While there were many more Volunteers who fought with the Atholl Highlanders in Finland, and many of these would men would go on to make a name for themselves in one way or another in WW2, we will restrict ourselves at this stage to covering one final Volunteer - John Malcolm Thorpe Fleming "Jack" Churchill, DSO & Bar, MC & Bar (16 September 1906 – 8 March 1996), nicknamed "Mad Jack" for reasons which will become apparent. Romantic and sensitive, Jack Churchill was an avid reader of history and poetry, knowledgeable about castles and trees, and compassionate to animals, even to insects. He was also a colorful and adventurous British military officer who volunteered to fight in Finland, stormed beaches and led attacks on enemy positions whist playing the bagpipes, who used a Scottish Claymore in battle and who once took 42 Germans prisoner at swordpoint. He may also well be the last soldier in a European army to kill an enemy with a longbow.

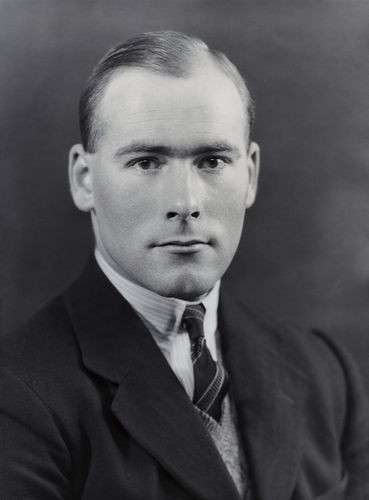

"Jack" Churchill was a professional soldier, the son of an old Oxfordshire family. His father, Alex Churchill, was on leave from the Far East, where he was Director of Public Works in Hong Kong and later in Ceylon when “Jack” was born on Sept 16 1906 in Surrey. After education at the Dragon School, Oxford, King William's College, Isle of Man, and Sandhurst, Churchill graduated from the Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst in 1926 and was commissioned into the Manchesters Regiment and gazetted to the 2nd Battalion, which he joined in Rangoon. The Regiment had battle honors dating back to the 18th century, having originally been raised as the 63rd and 96th Regiments of Foot and had shed blood fighting for Britain across the world. Forty-two battalions of the Manchesters served in World War I alone. Churchill’s younger brother, Tom, also became a Manchesters officer, and in time would rise to major general, retiring in 1962. Another younger brother, Buster, opted for the Royal Navy’s Fleet Air Arm and died off Malta in WW2.

That Jack Churchill was somewhat of a “free spirit” was obvious from the beginning of his army service, even in an army rich in such men. As just one example, while serving in Burma before the outbreak of WW2, he attended a course in signals at Poona in India. It might appear odd to some that Churchill rode his Zenith motorcycle most of the way from Rangoon to Poona, but it did not seem at all remarkable, at least to Churchill, to return the 1,500 miles from Poona to Calcutta—whence he was to take a ship for Rangoon—riding his motorcycle. Along the way he lost a contest with a large and hostile water buffalo but returned to his unit in time to serve in the Burma Rebellion of 1930-32. Unusual hazards and difficulties never meant much to Churchill. On the same motorcycle he had traveled the 500 miles through Burma from Maymyo (a Hill Station in Shan State in the north of Burma) to Rangoon, a trip substantially complicated by an absence of roads. He therefore followed the railroad line, crossing the dozens of watercourses by pushing the bike along a rail while he walked on the crossties. Everything in life was a challenge to him. Included in the challenges to which he rose was mastering the bagpipe, a peculiar attachment for an Englishman. His love affair with the pipes seems to have originated in Maymyo, where he studied under the pipe major of the Cameron Highlanders.

Back in England in 1932, Churchill kept on studying the pipes, but the peacetime army had begun to pale for him. Churchill was one of those unusual men designed to lead others in combat, and such men are often restless in time of peace. And perhaps, as his biographer commented, “certain eccentricities—brought on no doubt through frustration—such as piping the orderly officer to the Guard Room at three o’clock of a morning, and studying the wrong pre-set campaign in preparation for his promotion exam, precluded any chance of promotion for the time being and made the break, after a chat with his commanding officer, inevitable.” When Churchill managed to get himself reprimanded for using a hot water bottle, a distinctly non-military piece of equipment, he circumvented this nicety of military protocol by substituting a piece of rubber tubing, which he filled from the nearest hot water tap. And then there was the day on which he appeared on parade carrying an umbrella, a mortal sin in any army. When asked by the battalion adjutant what he meant by such outlandish behavior, Churchill replied “because it’s raining, sir,” an answer not calculated to endear him to the frozen soul of any battalion adjutant.

But when the regiment returned to Britain in 1936, he became bored with military life at the depot at Ashton-under-Lyne and for whatever reason, after 10 years of service Churchill resigned his commission and turned himself to commercial ventures. A job on the editorial staff of a Nairobi paper did not please him, and so he turned to other tasks. Among other things, he worked as a model in magazine ads and as a movie extra. He appeared in The Drum, a movie of fighting on the Northwest Frontier in which he played the bagpipes. And because he had rowed on the River Isis, he won a cameo in “A Yank At Oxford”, in which he pulled the bow oar in the Oxford shell, with movie star Robert Taylor at stroke. Meanwhile, he continued his piping and in the summer of 1938 placed second in the officers’ class of the piping championships at Aldershot. It was an extraordinary feat, since he was the only Englishman among the seventy or so competitors. During these years out of harness, Churchill practiced another skill as well—archery. He had first tried it only after returning to Britain from Burma. His expertise with the bow got him work in the movies “Sabu” and “The Thief of Baghdad”. And with typical Churchillian determination, he became so good with the bow that he shot for Britain at the world championships in Oslo in 1939. By then, however, the long ugly shadows of war were stretching across Europe.

