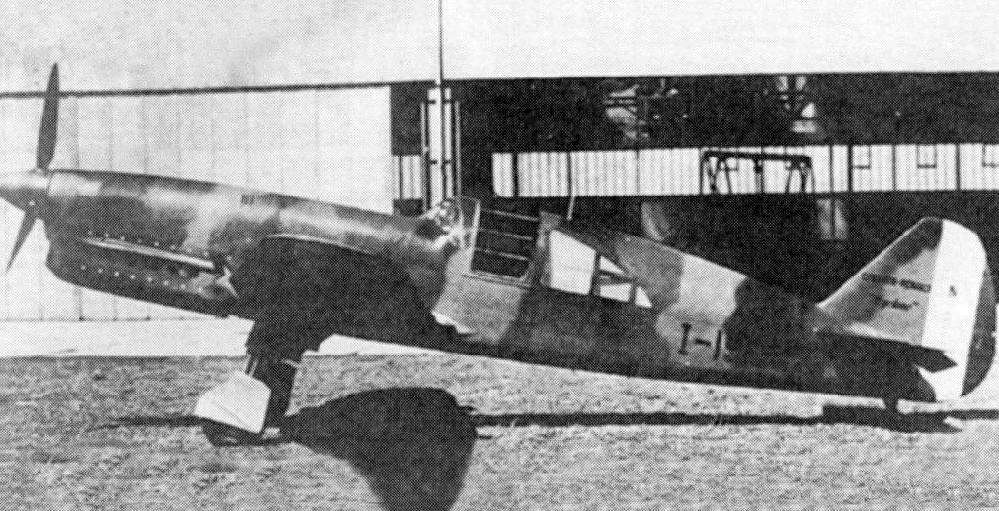

The Junkers Ju 87 or Stuka (from Sturzkampfflugzeug, "dive bomber") was a two-man (pilot and rear gunner) German ground-attack aircraft. Designed by Hermann Pohlmann, the Stuka first flew in 1935 and made its combat debut in 1936 as part of the Luftwaffe's Condor Legion during the Spanish Civil War. The Ju 87's principal designer, Hermann Pohlmann, held the opinion that any dive-bomber design needed to be simple and robust. This led to many technical innovations, like the retractable undercarriage being discarded in favour of one of the Stuka's distinctive features, its fixed and "spatted" undercarriage which, along with its inverted gull wings and its infamous Jericho-Trompete ("Jericho Trumpet") wailing siren, becoming the propaganda symbol of German air power.

The concept of dive-bombing was given a huge boost within the Luftwaffe when Ernst Udet took an immediate liking to the concept after flying the Curtiss Hawk II. When he invited Walther Wever and Robert Ritter von Greim to watch him perform a trial flight in May 1934 at the Jüterbog artillery range, it however raised doubts about the capability of the dive bomber. Udet began his dive at 1,000 m (3,800 ft) and released his 1 kg (2 lb) bombs at 100 m (330 ft), barely recovering and pulling out of the dive. The Chief of the Air Weapons Command Bureau, Walther Wever, and Secretary of State for Aviation, Erhard Milch, feared that such high-level nerves and skill could not be expected of "average pilots" in the Luftwaffe. Nevertheless, development continued at Junkers and Udet's "growing love affair" with the dive bomber pushed it to the forefront of German aviation development. Udet went so far as to advocate that all medium bombers have dive-bombing capabilities.

The design of the Ju 87 had begun in 1933 as part of the Sturzbomber-Programm. The Ju 87 was to be powered by the British Rolls-Royce Kestrel engine. Ten engines were ordered by Junkers on 19 April 1934 for £ 20,514, 2 shillings and sixpence. The first Ju 87 prototype was built by AB Flygindustri in Sweden and secretly brought to Germany in late 1934. It was to have been completed in April 1935, but, due to the inadequate strength of the airframe, construction was not completed until October 1935. However, the mostly complete Ju 87 V1 (less non-essential parts) took off for its maiden flight on 17 September 1935. The Ju 87 V1 which had a twin-tail, crashed on 24 January 1936 at Kleutsch near Dresden, killing Junkers' chief test pilot, Willy Neuenhofen, and his engineer, Heinrich Kreft. The square twin fins and rudders proved too weak; they collapsed and the aircraft crashed after it entered an inverted spin during the testing of the terminal dynamic pressure in a dive. The crash prompted a change to a single vertical stabilizer tail design. To withstand strong forces during a dive, heavy plating was fitted, along with brackets riveted to the frame and longeron, to the fuselage. Other early additions included the installation of hydraulic dive brakes that were fitted under the leading edge and could rotate 90°. The Stuka's design also included several other innovative features, including automatic pull-up dive brakes under both wings to ensure that the aircraft recovered from its attack dive even if the pilot blacked out from the high acceleration.

