Fire Fighting and Aerial Surveillance

As the Finnish Forestry industry expanded through the 1920’s, the early identification of forest fires became, as we have seen, an issue of greater economic importance than previously. While networks of Fire Watchtowers were built and fire patrols undertaken, a small group of aviation enthusiasts began to advocate the use of aircraft for aerial surveillance of forests in order to spot forest fires. It was a case of technology, enthusiasm and economics converging. The end of WW1 saw large numbers of war-surplus aircraft on the market. Even in Finland, somewhat isolated as it had been from the mainstream of WW1, there were young air enthusiasts in small numbers making a case for any area where aviation could be applied and where they could fly and make a living from it. And at one and the same time, the forestry industry was beginning to expand again in the aftermath of WW1. Finland was ready to take to the skies to detect forest fires.

The first steps in aerial surveillance through the 1920’s were intermittent. It is often said that Finnish aviation began during the country’s civil war of 1918, when the Finnish Air Force received its first aeroplane as a gift from the Swedish Count Rosen. But aviation, be it floating by hot air balloon, flying a model aeroplane, gliding a sailplane or soaring in a motorized aircraft, was practised long before. The early annals of Finnish flight contain the names of numerous aviators whose efforts and sacrifices, successes and failures and above all, their burning passion for flight, paved the way for the development of aviation at the beginning of this century and onwards to the present day. One such aviator in the early 1920’s was Baron Kaspar Fabian Wrede of Elima. Kaspar Wrede was born on October 24, 1892 to a family of the “old” nobility. His parents were the District Judge, Baron Kasper Hjalmar Wrede and Anna Sophia Ihre of a Swedish noble family. In 1911, Kaspar and his 13 year old brother had built a hang glider neaf Turku which, pulled by a horse, rose to 5-6 meters above ground and glided “for significant distances.”

Kaspar Wrede graduated from the Helsinki Swedish Lyceum in 1913 and then studied at the Dresden University of Technology, Mechanical Engineering Department from 1913 to 1914. Wrede joined one of the first set of Jaeger volunteers who undertook military training in Germany and whose goal was the independence of Finland from RussiaHe enrolled on the 25 February 1915 and was placed in 1 Komppaniaan, but he was released from service due to illness on 15 April 1915. Returning home to Finland to convalesce, in 1915, he had flown a home-made monoplane of the ice of the Kymijoki river. In 1916, Kaspar Wrede travelled to Sweden and studied flying at the Thulin Ljungbyhed flight school. Later in 1916, he traveled to the United States and went to work in the Curtiss aircraft factory in Buffalo. At the same time, he continued his flying studies at the Newport News Airport over 1917-1918 and on 21 February 1917 the Aviation Club of America awarded him what was apparently the first Finnish International Airplane Pilot Certificate No. 661 This certificate was conditional on a test flight that was carried out in a Curtiss JN-4 aircraft.

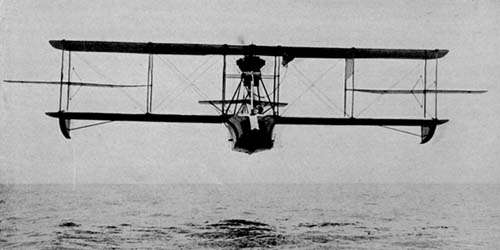

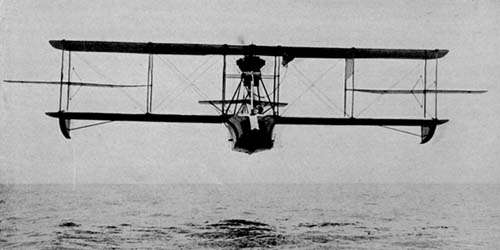

Wrede returned to Finland in the autumn of 1918, after the civil war. He then served in the Finnish Army, was promoted to Sergeant on 12 October 1918, and was placed in the Hermanni flight department. He became a mechanic and later served for a short period in the Maintenance Unit at Utti airport, where he worked for a short time. He resigned from the army on 16 January 1919. His family had interests in the Forestry Industry and in April 1919 Wrede purchased a Curtiss Flying Boat and in May, after a number of familiarization flights, he made an initial flight in order to demonstrate the viability of using aircraft in fire surveillance. The Head of the State Forest Service offered to hire him but Wrede refused pay, saying that he wanted only the expenses of the aircraft reimbursed together with a salary of “many thanks.” Wrede flew almost daily in July and August 1919 as a flying fire warden over the forests of Eastern Karelia.

Kaspar Wrede’s second-hand Curtiss Flying Boat

Kaspar Wrede’s second-hand Curtiss Flying Boat

Kaspar Wrede (seated) in the Curtiss hydroplane he used to spot forest fires, 1921

Kaspar Wrede (seated) in the Curtiss hydroplane he used to spot forest fires, 1921

News of Wrede’s work quickly spread; Finnish Forestry magazine had an article about it in their September 1919 issue. However, among some foresters, reviews of the tool were mixed. The trial continued through the 1920 fire season but not as many fires were first spotted by the air patrol as had been hoped, and the lack of wireless radios for communication between pilot and ground crew slowed the fire reporting process down significantly. In addition, the Curtiss Flying Boat itself was a bit of a problem. While it provided the pilot with an excellent panoramic view, it had serious drawbacks, being notoriously unreliable and it was also not an easy plane to handle. The engine broke down regularly, forcing emergency landings on the closest body of water. If the engineer (who always accompanied the pilot) couldn't fix the problem, the crew had to walk out of the bush to get help - unless they had a messenger pigeon or a wireless transmitting set on board. It also needed lots of room to manoeuver - to take off, gain altitude, and descend. This left a very narrow margin for error in mountainous, or even hilly country. By the end of the flying season the H-Boat was waterlogged and unwieldy, since the wooden hull steadily absorbed water over the summer.

In September 1920, after a two-season trial, the Head of the Forest Service ended the program as not having proved itself particularly useful, and the Forest Service went on to concentrate on the Fire Tower construction program. Disappointed, Wrede sold his aircraft and traveled to Australia. He went on to rent a deserted island in Fiji, where he died on 16 October 1921 from a serious and hitherto undiagnosed illness. Thus, the first Finnish experiments in aerial fire surveillance ended – but they were not forgotten and would be resurrected a decade later. And as with many other initiatives, the resurrection in this case was sparked off by experiments being undertaken in the USSR.

