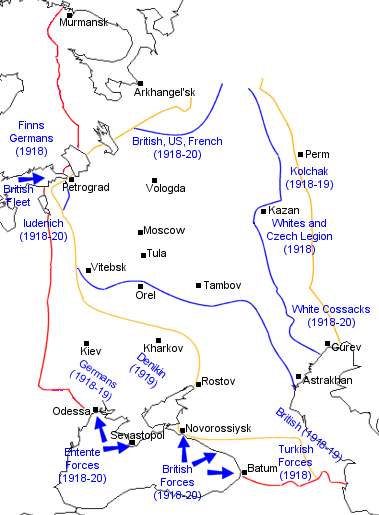

In addition to the expeditions into Karelia, there were a number of other conflicts involving Finnish volunteers in the years between 1918 and 1922.

The Petsamo Excursions of 1918 amd 1920

The idea of these expeditions was to bring Petsamo officially under Finnish control, and then to establish and place border guards on the Finnish - Russian border in order to solidify the Finnish claim to Petsamo, which was based on the promise of Czar Alexander II, who had undertaken to award Petsamo to Finland in exchange for the territory of the Siestarjoki / Sestroryetsk weapons factory on the Karelian Isthmus. In 1918, both Finnish Whites and Reds were interested in the Petsamo area. The Finnish Reds (People’s Commissar George Sirola) negotiated over Petsamo with the Bolsheviks, while the Finnish Whites sent an expedition to lay claim to the area.

The 1918 expedition: In the spring of 1918, the Finns sent two expeditions, which later joined together. One of these two expeditions had a strength of about 100 men and was lead by Dr. Thorsten Renvall (brother of Senator Heikki Renvall, who was the leader of the Finnish Senate aka the Finnish Government in Vaasa during Civil War). The other expedition was financed by businessmen, and was known as Lapin Rakuunat (The Dragoons of Lapland) and was also lead by a doctor - Onni Laitinen. In May of 1918 the two expeditions arrived together at Petsamo. The British North Russia Expeditionary Force based in Murmansk considered these Finnish expeditions a threat, since they were worried that the Germans might arrive in the area after the Finns and take over it for their own purposes (the major concern of the British was that the Germans might use Petsamo as a Submarine base, targeting British shipping to Murmansk and Arkhangelsk, which had become major transit ports for the transhipment of military equipment and munitions to Russia for use in fighting the Germans on the Eastern Front).

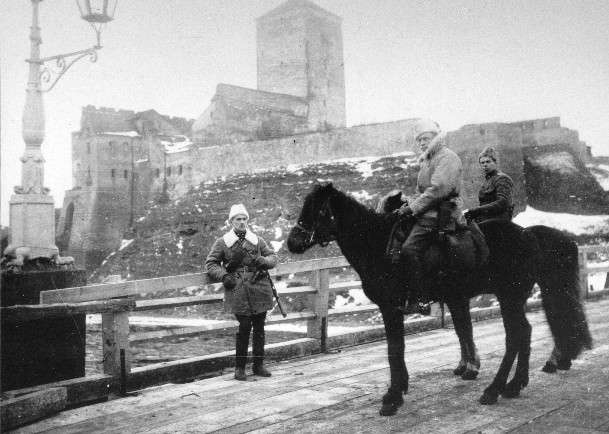

Leaders of the first Petsamo Expedition – Rovaniemi: 1918. Pictured left to right, front (in the white hat and coat): Thorsten Renvall (CO), Johan Bäckman, Julius Niemura, Jalmari Ruokokoski. Arvi Vinberg and Hjalmar Mehring. Rear: Ellen Id, Elvi Halle, Helge Aspelund, Ester Fogelberg, who is holding the flag created for the expedition by the artist, Jalmari Ruokokoski.

Leaders of the first Petsamo Expedition – Rovaniemi: 1918. Pictured left to right, front (in the white hat and coat): Thorsten Renvall (CO), Johan Bäckman, Julius Niemura, Jalmari Ruokokoski. Arvi Vinberg and Hjalmar Mehring. Rear: Ellen Id, Elvi Halle, Helge Aspelund, Ester Fogelberg, who is holding the flag created for the expedition by the artist, Jalmari Ruokokoski.