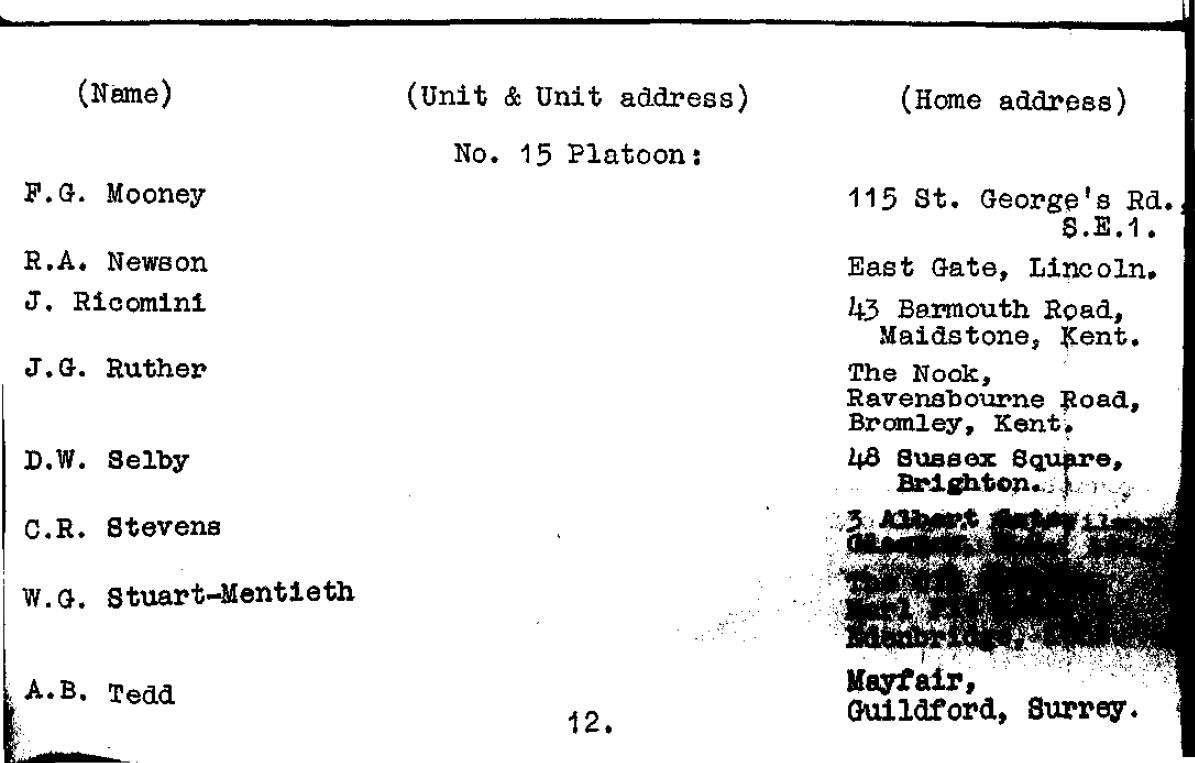

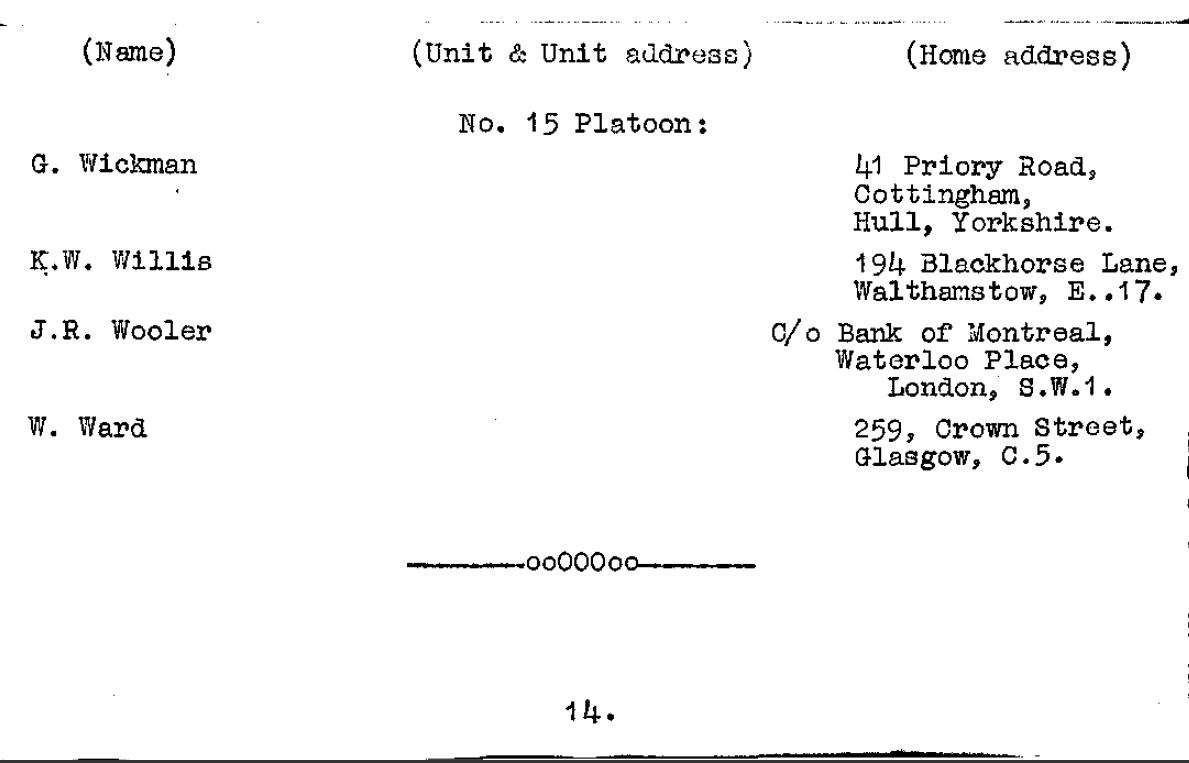

As the German Army smashed into Poland, Churchill returned to the British Army and a commission with the Manchester Regiment. “I was,” he said later, “back in my red coat; the country having got into a jam in my absence.” He was obviously happy to be soldiering again. After the enlistment of volunteers for Finland was announced, he volunteered for the Atholl Highlanders and service in Finland, unsure of what it was all about but interested because it sounded dangerous and “Wingate was crazy, but he was crazy like a fox, which made him an interesting chap to fight under.” Like appeals to like and Wingate accepted Churchill immediately, giving him a brevet promotion to Major and placing him in command of “B” Company.