Intermittent experiments in the use of aircraft in Finland took place of and on through the late 1920’s, when Ilmavoimat aircraft were occasionally used to patrol and detect forest fires. At this time also, various attempts were made to drop water and primitive foam mixtures on fires, using such devices as five-gallon cans, paper bags, and wooden beer kegs attached to parachutes. These early experiments met with little success but sporadic experiments with fire retardents continued and aerial surveillance did continue. During this same period, occasional non-emergency parachute jumps were being made by the military and a few thrill-seeking barnstormers.

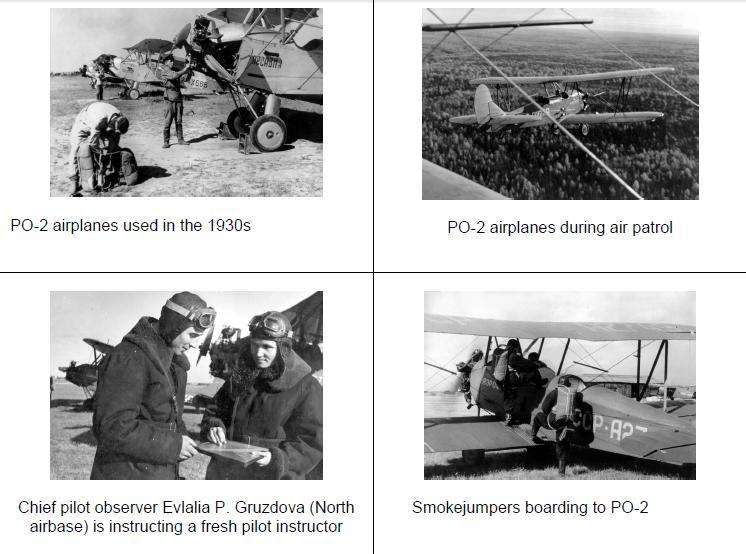

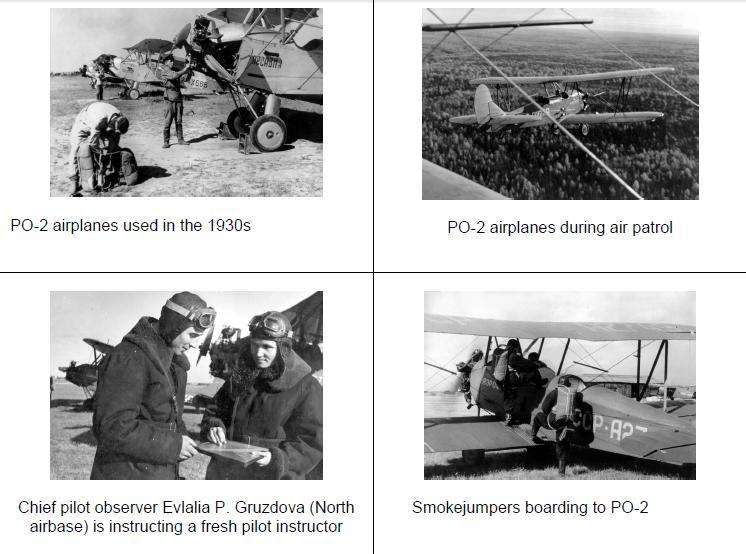

However, as in so many other areas, Finland received a real and sharp impetus from events in the USSR. In 1931, the USSR had set up the Avialesookhrana organisation, an aerial patrol organisation for forest protection responsible for patrolling some 1.5 million hectares in the Nizhni Novgorod Province. The first group of Forest Engineers were trained as Pilot Observers and in that year 40 hours flying was logged, with some 16 fires detected. From 1932 to 1935 research on the use of aviation in forestry was conducted by the Leningrad Branch of the All-Union Research Institute of Agriculture and Forest Aviation. Furthermore, in 1934, the same institute started a project to investigate the feasibility of using parachutes in fighting forest fires. A number of tests were carried out on the delivery of both equipment and people to the sites of forest fires by air. In 1935, a team of three fire-fighters under the leadership of G.A. Mikeev carried out 50 parachute jumps for forest fire suppression from a U-2 (PO-2) aircraft using the PT-1 model parachute.

Soviet Avialesookhrana Aircraft, Patrols and Smokejumpers – 1930’s: In 1936 the Leningrad Branch of the All-Union Research Institue of Agriculture and Forest Aviation was reorganized into the State All-Union Trust of Forest Aviation (VGTLA) based in Leningrad. P. A. Tsetlin was appointed head of the organisation and all activities relatred to aerial forestry fire protection throughout the USSR were placed under the control of VGTLA. An Air Services Department was formed, with four Forest Aviation Detachments – Leningrad (headed by M.D. Artamonov), Northern (headed by V. S. Rekunov), Krasnoyarsk (headed by A. T. Hramtsov) and Tyumen (headed by S.Z. Beloborodin). These detachments were responsible for aerial forest fire protection, assisting with wood floating, aerial photography of forest resources, providing transportation and communications and carrying out general forest aviation functions. The areas patrolled and the number of flight hours grew rapidly and by 1939 the areas covered had increased by more than 45 times, reaching 95 million hectares, and the flight time logged had increased to 7,200 hours. The number of aircraft involved, primarily the PO-2, had climbed to approximately 110 overall.

Soviet Avialesookhrana Aircraft, Patrols and Smokejumpers – 1930’s: In 1936 the Leningrad Branch of the All-Union Research Institue of Agriculture and Forest Aviation was reorganized into the State All-Union Trust of Forest Aviation (VGTLA) based in Leningrad. P. A. Tsetlin was appointed head of the organisation and all activities relatred to aerial forestry fire protection throughout the USSR were placed under the control of VGTLA. An Air Services Department was formed, with four Forest Aviation Detachments – Leningrad (headed by M.D. Artamonov), Northern (headed by V. S. Rekunov), Krasnoyarsk (headed by A. T. Hramtsov) and Tyumen (headed by S.Z. Beloborodin). These detachments were responsible for aerial forest fire protection, assisting with wood floating, aerial photography of forest resources, providing transportation and communications and carrying out general forest aviation functions. The areas patrolled and the number of flight hours grew rapidly and by 1939 the areas covered had increased by more than 45 times, reaching 95 million hectares, and the flight time logged had increased to 7,200 hours. The number of aircraft involved, primarily the PO-2, had climbed to approximately 110 overall.