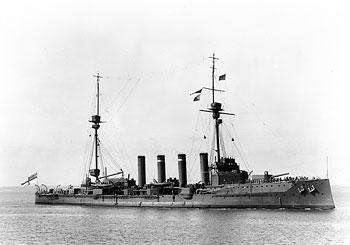

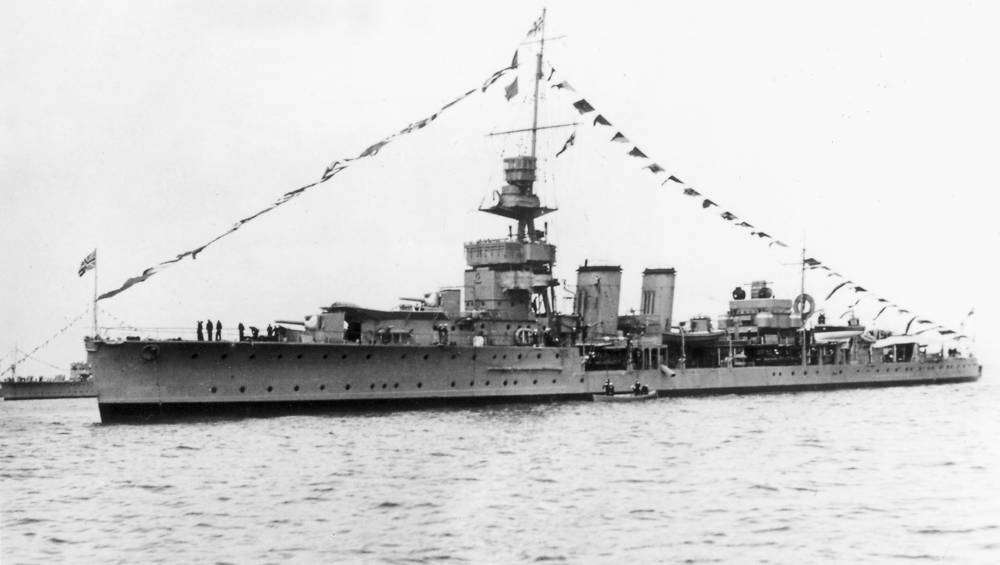

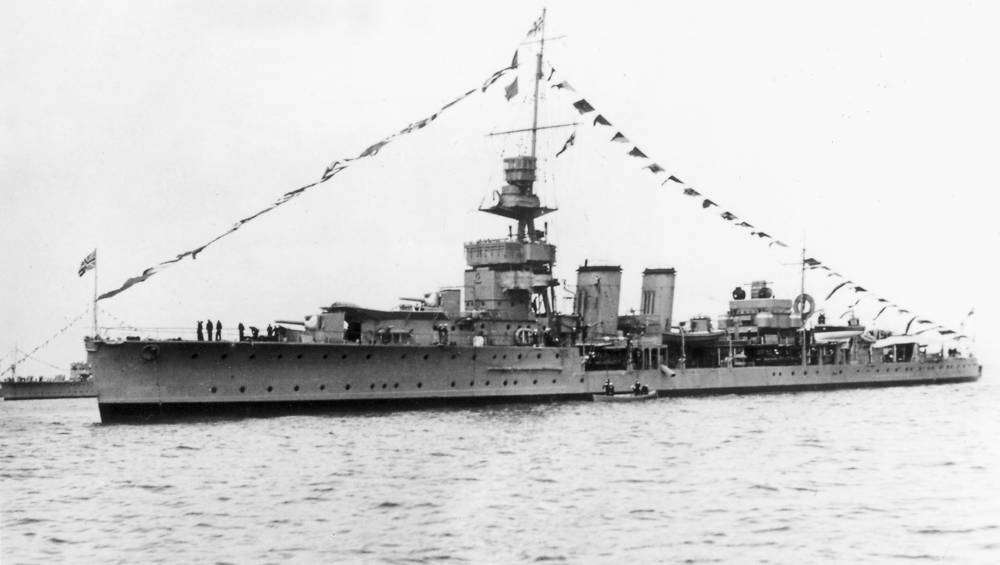

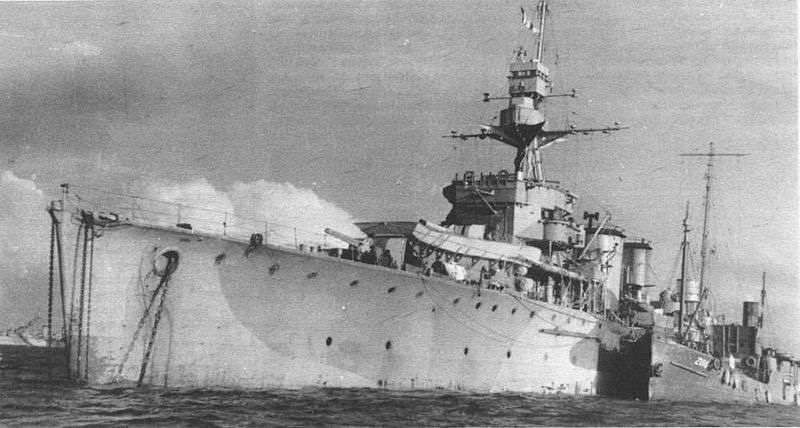

On the 3rd of May 1918, HMS Cochrane brought troops to Petsamo (100 Royal Marines, 40 sailors and 40 Russian Reds, commanded by Captain Brown). The Finnish Expeditionary Force fought the British for three days until the 6th of May, when HMS Cochrane brought in reinforcements (35 additional soldiers, five Lewis machineguns plus sailors, and also landed a 12-pound artillery gun as additional support). On the 10th of May the British captured Petsamo and succeeded in repelling the Finnish counter-attack. After this, the British replaced their troops with 200 Serbian soldiers (The Allies were using Serbian soldiers, among others, in the North Russian Expeditionary Force). The Finnish expeditions headed back south. Finland and Britain exchanged diplomatic notes and Britain advised that it didn't have anything against Finnish demands concerning Petsamo. The Finnish force consisted contained mostly civilians (not such a surprise considering the timing – the Finnish Civil War ended officially on the 15th of May).

HMS Cochrane

HMS Cochrane

The 1920 expedition: This expedition in the spring of 1920 consisted of about 60 men and was led by Kurt Martti Wallenius (who was better known later as one of the leaders of the Lapua movement and then as the commander of the Lapland Group during the Winter War). From the 16th of April the expedition was lead by Major Gustaf Taucher. The Russian Bolsheviks sent a ski battalion created in Murmansk to fight against it. This expedition also failed and was forced to return south tp Finnish territory. Despite these military defeats, the Treaty of Tartu agreed that the Petsamo area would become part of Finland.

The Estonian War of Independence Nov 1918 to Feb 1920

Estonia had been subject to some sort of foreign hegemony since the 13th century and had been a province of Imperial Russia since 1710. Then, amidst the turmoil of World War I and the Russian Revolution, chaos ensued: foreign armies (Bolshevik, White Russian and German) came and went. Estonia sought independence and between 1918 and 1920 fought a war to achieve this. The