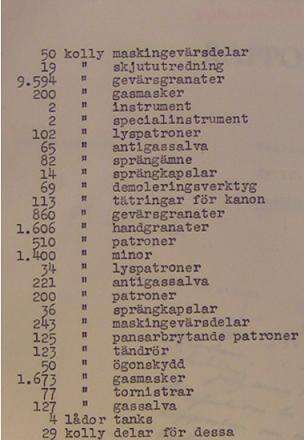

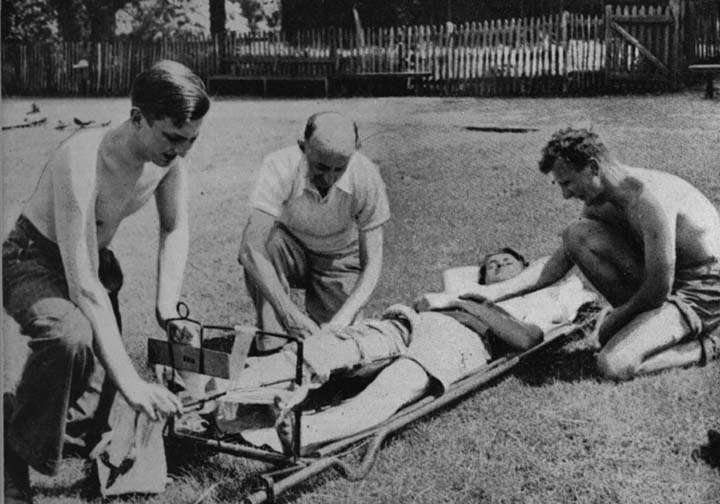

Before embarking, Churchill had Purle of London (one of the finest traditional bow and arrow makers of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries) make him an 85-pound bow of Spanish yew and a quantity of broadhead aluminum hunting arrows. The arrows were expensive, and the money came out of Churchill’s pocket, as it had been several hundred years since the War Office had taken responsibility for archery supplies. The weapon was silent, accurate to 200 yards and lethal in Churchill’s hands. As befitted his love of things Scottish he also acquired a Scottish broadsword, a traditional Claymore (technically a cCaybeg, the true claymore being an enormous two-handed sword).which he would carry with him into battle in Finland and for the remainder of WW2. When Wingate questioned him about the sword, he immediately replied "any officer who goes into action without his sword is improperly armed." Wingate, who was somewhat of an aficionado of the use of cold steel himself, merely laughed. As CO of “B Company, Churchill began rigorously training his men from the moment he took command. On arrival in Finland, he took to the intensive and fast-paced Maavoimat training program like a duck to water, leading his men as they were trained in survival, land navigation, close quarter combat, silent killing, signaling, demolitions, tactical assaults and retreats and shooting, where they learned to use every type of weapon the Maavoimat had in use as well as some of those that they would be likely to encounter in Red Army hands.

OTL Note (Churchill actually volunteered and was accepted for the 5th Battalion, Scots Guards but I’ve moved him to Wingate’s battalion).

On first being posted to the rear lines on the Karelian Isthmus, Churchill volunteered to lead Platoons of the Atholl Highlanders on short stints at the front where the objective was to allow the men to gain combat experience against the Red Army on a “quiet” sector. Perhaps a little frustrated, “Captain Churchill decided on a symbolic gesture that he thought would not only give him great satisfaction but might also create a certain alarm, despondency, and bewilderment in the enemy lines. In his biographers words, “On April 15, while on patrol in no-man’s land, he stealthily made his way to about 50 to 80 yards from the Russian positions and fired three arrows in quick succession. Churchill was quoted as saying “There was a sudden commotion in the enemy’s position, and from the shouting and the confusion it sounded very much as if perhaps one of my broadheads had found a better mark than an inoffensive stag or bushbuck. Anyway, it is pleasant to think so.” The words of the Red Army commander on learning that one of his men had been spitted by a broad-head arrow have not been recorded but may be guessed at.

Churchill was an aggressive leader and trainer, especially fond of raids and counterattacks, leading small groups of picked soldiers against the advancing Red Army and a firm believer in the Maavoimat’s axiom of extracting the maximum cost from the enemy as they attacked, whilst keeping the losses of one’s own men to a minimum. Three days after his first use of the longbow in action, he would lead another Section from one of his Company’s Platoons in an ambush of a Red Army patrol. He presented a strange, almost medieval figure at the head of his men, carrying not only his war bow and arrows, but his sword as well. After ensuring his men were in position to ambush the route the Red Army patrols were using, Churchill gave the signal to attack by silently cutting down the enemy Sergeant with a broadhead arrow, following which the ambush team took out the rest of the enemy patrol. The war-diary of the Maavoimat Regimental Combat Group, to which Churchill’s Company was temporarily attached whilst gaining experience, commented on this extraordinary figure. “One of the most strange sights of the war to date was the sight of Major Churchill of the British Volunteer Battalion passing through the lines with his men and carrying a bow and arrows and a sword. His spitting of Red Army soldiers with his bow and arrows … were a great source of amusement to the men.”

When Wingate volunteered the Atholl Highlanders to augment the Maavoimat ParaJaeger Division on the airborne landings that sowed confusion and chaos in the Red Army rear during the Spring Offensive on the Karelian Isthmus, Churchill leapt at the new challenge. The training period was short, and Churchill reveled in it. He was at home in the Finnish forests and swamps, in the snow and rain and the mud. He lived and breathed training, leading, driving, setting the example, praising excellence, and damning sloth and carelessness. His ad hoc lectures to his soldiers were couched in the plain language his men understood and liked, for instance: “There’s nothing worse than sitting on your bum doing nothing just because the enemy happens to leave you alone for a moment while he has a go at the unit on your flank. Pitch in and support your neighbor any way you can.…” There was also a bit of a downside to Jack Churchill. On those happy occasions when the Company was not in the field doing night training, he was sometimes given to awakening everybody in the Camp as he shattered the night with pipe music. No piper could possibly understand why some of the world would rather sleep than listen to martial piping however expert, and he was no exception. His comrades could only grit their teeth and hope that he would soon tire or think of something rather quieter to do. The training period ended in late April 1940, as the Maavoimat’s brilliantly successful assault down the length of the Karelian Isthmus began.