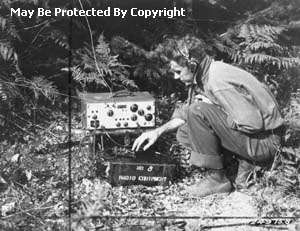

In 1931, aware of the experiments in the USSR and also kept up to date on similar experiments in both the USA and Canada, the State Forest Service decided to conduct further experiments with aerial fire surveillance. A number of criteria were decided on, largely based on the North American experience. Most important was that detection aircraft should provide excellent visibility, be reliable, and handle well at slow speeds. Visibility was particularly important. Fire observers needed a wide, unbroken view of the land below, in order to spot that thin spiral of smoke that signals a fire. When a fire was spotted, the detection aircraft slowly circled over the fire. The observer would take a good look at the fire behaviour, note the closest source of water, and estimate the number of firefighters and the equipment needed to put it out. Within a year or two, the Forest Service would experiment extensively with air-to-ground wireless transmission, but in the first two years no patrol planes carried wireless equipment.

Planes without wireless followed these procedures.

Detection. When the observer detected a smoke, he passed a note to the pilot, or pointed. The roar of the engine made normal conversation impossible.

Information. The pilot flew to the spot and circled over the fire, while the observer plotted the location on a map. He studied the fire carefully, noting fire location, size, and rate of spread; timber type; topography; access routes; available water; and the equipment and numbers of fire fighters required.

Communication. Once the observer located the fire and sized it up, he had to get the information to headquarters as fast as possible. There were several options:

- Drop a message bag over forestry headquarters;

- Relay the message from a telephone or telegraph station, if the pilot could readily locate a nearby lake to land on;

- Use a portable phone, a time-consuming task. First, the pilot located a suitable lake to land on, close to a telephone line. Then the observer headed out on foot to the line. He threw a phone wire over the line to make contact, shouted into the phone until someone heard him, and reported the fire.

Reporting wildfire using these methods was not always 100% reliable, but it was incomparably faster than ground patrols.

State Forest Service patrol planes flying in close formation, Eastern Karelia, 1933.

State Forest Service patrol planes flying in close formation, Eastern Karelia, 1933.

The aircraft used in aerial fire surveillance over 1931-1933 were all borrowed from the Ilmavoimat – which loaned the Forest Service half a dozen IVL A.22 Hansa’s – while as a floatplane the aircraft was suitable, the Hansa was also a low-winged monoplane which was somewhat limiting in terms of visibility. After the first two seasons, with over 400 major fires detected and put out before they could do significant damage, and numerous smaller fires spotted and quickly put out bt fire response teams, the Forest Service declared the program a success and in 1933, the State Forest Service went ahead and purchased six De Havilland Moths which were fitted with floats on delivery. The Moth was light and maneuverable, reliable, and did not require the services of an in-flight engineer. On the Moth, the pilot doubled as the fire observer and everyone who flew the aircraft loved the Moth. According to one, it took to the air 'like a homesick angel'. The Moth went on to fly on fire patrols until the 1940s.

De Havilland Gypsy Moth floatplane – the State Forest Service used aircraft that were largely identical to the aircraft in this photo

De Havilland Gypsy Moth floatplane – the State Forest Service used aircraft that were largely identical to the aircraft in this photo

