Aid and Assistance from France (continued)

Arms and Artillery from France

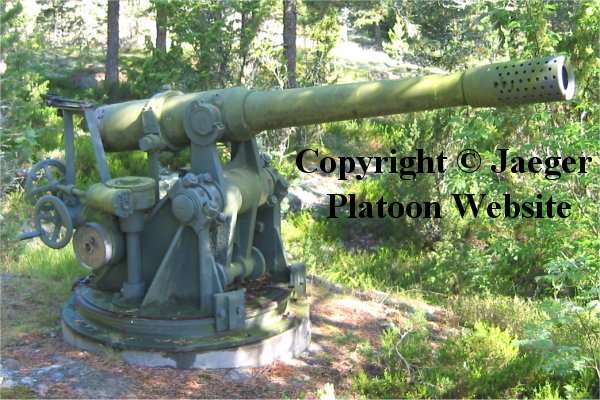

And a note: thanks to http://www.jaegerplatoon.net and Jarkko for much of the information on, and photos of, the actual guns. All the alternative history around them is of course, mine.

Well prior to both the Winter War and the Defence Budgets of the 1930’s, the Maavoimat decided to test new and modern French field guns for possible further acquisitions intended to build up the Maavoimat’s artillery strength. To this end, four French Schneider-manufactured 76 K/22 (76 mm Cannon Model 1922) were purchased and arrived in 1926. Designed by Schneider in the early 1920’s, France didn't buy any as it had an enormous stock of surplus Canon de 75 modèle 1897 field guns on hand and as a result, the Schneider 76 mm Cannon Model 1922 was offered for export.The test guns were French export models manufactured specifically in 76.2-mm x 385R calibre for Finland, so they could use the same ammunition as the 76 K/02. The weight of the gun was 1,320kgs, maximum range was 12,000 meters, calibre was 76mm, shell weight was 4.82 to 6.35kgs.

Photo sourced from: http://www.winterwar.com/images/GunsWrecoil/76k22c.jpg

The Schneider-manufactured 76 K/22 (76 mm Cannon Model 1922)

Photo sourced from: http://www.winterwar.com/images/GunsWrecoil/76k22c.jpg

The Schneider-manufactured 76 K/22 (76 mm Cannon Model 1922)

In addition, four St Chamond-manfactured guns in the same calibre, the model 76 K/23 (St. Chamond 76mm cannon model 1923) were bought for evaluation in 1926. This gun failed to meet expectations and no more were bought. The main weakness was that the carriage was too weak.

Photo sourced from http://www.winterwar.com/images/GunsWrecoil/76k23c.jpg

The St Chamond-manfactured76 K/23 (76mm cannon model 1923)

Photo sourced from http://www.winterwar.com/images/GunsWrecoil/76k23c.jpg

The St Chamond-manfactured76 K/23 (76mm cannon model 1923)

In the end however, as will be mentioned in an upcoming Post on Maavoimat Artillery, the results of the evaluation of these guns had been disappointing and as the artillery arm of the Maavoimat was strengthened through the period between 1935 and 1938, a considerable number of the Skoda 75 mm Model 1935 Field Guns and a rather smaller number of the Škoda 149 mm K (149 H33) had been purchased. The Skoda 75 mm Model 1935 gun had been the Maavoimat’s light artillery weapon of choice - it was a mountain gun manufactured by Skoda Works, in Czechoslovakia (a variant was produced in Russia as the 76 mm mountain gun M1938) and Skoda delivered Finland a compatible 76mm version. The gun was light, easy to transport, could be broken down into 3 sections, and further broken down into ten horse loads (summer) or sledge loads (winter). The gun crew was given some protection by an armoured shield. As we will see, the Finnish Army had placed a large initial order with Skoda Works, the Czechoslovakian arms manufacturer, in 1935 with delivery scheduled over 5 years. Initial shipments commenced in mid-1936.

At the same time, the Maavoimat also licensed the design for the Skoda 76mm and Skoda worked with VTT (the Finnish State Gun Factory) to set up a production line. This was an involved process with specialised machinery and training required, resulting in the line being eventually up and running only by late 1937. Over 1938, approximately 100 guns were produced and even with the move to double shifts in late 1938 after the cancellation of the Skoda deliveries, output was raised by only 50% as there were serious bottlenecks in areas such as the supplies of barrel blanks and machined parts. In addition, contracts had been placed within Finland with Ammus Oy for the setting up of munitions production lines for both the Skoda 76mm and for the Bofors/Finnish designed and Tampella-built 105mm Howitzer.

Unfortunately for Finland, the Munich Crisis and the seizure and dismemberment of Czechoslovakia had led to deliveries of the Skoda 76mm being cut short as Germany took over all Czech arms output. Finland protested to Germany over this, but to no avail. Fortunately, payment was being made on delivery to Finland and while there were no financial losses involved, only 60% of the numbers ordered had been delivered when the order was abruptly curtailed. The planned TOE for artillery units being equipped with the Skoda 76mm was incomplete and as a result, in early 1939 the Maavoimat began looking for alternatives. In the end, this boiled down to the French as British manufacturing capacity was going towards equipping their own forces (although in the end, after the Winter War had started, they would sell artillery pieces to Finland) and France had the industrial manufacturing capacity and was willing (with suitable incentives to the appropriate French politicians – something that Finland reluctantly and rather distastefully arranged) to sell. The end result was the placement of two orders.