war attracted a diverse range of participants. Estonian efforts to achieve independence were augmented by White Russian soldiers fighting to restore the Russian Empire, by Finnish, Swedish, and Danish volunteers, and by a British naval presence. Estonia also fought a bloody battle on its southern border against a Baltic German military force. There was a great deal of battlefield realignment, and front lines moved dramatically as each side’s fortunes rose and fell: at one point, Soviet forces came within 35 kilometers of Tallinn; at another, Estonian forces conquered Pskov and got quite close to St Petersburg (then called Petrograd).

By the time it was over, the 14-month war had claimed 3,588 Estonian lives and left 13,775 Estonians injured. Estonian and Soviet Russian negotiators met in Tartu, Estonia’s second-largest city, to negotiate peace. In the resulting Tartu Peace Treaty, signed on February 2nd, 1920, Soviet Russia recognized Estonian independence and forever renounced claims on Estonian territory. The Soviets also agreed to pay Estonia restitution in the amount of 15 million gold rubles. But between the Bolshevik Revolution and the Taru Peace Treaty, a great deal had occurred.

In November 1917, on the disintegration of the Russian Empire, a diet of the Autonomous Governorate of Estonia, the Estonian Provincial Assembly, which had been elected in the spring of that year, proclaimed itself the highest authority in Estonia. Soon after, the Bolsheviks dissolved the Estonian Provincial Assembly and temporarily forced the pro-independence Estonians underground in the capital Tallinn. A few months later, using a moment of time between the Red Army's retreat and the arrival of the Imperial German Army, the Salvation Committee of the Estonian National Council, Maapäev, issued the Estonian Declaration of Independence in Tallinn on February 24, 1918 and formed the Estonian Provisional Government. This first period of independence was extremely short-lived, as the German troops entered Tallinn on the following day. The German authorities recognized neither the provisional government, nor its claim for Estonia's independence, viewing them as a self-styled group usurping the sovereign rights of the (Germanic) Baltic nobility.