The RLM was still not interested in the Ju 87 and was not impressed that it relied on a British engine. In late 1935, Junkers suggested fitting a DB 600 in-line engine, with the final variant to be equipped with the Jumo 210. This was accepted by the RLM as an interim solution. The reworking of the design began on 1 January 1936. The test flight could not be carried out for over two months due to a lack of adequate aircraft. The 24 January crash had already destroyed one machine. The second prototype was also beset by design problems. It had its twin stabilizers removed and a single tail fin installed due to fears over stability. Due to a shortage of power plants, instead of a DB 600, a BMW "Hornet" engine was fitted. All these delays set back testing until 25 February 1936. By March 1936, the second prototype, the V2, was finally fitted with the Jumo 210Aa power plant, which a year later was replaced by a Jumo 210 G (W.Nr. 19310). Although the testing went well, and the pilot, Flight Captain Hesselbach, praised its performance, Wolfram von Richthofen told the Junkers representative and Construction Office chief engineer Ernst Zindel that the Ju 87 stood little chance of becoming the Luftwaffe's main dive bomber, as it was underpowered in his opinion. On 9 June 1936, the RLM ordered cessation of development in favour of the Heinkel He 118, a rival design. Apparently, Udet cancelled the RLM’s order the next day, and development continued.

On 27 July 1936, Udet crashed the He 118 prototype, He 118 V1 D-UKYM. That same day, Charles Lindbergh was visiting Ernst Heinkel, so Heinkel could only communicate with Udet by telephone. According to this version of the story, Heinkel warned Udet about the propeller's fragility. Udet failed to consider this, so in a dive, the engine oversped and the propeller broke away. Immediately after this incident, Udet announced the Stuka the winner of the development contest. Despite being chosen, the design was still lacking and drew frequent criticism from Wolfram von Richthofen. Testing of the V4 prototype (A Ju 87 A-0) in early 1937 revealed several problems. The Ju 87 could take off in just 250 m (820 ft) and climb to 1,875 m (6,000 ft) in just eight minutes with a 250 kg (550 lb) bomb load, and its cruising speed was 250 km/h (160 mph). However, Richthofen continued to push for a more powerful engine. According to the test pilots, the Heinkel He 50 had a better acceleration rate, and could climb away from the target area much more quickly, avoiding enemy ground and air defenses. Richthofen stated that any maximum speed below 350 km/h (217 mph) was unacceptable for those reasons. Pilots also complained that navigation and powerplant instruments were mixed together, and were not easy to read, especially in combat. Despite this, pilots praised the aircraft's handling qualities and strong airframe.

These problems were to be resolved by installing the Daimler-Benz DB 600 engine, but delays in development forced the installation of the Jumo 210 Da in-line engine. Flight testing began on 14 August 1936. Subsequent testing and progress fell short of Richthofen's hopes, although the machine's speed was increased to 280 km/h (173 mph) at ground level and 290 km/h (179 mph) at 1,250 m (4,000 ft), while maintaining its good handling ability. Despite teething problems with the Ju 87, the RLM ordered 216 Ju 87 A-1s into production and wanted to receive delivery of all machines between January 1936 and 1938. The Junkers production capacity was fully occupied and licensing to other production facilities became necessary. The first 35 Ju 87 A-1s were therefore produced by the Weserflug Aircraft Company Limited (WFG). By 1 September 1939, 360 Ju 87 As and Bs had been built by the Junkers factories at Dessau and Weserflug factory in Bremen.