Churchill commanded “B” company in the attack, and Wingate had put “B” Company in the vanguard of the drop, believing that both Churchill and his Platoon Officers, Lt. Tatham-Warter, 2nd Lt David Vere Stead and 2nd Lt Patrick Dalzel-Job were all “thrusters”. Tasked with seizing two key road junctions and a critically important bridge, the Atholl Highlanders were to seize these at dawn on the first day of the offensive. “B” company would advance straight from the glider landing zone to the bridge while the rest of the battalion took the two road junctions. The initial landings were largely unopposed and the various Companies formed up quickly. Tatham-Warter set up the Battalion rendevous using smoke and lamps, before the order to move off came just after 6am. B Company was in action almost at once; ambushing a small Red Army recce group near the drop zone before moving off through the woods toward the river road, with each platoon taking turns to lead. Tatham-Warter led the vanguard one mile from the dropzone to the bridge at a cost of only one killed and a small number of men wounded whilst having killed something like 150 Russians.

Sourced from: http://www.davidrowlands.co.uk/images/f ... e/1cha.jpg

“B” Company were the only Company of the Atholl Highlanders to wear Kilts into action on the Karelian Isthmus in April 1940. Being unable to acquire genuine Atholl Highlanders kilts before their departure for Finland, Churchill had been given kilts by his old friends in the Cameron Highlanders. His men wore the service dress jacket, the kilt and khaki hose and puttees. No kilt aprons or sporrans were worn. The scene of the action in the painting is the fighting on the Isthmus near 1940. At the left can be seen a gun of the attached anti-tank section. In battle order, the small haversack was worn on the back. Above it was the anti-gas cape, held by two thin white tapes. The respirator was worn on the chest.

In the assault that took the Bridge, Churchill led the charge, his pipes screaming “The March of the Cameron Men.” Churchill and his men killed the Red Army soldiers guarding the bridge and, whilst still fighting off a heavy Red Army counter-attack, Churchill’s signal to Battalion Headquarters was terse: “Bridge captured. Casualties slight. Red Army counter-attacks in progress and being driven off. Churchill.”

The March of the Cameron Men

Withdrawn two days later as the attacking 21st Pansaaridivisoona reached their positions, the Atholl Highlanders would re-equip and regroup over a two day period, following which they would make a further drop on the Isthmus, this time tasked with attacking and eliminating a Red Army Divisional Headquarters. Dropping into the midst of the Divisional Headquarters at 1am in the morning using a combination of the ParaJaegers highly secret JMW-110 Assault Glider-Gyrocopters (dropped in earlier to set out a landing area and landing lights for the main drop) and the JMW-100 and rather larger JMW-200 Gliders, the entire Battalion descended in silence on a drop zone within a mile of the targeted Divisional Headquarters. Their mission was to both eliminate the Divisional Headquarters and to capture or destroy nearby Red Army artillery batteries that could hold up the advance. The 4am attack on the Divisional Headquarters met immediate and ferocious, if uncoordinated, resistance and the Battalion found itself fighting Red Army line infantry. Casualties were heavy, but the Atholl Highlanders beat down an uncordimated Red Army defence and moved rapidly to secure their objectives and destroy the Divisional Headquarters, working from detailed maps prepared from Ilmavoimat reconnaissance photos.