Schneider-manufactured 76 K/22 (76 mm Cannon Model 1922) – 100 ordered in March 1939, delivered between August and December 1939

In March 1939, an emergency order for 100 of the Schneider 76 K/22 (76 mm Cannon Model 1922) guns had been placed. The gun was not considered perfect but the French government had agreed to the sale and Schneider had agreed to rush the manufacturing through (although in practice they did no such thing). A first batch of 36 was delivered in August 1940 and the remainder of the order was delivered in December 1939, shortly after the outbreak of the Winter War.

Schneider 105 K/13 (105mm Cannon Model 1913 / Canon de 105 mle 1913 Schneider)

One of the Maavoimat’s major weaknesses that had been identified in the 1931 Defense Review was in Heavy Field Guns. This was a serious weakness in that without such guns, counter-battery capability and striking targets far behind enemy lines was impossible, placing the Maavoimat at a serious disadvantage in battle. Before the Winter War Finland had managed to improve the situation by buying a number of the Škoda 149 mm K (149 H33) guns from Czechoslovakia (again, the deliveries of these guns were cut short after the Munich Crisis). It had also proved possible to buy an additional 114 heavy field guns from the Germans (despite the somewhat icy relationship after the Skoda Works orders were cancelled). However, even after these purchases, Finnish long range artillery capabilities remained weak and were a source of serious concern, particularly as pressure and threats from the Soviet Union grew in intensity. The end result was that in conjunction with the March 1939 order for the Schneider 76 K/22 (76 mm Cannon Model 1922), the Maavoimat had contracted with the French government for the purchase of 150 pieces of the Canon de 105 mle 1913 Schneider.

Photo sourced from: http://www.jaegerplatoon.net/105K13_1.jpg

The Schneider 105 K/13 (105mm Cannon Model 1913)

Photo sourced from: http://www.jaegerplatoon.net/105K13_1.jpg

The Schneider 105 K/13 (105mm Cannon Model 1913)

The gun had its origins in the early 1900s when the French company, Schneider et Cie, began a collaboration with the Russian Putilov company. For this collaboration, it had developed a gun using the Russian 107 mm round, which was ordered by the Russian Army to be produced in Russia (though the initial batch of guns was made in France). Schneider then decided to modify the design for the French 105 mm round and offer it to France as well. Initially the French army was not interested in this weapon as they already had plenty of 75 mm field guns and not seeing the use, they ordered only a small number. However, the lighter 75 mm guns had proved of limited use in trench warfare of WWI and so the French army ordered large numbers of the L 13 S, which with its larger 15.74 kg (34.7 lb) shell was more effective against fortified positions. After the end of WWI, France had large numbers of these guns (some 1300 in all), many of which were considered surplus to requirements and so many Schneider 105 mm guns were sold or given away to various other countries, including Belgium, Czechoslovakia and Estonia. The gun was also manufactured under license in Italy, Poland and Yugoslavia.

Photo sourced from: http://www.jaegerplatoon.net/105K13_2.jpg

The Schneider 105 K/13 (105mm Cannon Model 1913) had a sturdy gun carriage

Photo sourced from: http://www.jaegerplatoon.net/105K13_2.jpg

The Schneider 105 K/13 (105mm Cannon Model 1913) had a sturdy gun carriage.

The gun had a box trail, gun shield, wooden wheels with steel hoops (the maavoimat fitted rubber tired wheels on delivery) and a recoil system of hydraulic buffer + pneumatic recuperator independent from each other located under the gun barrel. The Breech System had a screw breech. Ammunition was the cartridge seated type with two propellant charge sizes and ammunition with reduced propellant charge. The guns were horse-towed with a maximum speed of about 10 km/h. Rate-of-fire was about 4 shots per minute. A Cannon Wagon was used in front of the gun when horse-towed and carried 14 shots for the gun. In France they remained in large-scale use even in 1940, when the Germans managed to capture about 700 of them. German military called the gun 10.5 cm Kanone 331 (f) and used them both as field guns and coastal guns.

The Finnish order of March 1939 for 100 of the Scheider 105mm Cannon Model 1913 was met with a single shipment of existing pieces from French Army storage depots. In addition, approximately 250,000 shells were supplied (again, from the large existing French stockpiles) and these were delivered in the Summer of 1939 by ship to Turku. In September 1939, after war with Poland had broken out, Finland placed an emergency order for a further 150 of the guns. After some considerable time, this was approved and a shipment of 12 guns was delivered in February 1940 together with 20,000 shells. In March 1940, an additional 38 guns together with a further shipment of 85,000 shells were shipped together with the Polish Division. The guns would enter service in May 1940. In Maavoimat service, they gained a reputation as an effective and durable artillery piece. They were only declared obsolete in the late 1960’s. The remaining 100 guns of the order would not be delivered.

Photo sourced from: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/c ... inna_2.jpg

A French 105 mm M1913 Schneider gun, displayed in the Hämeenlinna Artillery Museum. The barrel of this particular gun was manufactured in 1918 and the gun carriage in 1916. The rubber tires were added after the gun was brought into Finnish service. The gun had a combat weight of 2,300kgs, a calibre of 105mm x 390R (cartridge seated ammunition) and a maxium range of 12kms. Shells weighed 14.9kg and were HE.

French Aid after the outbreak of the Winter War

The 90 K/77 (90mm Cannon Model 1877) – 136 of these were donated to Finland

Photo sourced from: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/c ... inna_2.jpg

A French 105 mm M1913 Schneider gun, displayed in the Hämeenlinna Artillery Museum. The barrel of this particular gun was manufactured in 1918 and the gun carriage in 1916. The rubber tires were added after the gun was brought into Finnish service. The gun had a combat weight of 2,300kgs, a calibre of 105mm x 390R (cartridge seated ammunition) and a maxium range of 12kms. Shells weighed 14.9kg and were HE.