With a crew of 2 (Pilot and Rear Gunner), the Ju87 B-2 was powered by a Junkers Jumo 211D liquid-cooled inverted-vee V12 engine, of 1184 hp / 883 kW giving a maximum speed of 242mph with a ramge of 311 miles and a service ceiling of 26,903 feet with a maximum 1,103lb bombload. Armament consisted of 2× 7.92 mm (.312 in) MG 17 machine gun forward and 1× 7.92 mm (.312 in) MG 15 machine gun to the rear while a normal bombload consisted of a single 551lb bomb beneath the fuselage.

With a crew of 2 (Pilot and Rear Gunner), the Ju87 B-2 was powered by a Junkers Jumo 211D liquid-cooled inverted-vee V12 engine, of 1184 hp / 883 kW giving a maximum speed of 242mph with a ramge of 311 miles and a service ceiling of 26,903 feet with a maximum 1,103lb bombload. Armament consisted of 2× 7.92 mm (.312 in) MG 17 machine gun forward and 1× 7.92 mm (.312 in) MG 15 machine gun to the rear while a normal bombload consisted of a single 551lb bomb beneath the fuselage.

The Ilmavoimat Procurement Team evaluated the V4 prototype (A Ju 87 A-0) of the Ju87 in the second quarter of 1937. The overall assessment following completion of the series of test flights was that aircraft lacked manoeuvrability, was slow and with a limited range and the maximum practical bombload was only 500lbs, making its effectiveness against armored battleships questionable. In addition, armored protection for the engine and crew was lacking (as it was for almost all dive bombers of the period) and the aircrafts slow speed and poor manoeuvrability meant that a heavy fighter escort would be required in order to operate effectively (again, this applied to many of the dive bombers being evaluated). Furthermore, the aircraft was still, as of early 1937, in the prototype stage and their was no guarantees that it would actually move into production.

The Ilmavoimat decided to pursue the Ju87 no further for the 1937 procurement year.

Breda BA-65 ground attack fighter

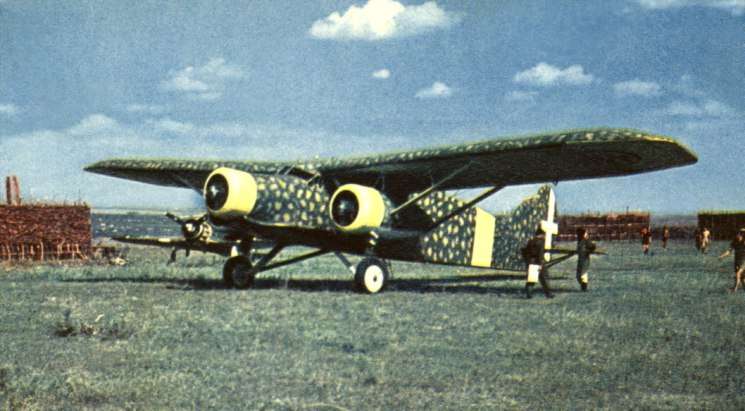

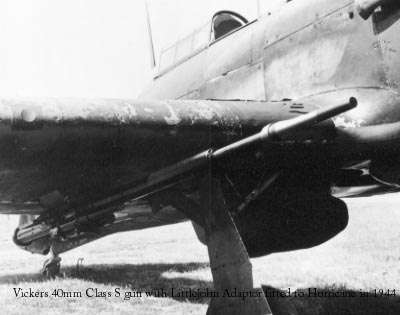

The Breda Ba.65 was a single-engine ground attack aircraft designed by Antonio Parano and Giuseppe Panzeri and was a single-seat, all-metal, cantilever low-wing monoplane with aft-retracting main undercarriage intended to undertake multiple roles as a fighter, attack and reconnaissance aircraft. The prototype, which was first flown in September 1935, like the initial production aircraft, used the 522 kW (700 hp) Gnôme-Rhône K-14 produced under license by Isotta-Fraschini.