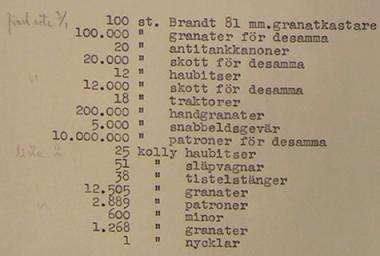

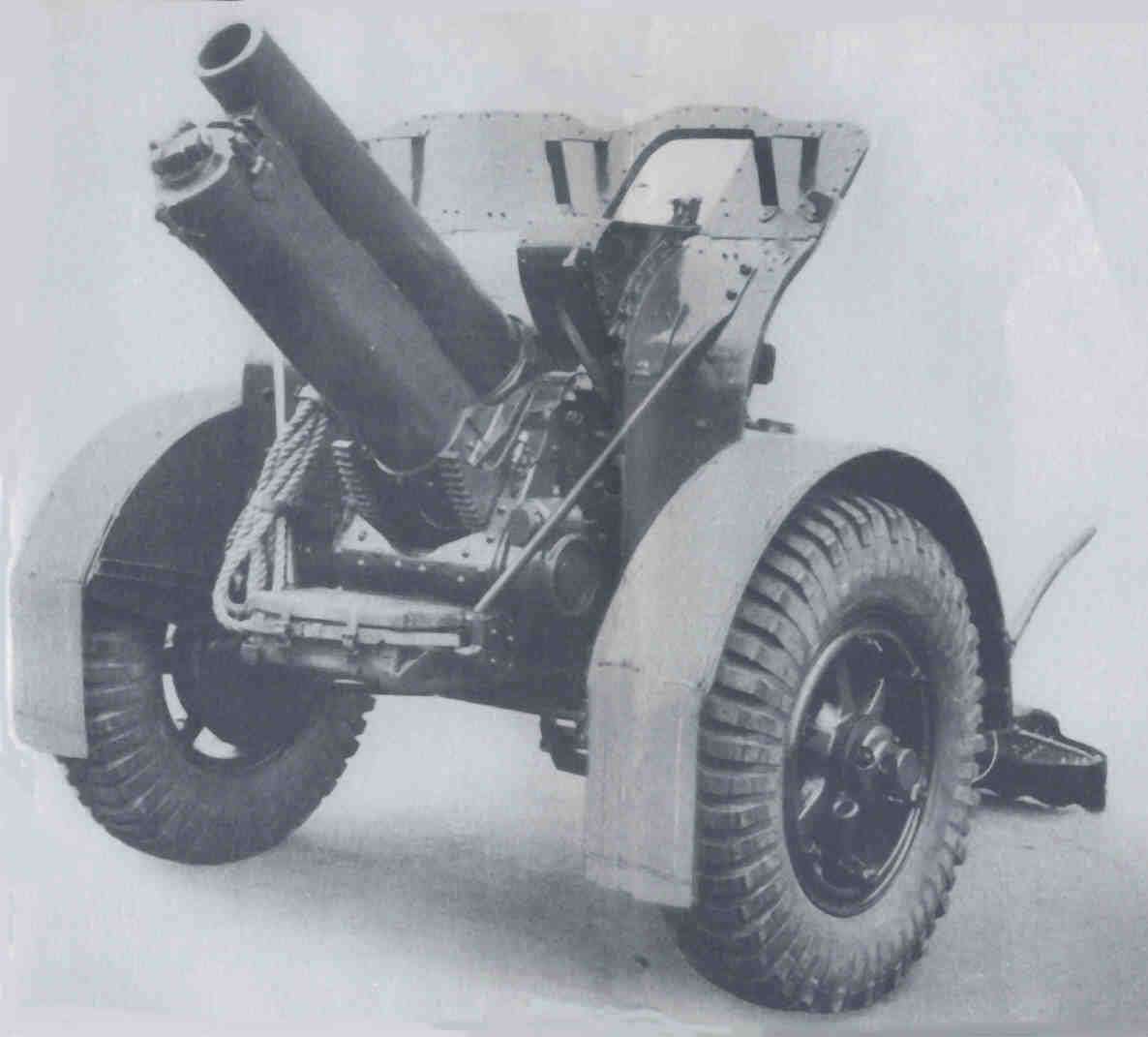

For Churchill, the high point of the fighting was the attack made by his Company on the Red Army Artillery Regiment. He organized his men into three parallel Platoon-sized columns and, since the heavy undergrowth ruled out any chance of a silent advance, sent them charging through the darkness shouting the Finnish Army battle cry of “"Hakkaa päälle!” that the Atholl Highlanders had enthusiastically adopted. The yelling not only minimized the risk of the Atholl Highlanders shooting each other in the gloom, but also confused the Russian defenders, to whom this fierce shouting seemed to come from all directions in the blackness of the night. The attack carried all its objectives and resulted in the capture of 36 x 152mm Howitzers together with all their ammunition stockpiles and most of the transport in an undamaged condition. The men of the Red Army Artillery Regiment were slaughtered piecemeal, with fierce but ineffective resistance. In the morning light, the position was found to be carpeted with Red Army dead.

Churchill himself was far in front of his troopers. Sword in hand, accompanied by a corporal named Ruffell, he had advanced as far as a large Divisional Supply Depot. Undiscovered by the enemy, he and Ruffell heard Red Army soldiers digging in all around them in the gloom. The glow of a cigarette in the darkness told them the location of a Russian sentry post. What followed, even Churchill later admitted, was “a bit Errol Flynn-ish.” The first Russian sentry post, manned by two men, was taken in silence. Churchill, his sword blade gleaming in the night, appeared like a demon from the darkness, ordered “Pуки Bверх!” (Hands Up) and got immediate results. He gave one Russian prisoner to Ruffell, then slipped his revolver lanyard around the second sentry’s neck and led him off to make the rounds of the other guards. Each post, lulled into a sense of security by the voice of their captive comrade, surrendered to this fearsome apparition with the ferocious mustache and the naked sword. Altogether, Churchill and Corporal Ruffell collected 42 prisoners, complete with their personal weapons. Churchill and his claymore then took the surrender of ten men in a bunch around the Supply Depot HQ. He and his NCO then marched the whole lot back to the Company HQ before detaching a Platoon to secure the Depot.

They were the only prisoners taken in the attack. He later had to dissuade Wingate from having them shot out of hand. “Wingate’s reason was we were behind enemy lines and couldn’t afford the men to guard prisoners. But as we were already being reinforced with a Finnish Battalion coming in on Gliders and we had Close Air Support on call and our own Artillery in range and we were expected the Finnish Army to arrive within the day I dissuaded him from this course of action. I’d always thought Wingate was rather a ruthless sort of chap and this convinced me completely. I wasn’t at all happy about the order, although of course if we had been in any danger I would have had them shot. As it was, after the War ended the Finns handed the Red Army prisoners back to the Russians and the NKVD of course had almost all of them shot, so in the long run there was no real difference for them.” The Red Army would again launch a number of confused and uncoordinated counter-attacks throughout the next day, all of which were driven off. As the advance elements of the Maavoimat broke through to the Atholl Highlanders position, Churchill greeted the advancing Finns with another tune on the bagpipes, one of his favorites – “Will Ye No Come Back Again.” Long after the end of the war, Churchill was pleased to hear that the Finnish account of the fighting and the relief of the Atholl Highlanders described his lonely piping as “the doleful sound of an unknown British musical instrument.”

“The doleful sound of an unknown British musical instrument.”

“Will Ye No Come Back Again”- the Atholl Highlanders picked up the somewhat mournful song from Jack Churchill and would often sing it in the aftermath of beating off yet another Red Army attack.