French Aid after the outbreak of the Winter War

The 90 K/77 (90mm Cannon Model 1877) – 136 of these were donated to Finland

France had lost the War of 1870 - 1871 was against Germany. One of the main reasons for that was that French artillery had not been as up to date as German artillery. This gave an impetus to the French to introduce new artillery weapons for their Army in the late 1870's. However, when in 1914 the French Army still found itself facing a shortage of \modern artillery weapons, the old "Mle 1877" and "Mle 1878" field guns were re-introduced for use even though they were verging on obsolete then. Over the course of WW1, France managed to replace most of these old guns with modern artillery pieces, but as the old "Mle 1877" and "Mle 1878" guns had served well and were still effective, they were carefully stored for possible future use by the Reserve units of the French Army. When WW2 started, the French considered issuing the old guns for use on theMaginot-line, but instead decided to leave them in their warehouses.

Despite the ongoing buildup of the Finnish Armed Forces through the 1930’s, there was still a shortage of Artillery within the Maavoimat when the Winter War started at the end of November 1939. The Maavoimat had built up a considerable strength in Artillery but with the first total mobilization in Finnish history, together with the arrival of thousands of volunteers, there was a serious shortage of artillery and ammunition. As a result of this situation, Finland was willing to buy just about any artillery any country was willing to sell and once more asked France about purchasing artillery. France refused to sell any modern artillery but with the political optics of being seen to assist Finland in mind, the French Prime Minister, Édouard Daladier advised that France was willing to donate large number of older "Mle 1877" and "Mle 1878" artillery guns (which the French no lionger had any use for) and that these guns could be delivered with large amounts of readily available ammunition. Large numbers of these guns were promised, and Finland gratefully accepted – particularly as they were being donated rather than sold.

Assembling and shipping the guns and ammunition took time. Not only did it take time to extract them from the storage depots in France, they needed to be moved to the docks, a suitable ship found and passage arranged. As it was, the first shipment of 24 guns (all the "90 K/77" model) reached frontline units only in mid-March 1940. These first guns were shipped from France to Narvik in Norway. From Narvik they were transported by rail through Norway and Sweden to the Finnish border at Torneå/Tornio. At Tornio they had to be reloaded onto Finnish trains, as the Finnish railways guage was different to the Norwegian and Swedish. Once in Finland, the guns were taken to artillery depots, where they were checked before being issued. These French guns proved to be in much better shape than the old Russian artillery pieces that the Finns already possessed - also originally introduced in 1870's. Not only were the guns in better condition, but the ammunition that the French ammunition supplied with the guns proved more reliable.

Photo sourced from: http://www.jaegerplatoon.net/90K77_1.jpg with permission

A French-supplied 90 K/77 (90mm Cannon Model 1877): Originally designed for direct fire only, they had later had been equipped for indirect fire capability. The gun had a box trail and wooden wheels with steel hoops. Ammunition used was the bagged-type typical of the period (the propellant was packed in bags and was loaded seperately from the projectile and primer). Even with the small caliber, these guns had a very slow rate of fire - only 1 shot per two minutes. France donated 100 of these guns together with 100,000 shells, primers and propellant. They weighed 1200kg, had a maxium range of 9.7kms and fired an HE shell weighing 8.2-8.4kg. A Goniometer, Aiming Ruler and Mirror were the usual instruments used for measuring the azimuth for these older French guns. Correct elevation was measured with a quadrant. Sometimes instruments had to be improvised: If the correct azimuth measuring instruments wasmissing or there was not enough light for using them, a Finnish military compass with its phosphorous needle could be used instead.

Photo sourced from: http://www.jaegerplatoon.net/90K77_1.jpg with permission

A French-supplied 90 K/77 (90mm Cannon Model 1877): Originally designed for direct fire only, they had later had been equipped for indirect fire capability. The gun had a box trail and wooden wheels with steel hoops. Ammunition used was the bagged-type typical of the period (the propellant was packed in bags and was loaded seperately from the projectile and primer). Even with the small caliber, these guns had a very slow rate of fire - only 1 shot per two minutes. France donated 100 of these guns together with 100,000 shells, primers and propellant. They weighed 1200kg, had a maxium range of 9.7kms and fired an HE shell weighing 8.2-8.4kg. A Goniometer, Aiming Ruler and Mirror were the usual instruments used for measuring the azimuth for these older French guns. Correct elevation was measured with a quadrant. Sometimes instruments had to be improvised: If the correct azimuth measuring instruments wasmissing or there was not enough light for using them, a Finnish military compass with its phosphorous needle could be used instead.