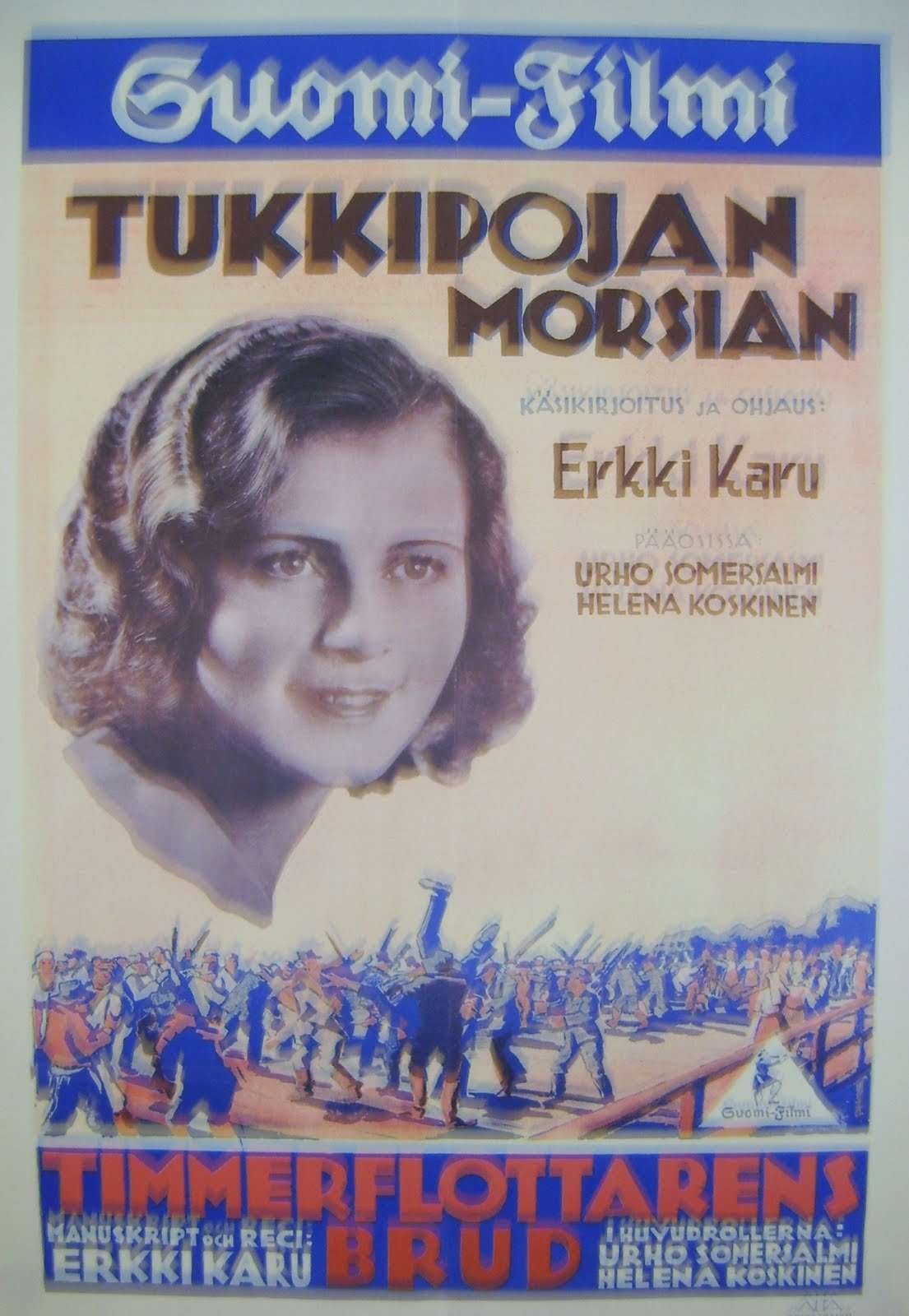

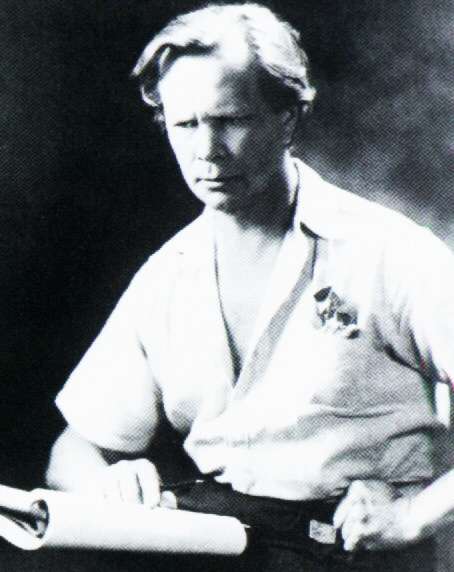

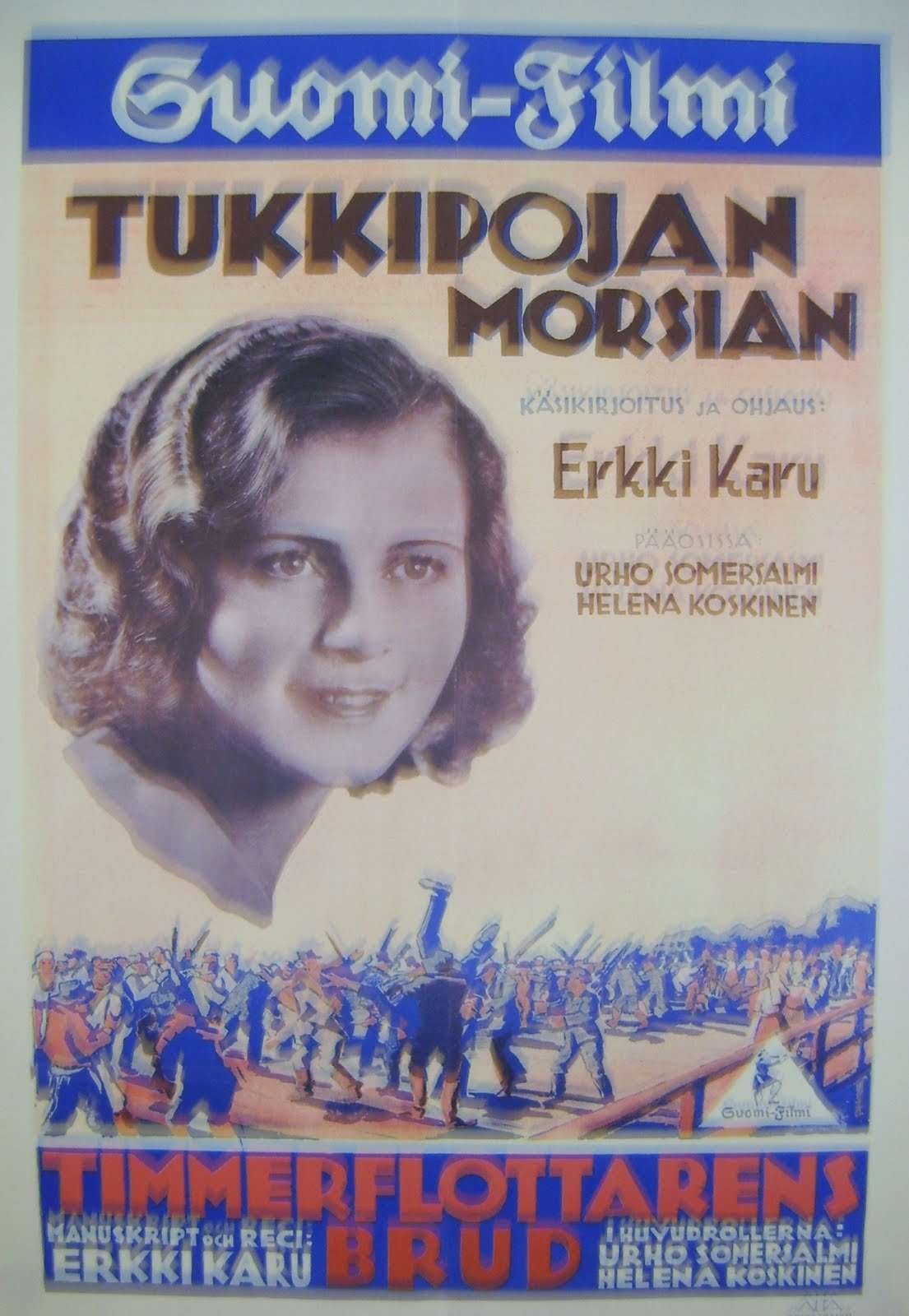

The rumor that each Forest Service aircraft was equipped with a telescope and machine gun (which probably originated from the early use of the Hansa’s by the Forest Service) laos proved a powerful deterrant to arson and to timber theft. (An interesting cultural theme of the 1920’s and 1930’s was the popularity of books and films about logging – an early example being Erkki Karu’s 1923 film, “The Logroller’s Bride” with superb cinematography by Jäger and Oscar Lindelöf. A later movie was “Tukkijoella” (Log River – 1928). Films of this genre gave the Finnish cinema and the viewing public one of its most popular characters – the lumberjack (tukkijatka, tukkipoika, tukkilainen) who at his most heroic hour becomes the log-roller or the shooter of rapids (koskenlaskija). The significance of this character in Finnish cinema is comparable to that of the Cowboy on American cinema. He is the pioneer, the wandere, the adventurer. He negotiates the frontier, he is an embodiment of the conflict between wilderness and civilization. We meet this figure in “Koskenlaskijan Morsian” (The Logroller’s Bride), 1922, remade 1937), “Tukkijoella” (Log River, 1928 – remade 1937 and 1951) and in “Tukkipojan Morsian” (The Lumberjack’s Bride, 1931) as well as in others.