The Ba.65 sprang from the concept of a flying military jack-of-all-trades formulated by Colonel Amadeo Mecozzi as he set about procuring a modern ground-attack plane for the Regia Aeronautica in the early 1930s. For Mecozzi, the ideal military airplane was one that would be able to perform a wide variety of functions: fighter, light bomber, army cooperation and photo- reconnaissance. Of the several designs submitted to satisfy that specification that of the Societa Italiana Ernesto Breda was ultimately selected. Developed in 1932 from the Breda 27 single-seat fighter, the Breda 64 was completed early in 1933 as a cantilever monoplane. The Ba.64 prototype was powered by a Bristol Pegasus radial engine, license-built by Alfa Romeo, in a long-chord cowling, which was later replaced by an Alfa Romeo 125 RC35 engine rated at 650 hp. The Ba.64's undercarriage retracted rearward into the wings. The open cockpit was placed well forward on the fuselage in line with the wing roots to provide an excellent field of vision down as well as forward. The headrest behind the open cockpit was extended as a streamlined fairing all the way down the fuselage upper decking to the tail. It was constructed using a frame of chrome-molybdenum tubing skinned with metal, except for fabric over the rear fuselage and control surfaces. Armament consisted of four 7.7mm Breda-SAFAT guns in the wings and up to 880 pounds of bombs in racks under the wings.

With a crew of 2, a maximum speed of 217mph, a range of 560 miles and a service ceiling of 22,965 feet, the Ba.64 was armed with 2 × 12.7 mm (.50 in) Breda-SAFAT machine guns and 3 × 7.7 mm (.303 in) Breda-SAFAT machine guns and could carry a 1200lb bombload.

With a crew of 2, a maximum speed of 217mph, a range of 560 miles and a service ceiling of 22,965 feet, the Ba.64 was armed with 2 × 12.7 mm (.50 in) Breda-SAFAT machine guns and 3 × 7.7 mm (.303 in) Breda-SAFAT machine guns and could carry a 1200lb bombload.

The basic problem with the Ba.64 was its size in relation to its power plant. With a maximum speed of 220 mph, the new aircraft lacked the performance to be a very effective attack or reconnaissance plane, let alone a successful fighter. The first production Ba.64s were delivered in the summer of 1936 and were a profound disappointment. The Ba.64's mediocre speed and heavy handling characteristics were anything but fighter like. Pilots considered them ill-equipped to undertake missions as a bomber or fighter with faults including being underpowered, heavy handling characteristics and a tendency to enter high-speed stalls that led to a number of fatal crashes. In 1937, the Ba.64s took part in a series of well- publicized military maneuvers, but they were withdrawn from service the following year. Modified into two-seaters with a 7.7mm machine gun in the rear, only a small number of Ba.64s were built for the Regia Aeronautica, since Breda was already working on an improved model, the Ba.65. Two Ba.64s were purchased by the Soviet Union in 1938. One was delivered to General Francisco Franco's Nationalist forces in June 1937 and saw brief service during the Spanish Civil War. After limited use in front-line service, the Ba.64s were relegated to second-line duties.

Evolved from the Ba.64, the Ba.65 was a single-seater intended as an interceptor and attack-reconnaissance plane. It was armed with wing-mounted armament of two 12.7mm and two 7.7mm Breda-SAFAT machine guns together with an internal bombbay for a 440-pound bomb-load in addition to external ordnance that could total 2,200 pounds. The prototype was powered by a Fiat A80 RC41 18-cylinder, twin-row radial engine with a takeoff rating of 1,000 hp. The prototype was first test-flown by Ambrogio Colombo in September 1935 and production of the Ba.65 began in 1936, the initial model having a Gnôme-Rhône 14K 14-cylinder radial of 900 hp. The single-seat Gnôme- Rhône version of the Ba.65, of which 81 were built, attained a maximum speed of 258 mph at 16,400 feet and 217 mph at sea level. Maximum cruising speed was 223 mph at 13,125 feet, and range was 466 miles with a 440-pound bomb load (rather less at 342 miles when carrying a full bomb load). The service ceiling was 25,590 feet. Starting from the 82nd aircraft, the more powerful Fiat A.80 RC.41 18-cylinder, twin-row radial engine with a takeoff rating of 746 kW (1,000 hp) engine was adopted. Production ceased in July 1939 after 218 aircraft were built by Breda and Caproni.