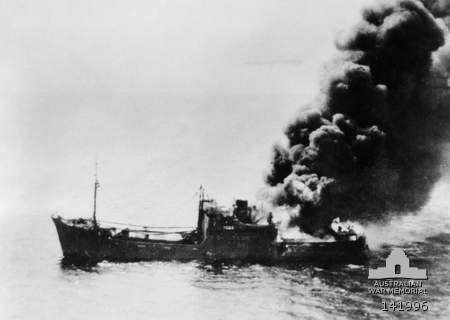

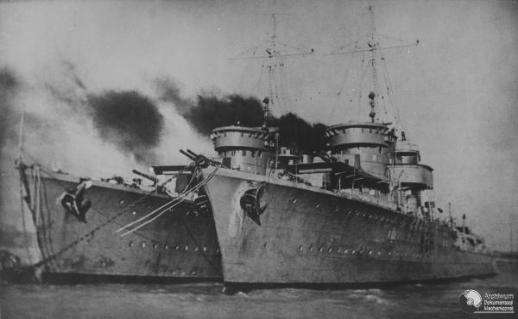

In the end, France shipped 136 of these guns and some 305,000 shells. The remainder of the guns and ammunition were shipped on on the two cargo ships that made up a part of the small convoy to Lyngenfjiord and would only arrive in early April 1940. They were still being unloaded when the Germans attacked Norway and the Maavoimat seized the Finnmark in a pre-emptive action that has been mentioned previously. By the time the remaining guns reached the front, the Maavoimat had established defensive positions that stretched from the outskirts of Leningrad on the Karelian Isthmus, along the Syväri and thence to the Veininmeri (White Sea). The 90 K/77’s were not suitable for mobile warfare, being slow to move. Consequently, the Maavoimat decided to use them on the Syväri Fortifications, and there they served through to the end of the Winter War, by which time their ammunition had started to run low and a considerable number had been lost in action.

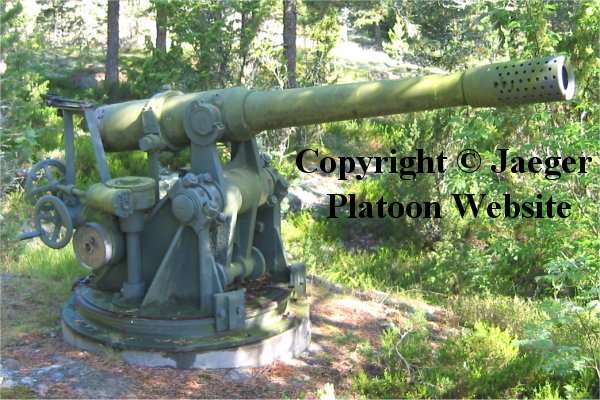

After the Treaty with the USSR had been concluded, a small number of surviving guns were used to augment existing Coastal Defence positions and were fitted to static fortification gun-carriages. The gun-carriage could be bolted either to a concrete structure or to a heavy timber frame. Some 50 carriages were ordered from the Värtsilä factory in late 1940. By late 1943, these had been completed and installed in a number of existing coastal battery positions although they were never used in action and were finally declared obsolete in the 1960’s. The guns not ear-marked for use were placed in storage. After WW2 ended, these guns became popular for monumental use.

Photo sourced from http://www.jaegerplatoon.net/90K77k_1.jpg and used with permission

French-supplied 90 K/77 (90mm Cannon Model 1877) fitted to static fortification gun-carriage and used in Coastal Defence positions

The 120 K/78 (120 mm Cannon Model 1878) – 72 of these were donated to Finland

Photo sourced from http://www.jaegerplatoon.net/90K77k_1.jpg and used with permission

French-supplied 90 K/77 (90mm Cannon Model 1877) fitted to static fortification gun-carriage and used in Coastal Defence positions

The 120 K/78 (120 mm Cannon Model 1878) – 72 of these were donated to Finland

The 120mm Cannon Model 1878 was the medium-calibre French de Bange gun. The Fremch had continued to use these throughout WWI and they also saw some use with the Serbs. The gun was usually used with cingali wheel plates (known as "Centure de Roues" by the French) fastened to the wheels with in order to reduce recoil. The gun used bagged ammunition. The weapon also had a specially designed recoil reduction system, which was installed in end of the box trail. The wheels were usually wooden with steel hoops. The gun had been intended to be towed by 6 - 8 horses, but it was slow to tow (only about 4 km/h) and getting the gun ready to fire once it had arrived in its position took about an hour. In the French use the average rate of fire for this gun was about 1 shot per minute (or 46 - 50 shots per hour).

Photo sourced from: http://www.jaegerplatoon.net/120K78_1.jpg and used with permission

The 120 K/78 (120 mm Cannon Model 1878): France donated 72 of these guns early in the Winter War together with 96,000 shells. They weighed 3750kg, had a maxium range of 12.4kms and fired an HE shell weighing 18.8-20.0kg. The entire shipment arrived in early April together with the bulk of the 90 K/77 guns. They were issued to artillery units and usage was all on the Karelian Isthmus, where the heaviest of the Red Army offensives took place. As usual the gun was turned around to the correct azimuth by prying the end of the gun trail with crowbars. The aiming system was on top of the breech and a mirror used for determining the correct azimuth was on the left side of the gun carriage. In the early 1930's the Poles developed an improved version by installing the barrels of this 120-mm French gun onto the carriages of Russian 152-mm howitzers. The resulted combination was called "120mm wz. 1878/09/31" and "120mm wz 1878/10/31" by the Poles – and was also used by the Finns during WW2, becoming known as the "120 K/78-31" in Finland.

Photo sourced from: http://www.jaegerplatoon.net/120K78_1.jpg and used with permission

The 120 K/78 (120 mm Cannon Model 1878): France donated 72 of these guns early in the Winter War together with 96,000 shells. They weighed 3750kg, had a maxium range of 12.4kms and fired an HE shell weighing 18.8-20.0kg. The entire shipment arrived in early April together with the bulk of the 90 K/77 guns. They were issued to artillery units and usage was all on the Karelian Isthmus, where the heaviest of the Red Army offensives took place. As usual the gun was turned around to the correct azimuth by prying the end of the gun trail with crowbars. The aiming system was on top of the breech and a mirror used for determining the correct azimuth was on the left side of the gun carriage. In the early 1930's the Poles developed an improved version by installing the barrels of this 120-mm French gun onto the carriages of Russian 152-mm howitzers. The resulted combination was called "120mm wz. 1878/09/31" and "120mm wz 1878/10/31" by the Poles – and was also used by the Finns during WW2, becoming known as the "120 K/78-31" in Finland.