Poster for Tukkijoella

Poster for Tukkijoella

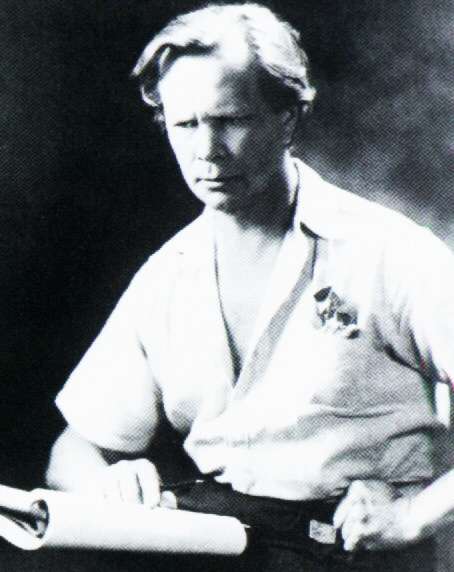

Erkki Karu

Erkki Karu,

founder of Suomen Filmikuvaamo (later to become Suomi-Filmi) and then Suomen Filmiteollosuus: He also directed the most important films of the era and was the prime figure of Finnish cinema before his early death in 1935. His “The Village Shoemakers” (1923) is the essential silent masterpiece, a freshly told folk comedy after Aleksis Kivi's play with mildly experimental camerawork by German Kurt Jäger. Other notable films by Karu include: Koskenlaskijan Morsian (The Logroller's Bride) (1923), with superb cinematography by Jäger and Oscar Lindelöf, and also the first Finnish film distributed widely abroad; When Father Has Toothache (1923), a short and surrealistic farce; and Our Boys (1929), a patriotisic forerunner of many military farces. Audiences of the agricultural country were affected by Suomi-Filmi's rural subjects. Dealing with deeply national countryside stories remained as company's policy through the silent era. Occasionally there were some attempts to make more urban, or more "European" films like Karu's Summery Fairytale (1925), but the public stayed away. Another important director at Suomi-Filmi was Puro, who made the company's first feature “Olli's Years of Apprenticeship” (1920) and one of the few Finnish horror films, “Evil Spells” (1927). An interesting oddity of the last two silent years was Carl von Haartman, a soldier and an adventurer, who had worked as a military advisor in Hollywood. Because of this he was considered capable of directing films. His two upper-class spy dramas, The Supreme Victory (1929) and Mirage (1930), were quite passable, but didn't attract the public. We will see more of Carl von Haartman as this Winter War history progresses….

Poster for “Tukkipojan Morsian” (The Lumberjack’s Bride, 1931).

Poster for “Tukkipojan Morsian” (The Lumberjack’s Bride, 1931).

And a Poster from a later remake of Tukkijoella

And a Poster from a later remake of Tukkijoella

In the mid-1930’s, the State Forest Service also contracted aircraft from Veljekset Karhumäki for aerial fire surveillance patrols and also for aerial mapping. It was through these contracts that the State Forest Service became aware of the Noorduyn Norseman, first introduced into Finland in July 1937 by Veljekset Karhumäki. Impressed by the aircraft, the State Forest Service’s Aerial Surveillance and Fire Fighting Unit purchased eight Norseman aircraft from Noorduyn towards the tail end of 1937, taking delivery in 1938 in time for the start of the Fire Season. Originally designed and constructed to handle the harsh flying conditions of the Canadian bush, the Norseman was not intended to be a detection plane but was to be used as a reliable, all-purpose utility machine, a “half-ton truck with wings”. The Norseman had phenomenal STOL: short take-off and landing capabilities and this capability made all the difference on loaded fire patrols carrying firefighters and equipment. Even on a small lake, or in a tight spot, a heavily loaded Norseman needed very little room to land, or to take off. (Incidentally, the eight Norseman purchased by the State Forest Service, together with Veljekset Karhumäki’s five and the Ilmavoimat’s twenty five, gave the Ilmavoimat thirty eight of these very useful utility aircraft as of the start of the Winter War. Able to carry 10 passengers each and with a range of 810 nautical miles, thirty five of these aircraft gave a significant air-lift capability to the Finnish military all on their own).

State Forest Service Noorduyn Norseman flying through mountains on the Norwegian Border – near the Finnmark

State Forest Service Noorduyn Norseman flying through mountains on the Norwegian Border – near the Finnmark

State Forest Service Fire Surveillance Patrol utility aircraft: Transferring fire equipment from a fire truck to a utility aircraft. Use of the utility aircraft greatly speeds up the transportation of equipment and supplies. The Norseman aircraft can carry 10 men and equipment into fires for initial attack thus saving many hours of time necessary to cover the same distances by boat, portage & hiking. Arriving at a fire soon after it starts means that often the fire can be put out while it is still small.

State Forest Service Fire Surveillance Patrol utility aircraft: Transferring fire equipment from a fire truck to a utility aircraft. Use of the utility aircraft greatly speeds up the transportation of equipment and supplies. The Norseman aircraft can carry 10 men and equipment into fires for initial attack thus saving many hours of time necessary to cover the same distances by boat, portage & hiking. Arriving at a fire soon after it starts means that often the fire can be put out while it is still small.

State Forest Service patroller checking a fire cache on an island. The availability of utility aircraft meant added capability for the fire fighting teams responsible for fighting forest fires.

State Forest Service patroller checking a fire cache on an island. The availability of utility aircraft meant added capability for the fire fighting teams responsible for fighting forest fires.