During the late 1930s, Italian dictator Benito Mussolini was fond of putting on impressive shows to demonstrate his country’s martial capabilities. For displaying Italian air power, his weapon of choice was the Ba.65 – the large attack bomber its hefty fuselage had a look of blunt-nosed pugnacity thanks to its single radial engine. To foreign observers prior to World War II, the Ba.65 was the dominant symbol of Italian air power. In December 1936, Mussolini, stepping beyond his effort to instill a more martial spirit in his people with propaganda flyovers, decided to give his military personnel some experience in a real conflict–the Spanish Civil War. His program to assist Franco’s Nationalists included the establishment of a 250-plane aerial contingent, the Aviazione Legionaria. The first installment of that force consisted of four Ba.65s unloaded at Palma, Mallorca, on December 28 1936, to be joined by eight more on January 8, 1937. In March, the attack planes were transported to Cádiz, along with newly arrived Fiat C.R.32 fighters, on the steamship Aerienne. The last of the Ba.65s arrived on May 3 and were formed into the 65a Squadriglia Autonoma di Assalto under the command of Capitano Vittorio Desiderio.

Teething troubles were soon experienced with the new planes, and aircraft No. 16-29 was wrecked in a landing accident. Overall though, the Ba.65s proved effective in Spain, and were compared positively with the German Junkers Ju 87. In a unique engagement, on 24 August 1936 one of the Aviazione Legionaria pilots, a Sergente Dell’Aqua, scored an air-to-air victory when he encountered a lone twin-engine Tupolev SB-2 bomber over Soria and shot it down. Of the 23 Ba.65s sent to Spain, 12 were lost in the course of the civil war. The Ba.65s flew 1,921 sorties, including 368 ground-strafing and 59 dive-bombing attacks. During operations in northern Spain, several Ba.65s were converted to two-seaters, and one was experimentally fitted with an A360 two-way radio. At the end of the campaign in October, the squadron, now commanded by Capitano Duilio S. Fanali, was transferred to Tudela in Navarra, and in December the Bredas braved bitter winter weather conditions to participate in the battles for Teruel. After that city fell, the 65a Squadriglia, bolstered by the arrival of four more Ba.65s, took part in the Aragon offensive, which by April 15 had succeeded in cutting the Spanish Republic in two. During the Nationalist advance, the Ba.65s harassed retreating Republican troops, attacked artillery batteries and landing grounds, and bombed railway and road junctions.

During the Battle of the Ebro in July 1938, the 65a Squadriglia, now under the command of Capitano Antonio Miotto, used its Ba.65s as dive bombers for the first time, striking at pontoon bridges that the Republicans had thrown across the Ebro River. By September 1938, attrition had whittled the squadron’s complement of aircraft down to eight, but six more Ba.65s arrived, and in January 1939 the squadron–again under a new commander, Capitano Giorgio Grossi–was at Logroño and ready to take part in the final offensive against Catalonia. The Ba.65s’ final mission was flown from Olmedo on March 24. When the war ended five days later, the 65a Squadriglia had logged 1,921 sorties, including 368 ground-strafing and 59 dive-bombing attacks. Of the 23 Ba.65s sent to Spain, 12 had been lost–an acceptable enough record if one discounted the relative ineffectiveness of the aerial opposition they faced most of the time. When the airmen of the Aviazione Legionaria returned to Italy in May, they bequeathed their 11 surviving Ba.65s to the Spanish Ejercito del Aire.

While the Ba.65 was being blooded over Spain, a two-seat version, the Ba-65bis, had been developed, and export orders for the Breda assault monoplane had been solicited. Fifteen aircraft with 14K engines were ordered in 1937 by the Royal Iraqi Air Force (RIAF), 13 of which were Ba.65bis two-seaters equipped with a hydraulically operated Breda L dorsal turret mounting a 12.7mm Breda-SAFAT machine gun; the remaining two were dual-control trainers. Ten single-seat Ba.65s were delivered to the Soviet Union, and in 1938, 20 Ba.65s equipped with Piaggio P.XI C.40 engines–17 single-seat attack planes and three dual-control trainers–were delivered to Chile. In 1939, 12 Ba.65bis models with Fiat A80 engines and power turrets were ordered by Portugal for its Arma da Aeronautica. In June 1937, a Ba.65 was experimentally fitted with an American Pratt & Whitney R-1830 engine in anticipation of an export order from Nationalist China that was never placed.

The Ilmavoimat evaluated the aircraft but considered it unsuitable as a dive bomber – largely due to the design which had focused on a multi-role aircraft which was not stressed for dive bombing. Again, the aircraft was not considered further in 1937.