The Maavoimat had shortage of heavy long-range cannon and the 120 K/78’s were often used in roles which in other Armies were usually carried out using modern heavy cannon or howitzers. Finnish soldiers found the guns to be surprisingly accurate and with quite effective HE projectiles. The Maavoimat usually transported the guns with trucks. Towing the whole gun proved somewhat problematic, so the barrel was usually removed and transported in the truck while the rest of the gun was towed. The lifting ring on top of the gun barrel was useful for removing the barrel and reinstalling it, but a small crane was needed for the job – meaning the guns were not at all mobile. With hard training and experience Finnish gun crews also managed to raise the rate-of-fire to 2 shots per minute.

The guns saw heavy use on the Isthmus, in particular during the Red Army’s summer offensive – when 16 guns had to be left behind in June 1940 when Finnish troops temporarily retreating in the face of overwhelming Red Army numbers had to withdraw rather faster than anticipated. And in the final Soviet attacks of late August 1940, a Soviet unit managed to surprise the 78th Fortification Artillery Battery in the Karelian Isthmus sector, capturing its guns and taking two of them back to their own side of frontline. These guns fired their last shots of the Winter War on 24th of September 194, after which they were placed in storage.

The 155 K/77 (155 mm Cannon Model 1877) – 48 of these were donated to Finland

France had introduced two versions of the 155-mm de Bange gun in the late 1870's. From those two this was the long-barrelled version. Like other French de Bange guns they saw use during WW1 and the French kept them stored after that. They were the heaviest and largest-calibre cannons of the French de Bange artillery system. The basic structure of the gun was same as used in other smaller-calibre models: The gun had a de Bange screw breech and box trail. As typical the ammunition used was bagged type. But the gun also had steel wheels instead of the usual wooden ones.

During the Winter War France donated 48 guns of these guns and 48,000 shells to Finland. The Finnish military found the gun to have effective projectiles, good accuracy and quite a good range, but the bulk and weight of the gun made both using and transporting it difficult. Because of the shortage of heavy long-range guns the 155 K/77 guns were often used in roles such as counter-artillery, for which better equipped Armies used modern heavy guns and gun-howitzers. The transport method used was the same, as that used with the 120 K/78 guns. The barrel of the gun was usually placed on the truck body and the same truck towed the gun carriage.

The guns first saw use in battle on the Karelian Isthmus following which they were given to Syväri (Svir) Fortification Battalions, which used them until the Soviet offensive started on the Syväri/Svir in June/July 1940. The old guns were not a priority and there was little transport capacity available for transporting the old and heavy 155 K/77 guns to safety. So as they retreated the Finnish troops demolished 24 of the guns and left them behind. Very likely this was the last time in the whole world for cannons which had no recoil system to be used in battle.

Photo sourced from: http://www.jaegerplatoon.net/155K77_1.jpg

The 155 K/77. Notice the wheels, which have a rather unique look

The 155 H/15 (155 mm Howitzer model 1915, St Chamond) – 24 purchased from France

Photo sourced from: http://www.jaegerplatoon.net/155K77_1.jpg

The 155 K/77. Notice the wheels, which have a rather unique look

The 155 H/15 (155 mm Howitzer model 1915, St Chamond) – 24 purchased from France

The French Saint-Chamond factory had designed this howitzer for the export market, but when WWI started the French Army instead becmme the main customer for this howitzer. Depending on the source, some 360 - 390 of these howitzers were manufactured for the French Army during WW1. However the Canon de 155C, mle 1917 Schneider Howitzer manufactured by the competing Schneider factory proved better during the war, so the manufacture of this Saint-Chamond howitzer was stopped. However, thse Howitzers already manufactured remained in use with the French military until 1940, when the Germans invaded France. The German military captured almost 200 of these howitzers intact (and reissued large number of them for their own units, mostly to coastal defences located in France).

Certain characteristics of the howitzer were quite advanced for its time: It had semi-automatic breech mechanism with a vertical sliding breech block, which ejected the used cartridge case after firing a shot. The Elevation system of the howitzer didn't tilt the barrel (as was usual), but lifted the forward part of gun carriage up from the axle. Instead of the usual dial-sight, the howitzer had collimator and angle-director as sights. It also had a conventional box trail (with a hole in middle for achieving more elevation), wood wheels with steel hoops and a recoil mechanism with a spring / hydraulic buffer / recuperator system located below the barrel. The gun shield was unusually low and gave only limited protection to the crew. Rate of fire was around 2 - 3 shots/minute.

Photo sourced from: http://www.jaegerplatoon.net/155H15_1.jpg

The 155 H/15 weighed 3,040kg, had a range of 6.9-9.0 kms, a caliber of 155mm x 250R (cartridge seated ammunition) and a shell weighed 43-43.5kgs.

Photo sourced from: http://www.jaegerplatoon.net/155H15_1.jpg

The 155 H/15 weighed 3,040kg, had a range of 6.9-9.0 kms, a caliber of 155mm x 250R (cartridge seated ammunition) and a shell weighed 43-43.5kgs.

Finland bought 24 of these howitzers from France during the Winter War. Depending on the source either 20,000 or 32,000 shots were bought with these howitzers. The howitzers arrived in early March 1940 and were issued to Heavy Artillery Battalions 27 and 29, who used the howitzers over the remaining 6 months of the Winter War to considerable effect. None of the howitzers were lost in battle. As mentioned the ammunition used was the cartridge seated type with six propellant charge sizes. The only kind of ammunition Finnish manuals list for these howitzers was the high-explosive (HE) type.