Forest Fire Fighting Noorduyn Norseman dropping fire tools near a fire

Fire Fighting and the Origins of the Forest Service Smokejumpers (Savusukeltaja)

Forest Fire Fighting Noorduyn Norseman dropping fire tools near a fire

Fire Fighting and the Origins of the Forest Service Smokejumpers (Savusukeltaja)

Over the early 1930’s the use of aircraft for Fire-Spotting over the summer months proved effective, with a large number of fires in remote areas being spotted, enabling teams to be dispatched to get them under control. With the emphasis on a fire exclusion policy (complete fire suppression) in forests nationwide, improvements were being continually made to firefighting tools and techniques. However, forest fire fighting teams still had to hike for miles into a fire area with heavy equipment and then work frantically to fight the fire once they arrived on the scene. They would dig trenches or cut fire lines to clear an area down to the soil. By leaving nothing to fuel the advancing fire, they hoped to keep the fire from spreading further. In the early days these “firefighters” were any men the Forest Service could recruit to work and it often took long periods of time for the firefighters to hike to fires. And despite this, some fires nevertheless did get out of control before the teams could get there.

With larger passenger aircraft now flying regularly around Finland, in early 1935 Erik Rasmussen, head of the Forest Services Fire Fighting Department received a proposal from one of the Regional Fire Fighting Teams proposing that Forest Fire Fighters be parachuted in to remote fires as a means to provide a much quicker initial response. By parachuting in, self-sufficient firefighters could arrive fresh and ready for the strenuous work of fighting fires in rugged terrain. The Forest Services Fire Fighting Department asked for advice from the Ilmavoimat, who responded that “….parachuting into forests is dangerous and impractical and should not be attempted other than as an emergency measure….” However, after meeting with the Team that had proposed the technique, who almost unanimously were strongly in favor of giving it a go, Rasmussen went ahead and authorized an experiemental program which began in early 1934. Much time was spent on the development of special parachutes and equipment, with the first actual jumps made in the summer of 1935. Pictured below is the first team of Forest Service Fire Fighting Parachutists.

The first team of Finnish Forest Service Fire Fighting Parachutists – Summer 1935

The first team of Finnish Forest Service Fire Fighting Parachutists – Summer 1935

The first jumps were made from whatever aircraft were available. The first team consisted of eleven fire fighters, all of whom were self-taught. As Henrik Garvar, a founding member of the first Savusukeltaja team and one of the first ParaJaegers - and who would later go on to command a ParaJaeger Battalion by the end of the Winter War, recollected in his biography, “

Savusukeltaja” (Smokejumpers) (Otava, Helsinki, 1951), “Our training consisted of our Team Leader saying: ‘This is your parachute. You know what a fire is. We jump tomorrow.” We were all volunteers of course, and we all jumped. Later, we developed a training program but to start with, it was all self-taught and we had some problems we hadn’t really thought about too well. Like how to get down if you got hung up in a tree.”

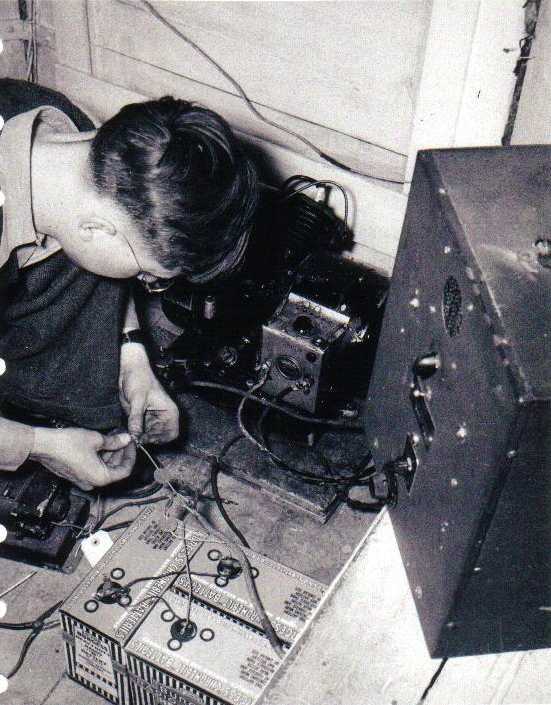

Equipment was almost all hand-made with the exception of the Parachutes. Here, a member of the first Fire Fighting Parachutist Team, suited up in a complete Fire Fighter-Parachutist's outfit, Summer 1935.

Equipment was almost all hand-made with the exception of the Parachutes. Here, a member of the first Fire Fighting Parachutist Team, suited up in a complete Fire Fighter-Parachutist's outfit, Summer 1935.

Savusukeltaja taking a last glance at his objective before leaving the plane. Note right hand gripping ripcord. (Reflection shows in plane window).

Savusukeltaja taking a last glance at his objective before leaving the plane. Note right hand gripping ripcord. (Reflection shows in plane window).

The view from inside the aircraft as the Savusukeltaja prepare to jump

The view from inside the aircraft as the Savusukeltaja prepare to jump

Forest Service Fire-Fighter–Parachutist about to leave the plane on his descent to a small forest fire. Note right hand gripping ripcord.

Forest Service Fire-Fighter–Parachutist about to leave the plane on his descent to a small forest fire. Note right hand gripping ripcord.

Forest Service Fire-Fighter–Parachutist has jumped but not yet pulled the Ripcord. All jumpers used Ripcords – Static Lines were not used. Given that jumping was from a fairly low height to avoid drifting away from the fire, this added a further element of risk to what was an already hazardous occupation

Forest Service Fire-Fighter–Parachutist has jumped but not yet pulled the Ripcord. All jumpers used Ripcords – Static Lines were not used. Given that jumping was from a fairly low height to avoid drifting away from the fire, this added a further element of risk to what was an already hazardous occupation

Forest Service Fire-Fighter–Parachutist soon after leaving plane with the pilot 'chute completely distended and the 30-foot canopy unfolding.

Forest Service Fire-Fighter–Parachutist soon after leaving plane with the pilot 'chute completely distended and the 30-foot canopy unfolding.

Forest Service Fire-Fighter – Parachutist immediately after leaving plane before parachute is completely distended. Forest fire is at lower left.

Forest Service Fire-Fighter – Parachutist immediately after leaving plane before parachute is completely distended. Forest fire is at lower left.

Aerial view of wildfire, smoke columns with Forest Service smokejumpers with parachutes on ground.

Aerial view of wildfire, smoke columns with Forest Service smokejumpers with parachutes on ground.

Forest Service Fire-Fighter – Parachutists dropping towards the fire. The aircraft used in these photos was a chartered Ford Trimotor.

Forest Service Fire-Fighter – Parachutists dropping towards the fire. The aircraft used in these photos was a chartered Ford Trimotor.