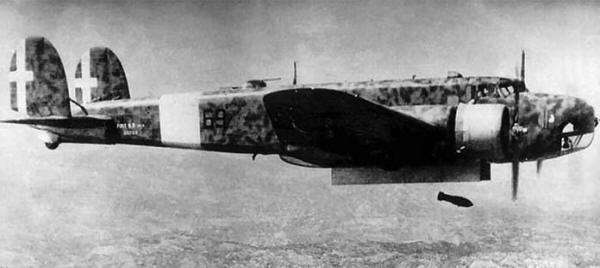

The Breda Ba.65: impressively pugnacious looking but ungainly and vulnerable to enemy fighters

The Breda Ba.65: impressively pugnacious looking but ungainly and vulnerable to enemy fighters

However, Breda Ba.65’s would be seen in Finland. In September 1939, 154 Ba.65s equipped the 101a and 102a Squadriglie of the 19o Gruppo of the 5o Stormo, the 159a and 160a Squadriglie of the 12o Gruppo, and 167a and 168a Squadriglie of the 16o Gruppo, both components of the 50o Stormo. When the Winter War broke out at the end of 1939, Italy and Mussolini were quick to express their support for Finland. And it was more than just words. While Italy sold aircraft, munitions and weapons to Finland, Mussolini was also quick to send aid above and beyond the Alpini Division that was in Finland conducting winter warfare exercises for the second year running. As was mentioned earlier, a small convoy of merchant ships accompanied the two Italian Light Cruisers sold to Finland and the merchant ships carried, among other cargo, two reinforced squadrons (12 aircraft each) of Regia Aeronautica volunteers - the 159a Squadriglia under Capitano Antonio Dell’Oro and the 160a Squadriglia under Capitano Duilio Fanali, both equipped with Breda Ba.65’s.

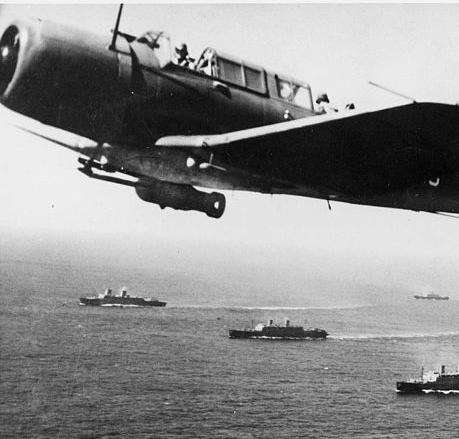

Breda Ba.65 and Pilot of the 159a Squadriglia, 12o Gruppo, 50o Stormo preparing to take off on another combat mission – late January 1940

Breda Ba.65 and Pilot of the 159a Squadriglia, 12o Gruppo, 50o Stormo preparing to take off on another combat mission – late January 1940

In combat from January 1940 and equipped with Finnish manufactured bombs, the Ba.65’s proved reasonably effective at first although vulnerable to Soviet fighters and AA fire. Steady attrition (some 50% were lost in action by the end of February 1940, primarily to AA fire), a shortage of spare parts and a realization by the Ilmavoimat that the large single-engined attack bomber was both ungainly and highly vulnerable AA fire and could only be used successfully where fighter cover and AA fire suppression was provided resulted in the phasing out of the Bredas in both the 160a and the 159a Squadriglia. The surviving aircraft were retained as ground attack trainers for a short period and were then stored for use only in an emergency situation. The heroic Italian airmen were amalgamated into a single squadron and reequipped with Blenheims from the UK that had been sold to Finland. Thus the strange situation came about where Italian Pilots flew British-supplied Blenheims while in the Middle East they fought against them.

“She climbed out of the cockpit of her Hawker Henley Dive Bomber and became instantly famous. Wearing a summer uniform of white shirt, dark tie and sleeves rolled above the elbow, she slung a parachute over her shoulder and shook out her long blonde hair. Back-lit by the afternoon sun, Ilmavoimat Ferry Pilot Maureen Dunlop looked unbelievably gamorous.”

“She climbed out of the cockpit of her Hawker Henley Dive Bomber and became instantly famous. Wearing a summer uniform of white shirt, dark tie and sleeves rolled above the elbow, she slung a parachute over her shoulder and shook out her long blonde hair. Back-lit by the afternoon sun, Ilmavoimat Ferry Pilot Maureen Dunlop looked unbelievably gamorous.”