155 H/17 Tuhkaluukku (155 mm Howitzer Model 1917 "ash box door" / (Canon de 155 C, mle 1917 Schneider)

This howitzer was related to another Schneider design, the Russian 6 dm polevaja gaubitsa sistemy Schneidera (152 H/10) heavy howitzer. The howitzer first entered service with the French Army in 1917 and soon proved an excellent artillery weapon. A little more then 2,000 were still in use with the French Army in 1939 – 1940, although a considerable number of these were either warehourse or inventoried as parts. The howitzer was also sold very successful abroad. It was known as the "155 mm Howitzer M1917" in the United States, where the howitzer and its improved version, the "155 mm Howitzer M1917A1" were manufactured under license. In Poland the howitzer was known as the "155 mm Haubica wz. 1917" and in Italy it was known as the "Obice de 155/14 PB". Some where also delivered to Russia, where the Soviets later modified them to a caliber of 152.4-mm (this version is commonly known as the "152-17S"). Other user countries included: Belgium, Brazil, Greece, Romania and Yugoslavia. Being so numerous and widely spread, large number of these howitzers fell into German hands when they occupied these countries. The Germans called the most numerous version (previously owned by France) the "15,5 sFH 414" and the Soviet version the "15,2 cm sFH 449 (r)". The captured howitzers saw use with both German Field Artillery and coastal defence.

The howitzers basic design was quite conventional for its time. It had a box trail (with the usual hole in the middle of it), a screw breech, a recoil system with a hydraulic buffer and pneumatic recuperator and a curved gun shield. The wheels were wood with steel hoops. The howitzers were equipped so as to be suitable for both motorised towing and being towed with horses. A Limber was used while towing it with horses - this could also be used in slow motorised towing. In Maavoimat use, for faster motorised towing the howitzer had a Finnish-made special limber with pneumatic tires and a separate towing arm. During wintertime the maavoimat could also use its own special sledge in front of the howitzer to make towing of the howitzer on snow covered roads easier. The maximum speed for towing with horses was 8 km/h and maximum speed in motorised towing but without the special Finnish-made limber for motorised towing was only 10 km/h. The Finnish-made special limber allowed motorised towing with speed of up to 20 km/h. The weight of the howitzer when ready for transport was about 3,800 kg and the limber used with horses weight an additional 415-kg. The rate of fire for this howitzer was about 3 shots/minute.

Photo sourced from: http://www.jaegerplatoon.net/155H17_1.jpg

The 155 H/17 heavy howitzer. The 155 H/17 weighed 3,300kg in action, had a range of 10.3 – 11.0 kms, a caliber of 155mm, used cartridge seated ammunition and a shell weighed 43-43.6kgs. The Finnish manuals list all ammunition for this howitzer as being of the high explosive (HE) type with 7 propellant charge sizes (both full-charge and reduced-charge versions of propellant charges existed).

Photo sourced from: http://www.jaegerplatoon.net/155H17_1.jpg

The 155 H/17 heavy howitzer. The 155 H/17 weighed 3,300kg in action, had a range of 10.3 – 11.0 kms, a caliber of 155mm, used cartridge seated ammunition and a shell weighed 43-43.6kgs. The Finnish manuals list all ammunition for this howitzer as being of the high explosive (HE) type with 7 propellant charge sizes (both full-charge and reduced-charge versions of propellant charges existed).

Finland bought 166 of these howitzers from France, with the order placed in December 1939. The first batch, which arrived in February of 1940, contained 15 howitzers. The remaining 151 howitzers were delivered in March 1940 together with a large quantity of shells (numbers not available, but despite heavy use there were large stocks of shells in existence after the Winter War ended so the shipment must have been of considerable size). Many of them arrived in very poor shape and it is entirely possible that the French had put them together from spare parts that were not part of the official inventory. However, the Maavoimat rapidly repaired them for operational use and they would go on to be heavily used by the Finnish Field Artillery over the remainder of the Winter War.

They were issued to five Heavy Artillery Battalions (1st, 20th, 25th, 26th and 29th) and saw use with no less then eight Field Artillery Regiments (1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th, 8th, 11th and 14th). Finnish soldiers liked the howitzer, even if the seals of its recoil system caused problems in winter and some gun carriages broke down. According to original documents at least 14 howitzers were lost in battle over the summer of 1940. Five of them belonging to Heavy Artillery Battalion 20 were lost on the 10th of June. The other lost howitzers were seven howitzers belonging to Field Artillery Regiment 3 and two howitzers belonging to Field Artillery Regiment 11, which were all lost in fighting on the Syvari front. After WW2 the howitzers remained warehoused for possible wartime use and in live-fire training use. The original wheels were replaced with new twin wheels with pneumatic tires in the 1960's. As the amount of already manufactured ammunition was quite large the howitzers remained in live-fire training use until the 1980's.

75 K/97 "Marianne" (75 mm Cannon Model 1897 / Materiel de 75, Modele 1897) – 48 purchased from France in early 1940

This French gun was the first field gun equipped with a modern recoil system and thew first field gun designed around the quick-fire concept. At the time France and Germany were having an arms race of sort. The French received (false) intelligence data claiming that the Germans had developed a field gun with a successful recoil system – and decided that they also had to get their own version of this, and fast. The vital buffer/recuperator system using oil and compressed air was based on an earlier design by Belgian Colonel Locard. Otherwise the gun design can be credited to French officers Colonel Albert Deport and Captain Sainte-Claire Deville. In recoil the gun barrel ran on top of 6 pairs of rollers with bronze sleeves being used as the sliding surface. The gun had a shield, the top part of which could be folded. The gun also had the typical wooden wheels with steel hoops. The wheel anchors were used to lock the wheels during firing and removed the last bit of recoil - because of this the gun, wich used a Nordenfelt screw breech, could achieve rate-of-fire as high as 20-shots/minute.