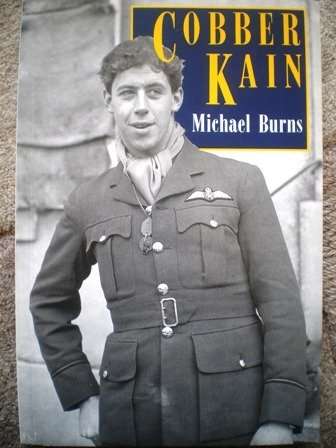

Photo sourced from: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/c ... rchill.jpg

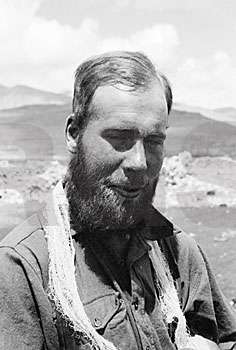

Major “Mad Jack” Churchill, CO “B” Company, Atholl Highlanders (Note the Maavoimat Parajaeger wings on the right shoulder of his uniform). Leading his unit into combat for the second time in Finland in Spring 1940, Churchill played “The March of the Cameron Men” on his bagpipes as his glider approached the landing site – near a Red Army Divisional Headquarters. He was determined to be the first man into action and was stowing his bagpipes when his glider touched down and two of his men pushed past him. He quickly leapt out and ran ahead, his sword in one hand and pistol in the other. The Company met disorganized resistance which was quickly overcome by the simple expedient of shooting every Red Army soldier in sight and overwhelming any attempt at serious resistance with instant attacks. In the course of the attack a hand grenade exploded and a fragment gashed Churchill’s forehead. The wound was painful and very obvious but not serious, and got him much sympathy when he visited Viipuri on a short leave after his Company returned to the rear to recover and regroup. Churchill later claimed that it began healing too quickly and had to be touched up with borrowed lipstick to keep the “wounded hero” story going for the remainder of his short leave.

Churchill would later lead “B” Company in a series of deep-penetration raids behind the Red Army lines, in the course of which he continued to carry his trademark Scottish broadsword slung around his waist and a longbow and arrows around his neck and his bagpipes under his arm. The raids allowed him to give full vent to his martial inclinations and he delighted in the destruction of Red Army supply depots and rear area units as well as in ambushes of Red Army units. Perhaps the highlight for Churchill was the overrunning and destruction of a major artillery depot in the Red Army rear. “It was enormous, just thousands and thousands of artillery shells and hardly any guards. It was so far in the rear they obviously weren’t expecting us and we took them by surprise, killed all the guards and then spent a day setting all the demolition charges. We were miles away when they went off and it was the biggest explosion I’ve ever seen, literally mind-boggling. And then on the way back we were following a road which we shouldn’t have done and we ran into a truckload of Red Army soldiers coming towards us. We didn’t want any noise so after we stopped the trucks we piled in and bayoneted the lot of them. We’d just finished when another truck came round the corner and we realized it was the lead truck of what seemed to be a Battalion of Red Army troops. So we started to shoot them up, charging on foot down the side of the trucks killing as many as we could before they got organized. I sent B/3 Platoon to cut through the forest and take them in the rear and at the same time we got on the radio and called in Close Air Support from the Ilmavoimat. The Henley’s turned up inside half an hour and just blew them away, I don’t think there were any survivors. We had quite a party when we got back to our own lines.”

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/c ... _sword.jpg

Jack Churchill (far right) leads men of “B” Company from a Finnish-built Higgins-designed Eureka boat on Lake Äänisen in an assault on Red Army positions, sword in hand.

Jack Churchill returned to Britain in late 1940 together with the remaining men of the Atholl Highlanders and promptly volunteered for the Commandoes. Training in Scotland with the Commandoes produced an unexpected dividend for Churchill. There he met Rosamund Denny, the daughter of a Scottish ship building baronet. They were married in Dumbarton in the spring of 1941, a happy marriage that would produce two children and last until Churchill’s death 55 years later. In 1941 he was second-in-command of a mixed force from 2 and 3 Commandos which raided Vågsøy, in Norway. The aim was to blow up local fish oil factories, sink shipping, gather intelligence, eliminate the garrison and bring home volunteers for the Free Norwegian Forces. Before landing, Churchill decided to look the part. He wore silver buttons he had acquired in France; carried his bow and arrows and once again armed himself with a broad-hilted claymore; and led the landing force ashore with his bagpipes. Although he was again wounded, the operation forced the Germans to concentrate large defensive forces in the area. For his actions at Vågsøy, Churchill received the Military Cross. After recovering, Churchill was appointed Lieutenant-Colonel commanding No 2 Commando which he took through Sicily (leading with his bagpipes into Messina) and then to the landings at Salerno in 1943.

Photo sourced from: http://www.commandoveterans.org/cdoGall ... alerno.jpg

Jack Churchill at Salerno, 15th Sept. 1943: Jack is nearest the camera, the hilt of is claymore above his haversack.

In 1944, he led the Commandos in Yugoslavia, where they supported the efforts of Tito's Partisans from the Adriatic island of Vis. A series of successful raids by Commandos and partisans hurt the Germans, and in May 1944, a more ambitious attack by British and Yugoslav personnel was planned on the German-held Yugoslav island of Brac. It was here that Jack Churchill’s luck at last ran out. The operation required attacks on three separate hilltop positions, dug in, mutually supporting, protected by wire and mines, and covered by artillery. Several Allied forces would have to work in cooperation. One of these, a reinforced Commando unit plus a large contingent of partisans, Jack Churchill would lead himself. While partisan attacks on the main German position got nowhere, 43 (Royal Marine) Commando went to the attack on the vital hill called Point 622. Pushing ahead in clear moonlight through wire and minefields, 43 Commando carried the hilltop but was forced to fall back with heavy casualties. Churchill now sent 40 Commando—also Royal Marines—in against the hill, and led them himself, playing the pipes. The leading troop went in yelling, shooting from the hip, and overran the German positions on 622.

But between casualties on the way up the hill and more casualties from very heavy German fire on the top, Churchill quickly found himself isolated with only a handful of defenders around him. There were only six Commandos on the hilltop, and three of those were wounded, two of them very badly. “I was distressed,” said Churchill with memorable understatement, “to find that everyone was armed with revolvers except myself, who had an American carbine.” Still, the little party fought on until the revolver ammunition was gone and Churchill was down to a single magazine for his carbine. A German mortar round killed three of his little party and wounded still another, leaving Churchill as the only unwounded defender on the hilltop. It was the end. Churchill turned to his pipes, playing “Will ye no come back again” until German grenades burst in his position and he was stunned by a fragment from one of them. He regained consciousness to discover German soldiers “prodding us, apparently to discover who was alive.”