With hand tools, explosives, and the ability to think fast on their feet, Forest Service Fire-Fighter Parachutists had one job – to contain the fire they were dropped to extinguish. First, they had to get there by parachuting into often unchartered territory and treacherous forests and hills – with the risk of dropping into a lake or river to contend with as well. Often, they were the only hope to stop a fire burning out of control, and they rapidly became the most important line of defense against one of the deadliest of natural disasters. Success meant saving valuable forests, but failure could mean losing lives, property and millions of dollars in damage.

With a successful first season, the Forest Service Fire-Fighter Parachutists expanded rapidly and for the 1936 Fire Season, some 250 forest fire fighters were trained in parachuting techniques. By this time, the first team had set up a training program based on their experiences over the first season, and budding Fire-Fighter Parachutists were recuited and trained early on, before the high-risk fire season period started. They rapidly became a news story, with papers carrying headline stories about the courageous “Savusukeltaja” and their exploits in fighting fires in the depths of the remote forests.

The first Smokejumper Base; ca. 1937. Building on the left is the parachute maintenance building (loft not visible). The middle building is the accommodation barracks. The building on the right is the fire-fighting equipment cache.

The first Smokejumper Base; ca. 1937. Building on the left is the parachute maintenance building (loft not visible). The middle building is the accommodation barracks. The building on the right is the fire-fighting equipment cache.

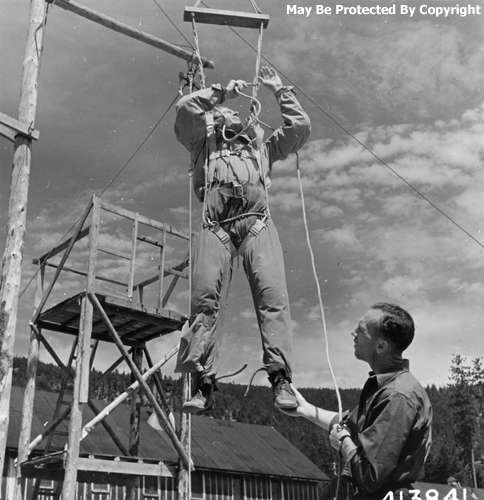

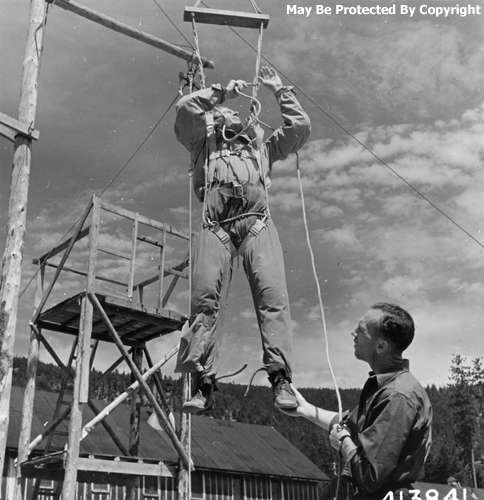

Early Parachute Training simulator, designed and built by the first Forest Service Fire-Fighter Parachutist Team. Smokejumper trainees learnt the control, feel and turning characteristics which closely simulated those of smokejumper parachutes.

Early Parachute Training simulator, designed and built by the first Forest Service Fire-Fighter Parachutist Team. Smokejumper trainees learnt the control, feel and turning characteristics which closely simulated those of smokejumper parachutes.

A Forest Service Fire-Fighter Parachute Instructor-Rigger instructing a prospective smokejumper in the use of a "drop rig". This simulated landing when a chute was caught in a snag or other obstacle and trained the candidate in the use of a landing rope.

A Forest Service Fire-Fighter Parachute Instructor-Rigger instructing a prospective smokejumper in the use of a "drop rig". This simulated landing when a chute was caught in a snag or other obstacle and trained the candidate in the use of a landing rope.

A trainee Smokejumper leaving a 30-foot platform used for training jumps.

A trainee Smokejumper leaving a 30-foot platform used for training jumps.

A trainee Smokejumper leaving a 30-foot platform used for training jumps.

A trainee Smokejumper leaving a 30-foot platform used for training jumps.

1936 Smokejumpers – this Team was the first to graduate from the Smokejumpers School in 1936. This particular team, led by Henrik Garvar, made up largely of Suojeluskuntas members, were also the first soldiers in the Maavoimat to parachute into a military exercise and all those pictured here went on to become founding members of the first Maavoimat experimental Parajaeger unit – the forerunner of the Parajaegerdivisoona.

1936 Smokejumpers – this Team was the first to graduate from the Smokejumpers School in 1936. This particular team, led by Henrik Garvar, made up largely of Suojeluskuntas members, were also the first soldiers in the Maavoimat to parachute into a military exercise and all those pictured here went on to become founding members of the first Maavoimat experimental Parajaeger unit – the forerunner of the Parajaegerdivisoona.