The gun proved to be excellent direct fire weapon and became the pride of the French field artillery before World War 1. However, the gun was not exactly easy to manufacture as some parts demanded a very exact fit. Despite this the Schneider factory manufactured an estimated 16,000 - 17,000 of them. During WW1 the admiration and trust that the French had placed in their excellent Materiel de 75, Modele 1897 proved to have its downside - the French Army had neglected developing heavier artillery, which proved to be vital against an entrenched enemy. As the French Army also lost their 75-mm guns in large numbers during the early part of WW1, they had to reintroduce older guns without recoil systems back into combat. During its versatile career the gun was adapted as a self-propelled artillery piece, for aircraft (B-25 bomber) and as an antiaircraft-gun. After WW1 the largest modification the French introduced for these guns was replacing the original wheels with ones that had rubber tires and but even this was not done for all guns. The French did introduce the modernized split-trail version, the Canon de 75 mle 97/33 in 1930's, but only in relatively small numbers.

Another large manufacturer of these guns was the United States, which acquired some 4,300 of them during World War 1 and kept using their own versions, the 1897A2 and 1897A4 during World War 2, (although the gun didn’t serve the US military as an actual field gun for long in that war). Other users included Estonia, Great Britain, Greece, Ireland, Lithuania, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal and Romania. During WW2 the Germans captured French 75mm model 1897’s in many countries, with the largest numbers being about 1,000 in Poland and an estimated 3,000 - 4,000 in France. The Germans old some of the captured guns to Romania. After facing KV- and T-34 tanks on the Eastern Front the Germans found they had an immediate need for large-calibre anti-tank-guns. In 1942 they manufactured about 600 7.5 cm Pak 97/38 (75 PstK/97-38) anti-tank-guns by combining a re-chambered barrel from the French 75-mm model 1897 with the gun carriage from the 5.0 cm Pak 38 (50 PstK/38). Names used by some users:

• Poland: 75 mm armata polowa wz. 97/17

• Great Britain: Ord. QF 75 Mk 1

• USA: 75 Gun M 1897

• Germany: 7,5 FK 231 (f) and 7,5 FK 97 (f)

The gun remained in French use until the 1960's and in use even longer in some third world countries. It has been estimated that this gun might be the most numerous field gun model manufactured anywhere in the world.

Photo sourced from: http://www.jaegerplatoon.net/75K97_1.jpg

The Maavoimat’s 75 K/97 "Marianne" (75 mm Cannon Model 1897 / Materiel de 75, Modele 1897): With a caliber of 75mm x 350R (fixed ammunition), the weight in action was 1,140kg, maximum range was 7.9 km but with reduced charge ammunition the range was around 6.3 - 6.4 km. Muzzle velocity was 550m/sec and ammunition weight was 6.3-7.8kg (HE) and 6.4-6.1 kg (AP). The gun was designed to be horse-towed (but the Finnish troops sometimes transported it on the back of a truck) with a maximum speed of about 8 km/h. A Limber was used with the gun when horse-towed, this weighed 830 kg loaded and carried 27 shots for the gun.

Photo sourced from: http://www.jaegerplatoon.net/75K97_1.jpg

The Maavoimat’s 75 K/97 "Marianne" (75 mm Cannon Model 1897 / Materiel de 75, Modele 1897): With a caliber of 75mm x 350R (fixed ammunition), the weight in action was 1,140kg, maximum range was 7.9 km but with reduced charge ammunition the range was around 6.3 - 6.4 km. Muzzle velocity was 550m/sec and ammunition weight was 6.3-7.8kg (HE) and 6.4-6.1 kg (AP). The gun was designed to be horse-towed (but the Finnish troops sometimes transported it on the back of a truck) with a maximum speed of about 8 km/h. A Limber was used with the gun when horse-towed, this weighed 830 kg loaded and carried 27 shots for the gun.

Following the Munich Crisis, Finland drastically increased defence spending in all areas. In assessing the threat posed by the Red Army, it was evident that the large amroured formation and the many thousands of tanks the Red Army could mobilize would pose a considerable threat. While Maavoimat had ordered 37mm anti-tank guns from Bofors, and a Tampella version was also being manufactured under license, there was still a serious shortage of these particular weapons throughout the Maavoimat. In addition, the Maavoimat had started having doubts about the effectiveness of the Bofors 37mm during Spanish Civil War, hence the conversion program that had been initiated to convert the Bofors 76mm into an antitank gun in early 1938. Unfortunately, there seemed to be nothing else as effective available on the arms market that Finland could buy and so the Maavoimat began looking at alternatives. Germany declined to sell (although there were some exceptions) but France, a leading manufacturer of artillery and guns of all sorts, was amenable.

A suggestion was made (the origins of the suggestion are unknown but may have been from a Maavoimat artillery officer familiar with the then highly secret project to mount a Bofors 76mm in a turretless version of the Czech LT-38 that the Maavoimat had purchased a license to manufacture) that a number of the old Materiel de 75, Modele 1897’s in stock could be taken and modified for use by the Finns – an attractive proposition for the French as it meant they would sell weapons that had no real value except as scrap and in addition, could make money from the Finns by refurbishing them and fitting them to new carriages. Many of the guns in stock had barrels that were in a terribly worn down condition, causing dangerously large dispersion when used to shoot indirect fire from long range. However, they were available in large quantities and they were cheap. In the original configuration these guns were ill suited for fighting tanks because of their relatively low muzzle velocity, limited traverse (only 6°), and lack of a suitable suspension (which resulted in a transport speed of 10–12 km/h).