However, after the capitulation of Imperial Germany in November 1918, the situation in the Baltic became increasingly chaotic. The Russian Empire had collapsed and was in the throes of Civil War. Estonia, Latvia amd Lithuania has been granted nominal independence by the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, but Lenin had also declared: "The Baltic must become a Soviet sea," and unleashed his forces across the region. German garrisons held many of the major cities, few of them were inclined to obey their government's order to return home. And in Latvia and Estonia, White Russian forces were gathering, bent on retaking the Bolshevik stronghold of Petrograd and rebuilding the Russian empire. In Estonia, the representatives of Germany formally handed over political power to the Estonian Provisional Government. On 16 November 1918, the Estonian provisional government called for voluntary mobilization and started to organize the Estonian Army, with Konstantin Päts as Minister of War, Major General Andres Larka as the chief of staff, and Major General Aleksander Tõnisson as commander of the Estonian Army, initially consisting of one division.

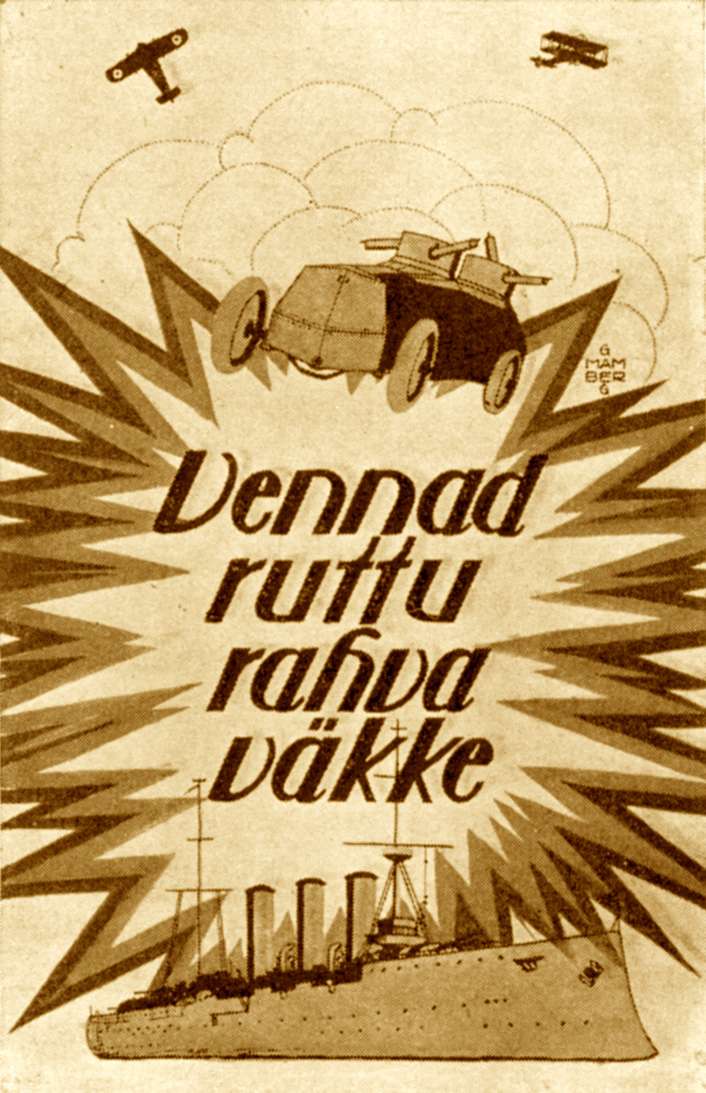

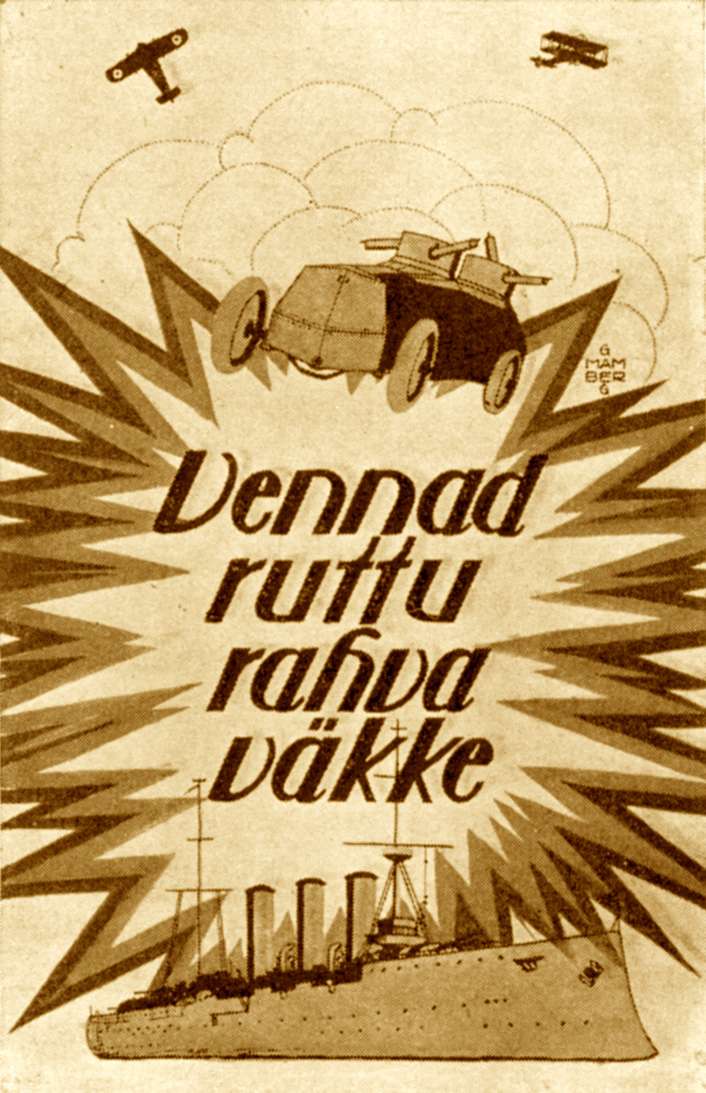

Brothers, Hurry to Join the Nation's Army!: Estonian Army Recruiting poster in 1918

Brothers, Hurry to Join the Nation's Army!: Estonian Army Recruiting poster in 1918

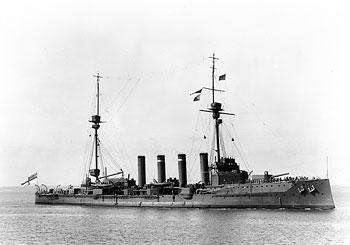

The Estonian War of Independence began a few days later, when on 28 November 1918 the Bolshevik 6th Red Rifle Division attacked units of the Estonian Defence League (which partly consisted of secondary school pupils) and the German Infanterie-Regiment Nr. 405 who were defending the border town of Narva. The Red’s, with their force of 7,000 infantry, 22 field guns, 111 machine guns, an armored train, 2 armored vehicles, 2 airplanes, and the Bogatyr class cruiser Oleg supported by 2 destroyers captured Narva almost immediately (on the 28th of November 1918). The Red force then advanced to the Tapa railway junction by Christmas Eve, later advancing to 34 kilometers from the capital Tallinn. Estonian Bolsheviks declared the Estonian Workers' Commune in Narva. The German Infanterie-Regiment Nr. 405 withdrew