Churchill would play his pipes one more time, at the funeral of the 14 Commandos who died on the slopes of Hill 622. He and his surviving men escaped killing by the Gestapo under Hitler’s “commando order” through the chivalry of one Captain Thuener of the Heer. “You are a soldier, as I am,” the captain told Churchill. “I refuse to allow these civilian butchers to deal with you. I shall say nothing of having received this order.” After the war, Churchill was able to personally thank Thuener for his decency and to help him stay out of the hands of the Yugoslav Communists. Churchill was flown to Sarajevo and then on to Berlin, there apparently being some thought that he was a relative of Winston Churchill. There is a story that on leaving the aircraft, he left behind a burning match or candle in a pile of paper, producing a fire and considerable confusion. During the inquiry that followed, Churchill innocently told a furious Luftwaffe officer that the army officer escorting Churchill had been smoking and reading the paper on board the aircraft. Churchill spent some time in solitary confinement, and in time he ended up in Sachsenhausen concentration camp. That infamous prison was only one more challenge to Churchill, however, and in September 1944, he and an RAF officer crawled under the wire through an abandoned drain and set out to walk to the Baltic coast. Their luck was not in, however, and they were recaptured near the coastal city of Rostock, only a few miles from the sea.

In time, they were moved to a camp at Niederdorf, Austria. Here, Churchill watched for another opportunity to escape, keeping a small rusty can and some onions hidden in his jacket in case a sudden opportunity should present itself. On an April night in 1945, it did. The chance came when the camp’s lighting system failed. Churchill seized the moment and walked away from a work detail, disappearing into the darkness and heading for the Alps and the Italian frontier. Liberating vegetables from Austrian gardens and cooking them in his tin can, he walked steadily south. Keeping off the roads, he crossed the Brenner Pass into Italy and headed for Verona, some 150 miles away. On the eighth day of his escape, hobbling along on a sprained ankle, Churchill caught sight of a column of armored vehicles. To his delight, their hulls carried the unmistakable white star of the United States Army. He managed to flag down one vehicle and persuade the crew that in spite of his scruffy appearance he was indeed a British colonel. As he later told his old friend and biographer, Rex King-Clark, “I couldn’t walk very well and was so out of breath I could scarcely talk, but I still managed a credible Sandhurst salute, which may have done the trick.”

Churchill was free but frustrated. The European war was almost over, and he had missed much of it, including the chance for further promotion and perhaps the opportunity to lead a Commando brigade. Nevertheless, hope sprang eternal. “However,” he said to friends, “there are still the Nips, aren’t there?” There were. And so Churchill went off to Burma, where the largest land war against Japan was still raging. Here, too, however, he met frustration, for by the time he reached India, Hiroshima and Nagasaki had disappeared in mushroom clouds, and the war abruptly ended. For a warrior like Churchill, the end of the fighting was bittersweet. “You know,” he said to a friend only half joking, “if it hadn’t been for those damned Yanks we could have kept the war going for another 10 years.” The abrupt departure of Japan from the war was a distinct disappointment to Churchill, especially since he had risen to the command of No 3 Commando Brigade in the Far East. Still, there were other brushfire wars still smoldering, and in November 1945, he reported home from Hong Kong, “As the Nips have double-crossed me by packing up, I’m about to join the team vs the Indonesians,” who were by then casting covetous eyes on Sarawak, Borneo, and Brunei. British and Commonwealth troops killed or expelled the invaders, but Jack missed this little war as well.

By the next year, he had transferred to the Seaforth Highlanders and then completed jump school, where, at 40, he qualified as a paratrooper. He made his first jump on his 40th birthday, and afterwards commanded the 5th (Scottish) Parachute Battalion, thus becoming the only officer to command both a Commando and a Parachute battalionHe took a little time off in 1946, this time for the movies. Twentieth Century Fox was making Ivanhoe with Churchill’s old rowing companion Robert Taylor and wanted him to appear as an archer, firing from the wall of Warwick Castle. Churchill took the assignment, flown off to the job in an aircraft provided by the movie company. In 1948 he ended up in Palestine as second-in-command of 1st Battalion, the Highland Light Infantry. Back in Britain, he was for two years second-in-command of the Army Apprentices School at Chepstow before serving a two-year stint as Chief Instructor, Land/Air Warfare School in Australia, where he became a passionate devotee of the surfboard.

Back in England, Churchill joined the War Office Selection Board at Barton Stacey and during this period he was the first man to ride the River Severn’s five-foot tidal bore and designed his own board. His last post was as First Commandant of the Outward Bound School. In retirement, however, his eccentricity continued. He finally retired from the army in 1959 but went right on working as a Ministry of Defense civilian overseeing the training of Cadet Force youngsters in the London District. One of his old friends wrote later that Churchill liked the job not only because of his association with the enthusiastic cadets, but also because the job gave him an office in Horse Guards at Whitehall, and a window from which he could watch troopers of the Household Cavalry mounting guard in a courtyard below him.In his last job he would often startle train conductors and passengers by standing up, opening the train window and throwing his attaché case out of the train window, then calmly resume his seat. He later explained that he was tossing his case into his own back garden so he wouldn’t have to carry it from the station.

He also devoted himself to his hobby of buying and refurbishing coal-fired steam launches on the Thames; he acquired 11, making journeys from Richmond to Oxford with Churchill decked out in an impeccable yachting cap and Rosamund giving appropriate sailing orders to her husband. He was also a keen maker of radio-controlled model boats, mostly warships, which he sold at a profit and which are now sought-after collectors’ items. He also took part in motor-cycling speed trials. Churchill passed away peacefully at his home in Surrey in the spring of 1996, but he left a legacy of daring that survives to this day.

His biography, “Jack Churchill: Unlimited Boldness” by Lieutenant-Colonel Rex King-Clark is not so easily available second-hand but if you can get it, its well worth a read, even though its fairly short at only 28 pages.