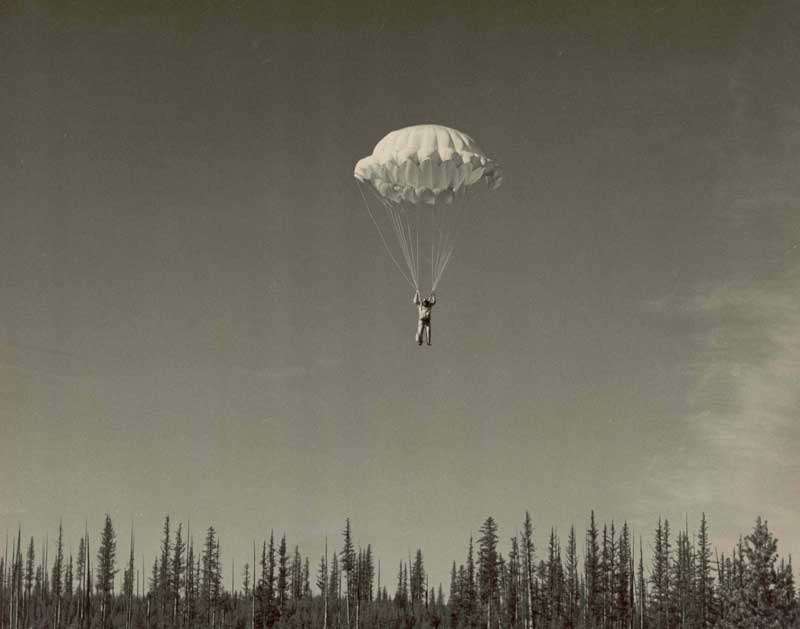

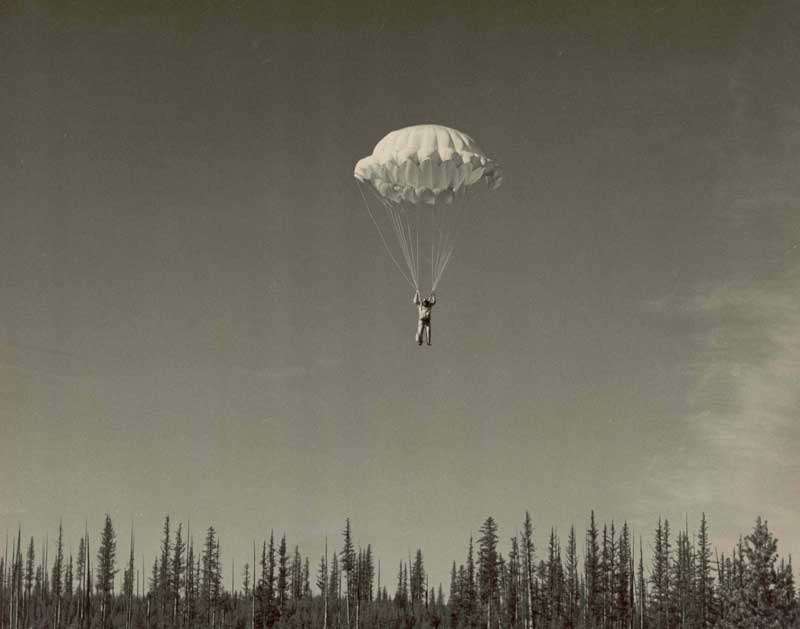

Unlike the first Smokejumpers, who learnt on the job by parachuting straight into the forest, subsequent Smokejumpers got to learn by jumping into clear areas that were obstacle-free

Unlike the first Smokejumpers, who learnt on the job by parachuting straight into the forest, subsequent Smokejumpers got to learn by jumping into clear areas that were obstacle-free

This made learning a little less dangerous

This made learning a little less dangerous

A Safe Landing… Henrik Garvar showing the “newbies” how it’s done

A Safe Landing… Henrik Garvar showing the “newbies” how it’s done

And a more typical tree landing encountered by Forest Service smokejumpers. The Smokejumper has released risers from the shoulder snaps of his harness, and has lowered himself approximately 6 feet down by means of the 75-foot let-down rope carried for this purpose in the leg pocket of the jumper's suit.

And a more typical tree landing encountered by Forest Service smokejumpers. The Smokejumper has released risers from the shoulder snaps of his harness, and has lowered himself approximately 6 feet down by means of the 75-foot let-down rope carried for this purpose in the leg pocket of the jumper's suit.

April 1937: Chute near top of 125 foot Douglas fir where it was purposely guided by the jumper (Henrik Garvar demonstrating again…) as a demonstration for Candidate Smokejumpers. The Canopy is caught on branches ten feet below the tip. The Jumper descended on his rope with relatively little difficulty.

April 1937: Chute near top of 125 foot Douglas fir where it was purposely guided by the jumper (Henrik Garvar demonstrating again…) as a demonstration for Candidate Smokejumpers. The Canopy is caught on branches ten feet below the tip. The Jumper descended on his rope with relatively little difficulty.

A Smokejumper in a rather more difficult but not unusual situation on landing

A Smokejumper in a rather more difficult but not unusual situation on landing

Savusukeltaja, suited up, loading into Ford Tri-Motor.

Savusukeltaja, suited up, loading into Ford Tri-Motor.

Savusukeltaja in a Ford Trimotor plane about to jump. This practice jump is being made with a static line, which became the preferred technique by the late 1930’s, and which went on to become adopted by the Maavoimat’s ParaJaegers. Note webbing on the parachute which is hooked by a snap catch to a wire line stretched at the side of the doorway.

Savusukeltaja in a Ford Trimotor plane about to jump. This practice jump is being made with a static line, which became the preferred technique by the late 1930’s, and which went on to become adopted by the Maavoimat’s ParaJaegers. Note webbing on the parachute which is hooked by a snap catch to a wire line stretched at the side of the doorway.

Savusukeltaja descends with his parachute, nearing the tops of the trees. This photo from Erkki Karu’s 1938 film “Savusukeltaja”. The film made the term a household word and did much to make the newly forming ParaJaegerdivisoona a much sought after unit by young conscripts. The image of the “Savusukeltaja”more or less overwhelmed the inherent Finnish dislike for authority and being told what to do that made conscript service undesirable for many young Finnish men. The ParaJaegerdivisoona would go on to capitalize heavily on the“Savusukeltaja”image with young men from the rural areas.

Savusukeltaja descends with his parachute, nearing the tops of the trees. This photo from Erkki Karu’s 1938 film “Savusukeltaja”. The film made the term a household word and did much to make the newly forming ParaJaegerdivisoona a much sought after unit by young conscripts. The image of the “Savusukeltaja”more or less overwhelmed the inherent Finnish dislike for authority and being told what to do that made conscript service undesirable for many young Finnish men. The ParaJaegerdivisoona would go on to capitalize heavily on the“Savusukeltaja”image with young men from the rural areas.

Savusukeltaja at end of descent about to free himself from chute, remove protection suit, and start for fire. Much of his equipment is similar to that used at the battlefronts, since he encounters many of the same perils.

Savusukeltaja at end of descent about to free himself from chute, remove protection suit, and start for fire. Much of his equipment is similar to that used at the battlefronts, since he encounters many of the same perils.

The Forest Service Savusukeltaja pioneered the way for military parachuting within Finland. From their early origins, they went on to develop the techniques, parachuting equipment and training that the Maavoimat’s ParaJaegerdivisoona would go on to adopt and adapt. They would also pioneer and test variations in parachute design. The first Maavoimat ParaJaeger units started from a core of Forest Service Fire-Fighter Parachutists who went on to teach volunteers from the Maavoimat combat parachuting skills. When we come to look at the Maavoimat in detail, we will further examine the evolution, structure and training of the Maavoimat’s ParaJaeger units.

Next: Radios and Waterbombers....