Scheider proposed to solve the traverse and mobility problems by mounting the 75 mm barrel on a modern split trail carriage. To soften the recoil, the barrel would be fitted with a large muzzle brake. The gun was primarily intended to use HEAT shells as the armor penetration of this type of ammunition doesn't depend on velocity (the 75 had a fairly low muzzle velocity of 550m/sec meaning it would have insufficient performance with an AP shell). And even with HEAT, the gun would have a low effective range – only about 500m. Finland had agreed to the French/Schneider proposal in February 1939, signing an order for 250 guns. The Schneider factory began refurbishing and rebuilding the guns and building gun carriages based on a design provided by the Maavoimat (who had in turn acquired this somewhat surreptitiously from the Germans through personal connections).

Work progressed slowly, with the first 48 guns and 50,000 HEAT shells delivered in July 1939. Thereafter, August saw the delivery of 52 guns and a further 50,000 shells, whilst in September another 40 guns were delivered. The outbreak of war between Germany and France put a hiatus to deliveries for some two months, but on the outbreak of the Winter War, the French Government saw fit to permit delivery to go ahead and the remaining 110 guns together with 150,000 HEAT shells were delivered in late December 1939. When the French delivered the guns to Finland in late December, they arrived disassembled but with two teams of advisors to help the Finns assemble and train with them. The first team, the "artillery equipment team" lead by Captain Garnier was quite small (2 officers + 3 NCO) and had the task of assisting the Finns with assembling the guns and preparing them for use. The second team, the "artillery training team" commanded by Lt.Col Dion was much larger (25 officers + 27 NCO) and was assigned the mission of training the Finnish troops in the use of the French guns. Both of these teams returned to France in May - June of 1940, by which time all 250 guns were already in service.

Photo sourced fromL http://www.jaegerplatoon.net/75PstK9738_1.jpg

The Schneider-designed 75 PstK/97-38 "Mulatti" (75 mm antitank gun M/97-38 "Mulato"), derived from the 75 K/97 "Marianne" (75 mm Cannon Model 1897 / Materiel de 75, Modele 1897) and modified for the Maavoimat, this was an effective ant-tank gun during the Winter War. Together with light weight, good mobility and sufficient anti-armor performance with the HEAT shell (enough to penetrate a T-26 in most situations; the side armor of a KV could also be pierced), the gun was a decent anti-tank weapon. Some 140 were in service with the Maavoimat on the outbreak of the Winter War. A further 110 entered service through Jjanuary 1940.

Photo sourced fromL http://www.jaegerplatoon.net/75PstK9738_1.jpg

The Schneider-designed 75 PstK/97-38 "Mulatti" (75 mm antitank gun M/97-38 "Mulato"), derived from the 75 K/97 "Marianne" (75 mm Cannon Model 1897 / Materiel de 75, Modele 1897) and modified for the Maavoimat, this was an effective ant-tank gun during the Winter War. Together with light weight, good mobility and sufficient anti-armor performance with the HEAT shell (enough to penetrate a T-26 in most situations; the side armor of a KV could also be pierced), the gun was a decent anti-tank weapon. Some 140 were in service with the Maavoimat on the outbreak of the Winter War. A further 110 entered service through Jjanuary 1940.

The Maavoimat had three kinds of anti-tank-capable ammunition for these guns on the outbreak of the Winter War:

• 75 pspkrv 59/66-ps (French M/1910 APHE projectile with picric filling).

• 75 psa - Vj4 (AP-T projectile with 4 second tracer).

• 75 hkr 42-18/24-38 (Finnish 38 Hl/B HEAT-projectile).

The 75 pstpkrv 59/66-ps shell weighed 6.4 kg and had a muzzle velocity of 570 m/sec. The additional page concerning this ammunition was added to Finnish military manuals on the 1st of September 1939 (but was likely acquired a month or two earlier). This French pre-World War 1 APHE-shell achieved about 60-75mm armour penetration when fired from close range. The AP-shell – the 75 psa - Vj4 was more a modern AP-tracer design. It had a projectile weighing a bit under 6.1 kg and a muzzle velocity of 590 metres/second. A page containing information about this ammunition was added to Finnish military manuals on the 20th of November 11939, but as usual the actual ammunition had probably been introduced month or two before that. However firing of the "75 psa - Vj4" round was recommended in extreme emergency only – the recoil generated by the AP-rounds was fearsome and the gun carriage was not strong enough to endure a lot of shooting with this ammunition.

The recommended antitank ammunion was the Finnish designed and Ammus Oy manufactured HEAT-shells. This ammunition had warheads capable achieving about 60-75mm penetration from 60-degree point of impact when used at close range (500m or less). The gun was introduced into service in November 1939 and worked well in Finnish hands. The short shooting distances typically offered by Finnish terrain made them relatively effective even against the heavily armoured KV tanks. Against the lighter Soviet tanks that were used in large numbers during the Winter War, they were lethal.

Subsequent to the outbreak of the Winter War, Finland attempted to purchase more of the “modified” 75’s. The French government declined but offered to sell Finland 48 unmodified guns together with 50,000 shells. The Finns accepted, with 12 arriving in March 1940 and the remainder in April. The guns were in the same poor condition as the earlier ones had been prior to refurbishing. None of these guns were used during the Winter War and in 1941 they were scrapped.