As it turned out, “Mad Jack” Churchill did leave something of a legacy in Finland. The Atholl Highlanders had worked closely on the Karelian Isthmus with the 21st Pansaaridivisoona and at some stage the tankers had acquired somewhat of a liking for the bagpipes, eventually forming their own Pipe Band. In the video below, we can see the Division’s Pipe Band leading a Maavoimat parade through one of the few areas of Königsberg (in East Prussia) still standing after the RAF bomber raids of 1944. This parade was shortly after the city fell to the Maavoimat. (Although Hitler had declared Königsberg an "invincible bastion of German spirit", the German military commander of Königsberg, General Otto Lasch, had surrendered the city and the foreces under his command without a fight. For this act, Lasch was condemned to death in absentia by Hitler). Post capture by the Maavoimat, Königsberg would become a haven for German refugees in East Prussia and Poland and the location of a major Maavoimat POW and internment camp for captured members of the German military. Königsberg would also be a major bone of contention in the post-war negotiations as the ruling Soviet triumvirate wanted a year-round ice-free harbor.

Elements of the 21st Pansaaridivisoona parading through Königsberg in early 1945, led by the Maavoimat’s one and only Divisional Pipe Band. Sadly, in the post-war years, this Military Pipe Band has disappeared and the only traces now of the Bagpipes in Finland are a small number of civilian pipe bands.

Hamina Tattoo - Helsinki Pipes and Drums – a last trace of the Atholl Highlanders in Finland

Post-War Note: At the end of World War II in 1945, the Soviet Union demanded the annexation of the city of Königsberg and the surrounding areas of East Prussia as as part of the Russian SFSR, pending the final determination of territorial questions at the peace settlement as agreed upon by the Allies at Yalta. At the Potsdam Conference, the Conference examined a proposal by the Soviet Government regarding Königsberg and East Prussia. The President of the United States and the British Prime Minister declared that they would support the proposal of the Conference at the forthcoming peace settlement and stated that they agreed in principle to the proposal of the Soviet Government concerning the ultimate transfer to the Soviet Union of the city of Koenigsberg and the area adjacent to it as described above, subject to expert examination of the actual frontier.

The Finnish and Polish Governments stated in their turn that East Prussia was in the Finnish Zone of Control and no such agreement would be recognised by Finland or Poland, just as no movement of the eastern Polish border would be countenanced and just as the Soviet claims to the Baltic States as a result of the agreements signed under duress in 1940 were not recognised. Inevitably this led to a long period of tension in the immediate aftermath of WW2 and into the years of the Cold War. As a result of the Finnish refusal to back down to the Soviet Union, and the terrifying reputation of the Finnish military at the time (including their willingness to take on Red Army combat formations many times their size and annihilate them, as had occurred a number of times in the last few months of the war), the post-war delineation of Baltic borders resulted in the independent state of Baltic Prussia being formed and recognised, with its capital being Königsberg. A magnet for German refugees from the rest of Eastern Europe and from Poland, Baltic Prussia became a hub for the rapid post-war recovery of the Baltic States and today is a small but prosperous state closely aligned with Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia and Finland.

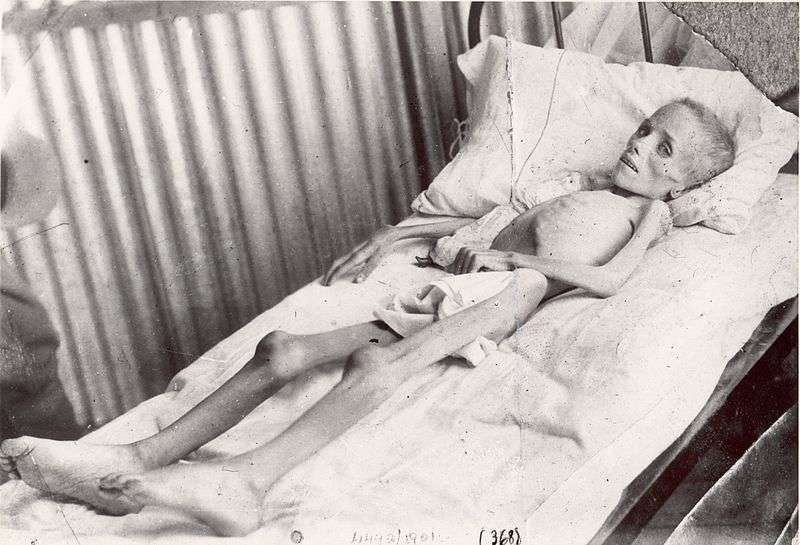

OTL Note: Many people fled Königsberg ahead of the Red Army's advance after October 1944, particularly after word spread of the Soviet atrocities at Nemmersdorf. In early 1945 Soviet forces under the command of the Polish-born Soviet Marshall Konstantin Rokossovskiy besieged the city. In Operation Samland, General Baghramyan's 1st Baltic Front, now known as the Samland Group, captured Königsberg in April. [On April 9 — one month before the end of the war in Europe — the German military commander of Königsberg, General Otto Lasch, surrendered the remnants of his forces following a three-month-long siege by the Red Army. For this act, Lasch was condemned to death in absentia by Hitler. At the time of the surrender, military and civilian dead in the city were estimated at 42,000, with the Red Army claiming over 90,000 prisoners. About 120,000 survivors remained in the ruins of the devastated city. These survivors, mainly women, children and the elderly and a few others who returned immediately after the fighting ended, were held as virtual prisoners until 1949. A majority of the German citizens remaining in Königsberg after 1945 died of either disease, starvation or revenge driven ethnic cleansing. The German population was either deported to the Western Zones of occupied Germany or into Siberian labor camps, where about half of them perished of hunger or diseases The remaining 20,000 German residents were expelled in 1949–50. Resettled by Russians, Russian Kaliningrad and the surround area is now a blighted and impoverished region with very few redeeming features.

Next Post: Further British Aid for Finland