westwards. At the same time, the 2nd Novgorod Division opened a second front south of Lake Peipus with a force of 7000 infantry, 12 field guns, 50 machine guns, 2 armored trains, and 3 armored vehicles. The 49th Red Latvian Rifle Regimen took Valga railway junction on 18 December and Tartu town on Christmas Eve. By the end of the year, the 7th Red Army controlled Estonia along a front line 34 kilometers east of Tallinn, west from Tartu and south of Ainaži.

Front line Estonian Soldiers in the trenchs fighting for independence

Front line Estonian Soldiers in the trenchs fighting for independence

The Red Army attack starting at the end of 1918 hit Estonia in an extremely difficult situation. The administration and army of the young republic were only then being formed, and had very little experience. The army lacked sufficient weapons and equipment. Food and money were scarce and the population of the towns were in danger of starvation. Although the majority of the population did not support the Bolsheviks, their faith in the survival of the national state was not high. People did not believe that the Republic of Estonia would be able to resist the attacks of the Red Army. The Estonian government nevertheless decided to oppose the Bolshevist aggression, hoping for help from the Western countries (i.e. the former Russian allies in World War I) and Finland.

Opposing the two Red Army Divisions was an Estonian military force consisting of 2,000 men equipped with light weapons and about 14,500 poorly armed Estonian Defence League (Home Guard) soldiers. The end of November 1918 also saw the formation of an Estonian Baltic battalion, made up of volunteers belonging to Estonia's Baltic German minority. This battalion was thus one of the first fighting units of the Estonian Army, and stayed loyal to the authorities of the republic, unlike the Landeswehr in neighbouring Latvia. External help was essential, but it would have been insufficient without Estonia’s own decisive steps. Active organisational work was conducted, and new army units were formed. On 23 December 1918, the energetic Colonel Johan Laidoner was appointed Commander in Chief of the Estonian armed forces, and recruited 600 officers and 11,000 volunteers by 23 December 1918. He reorganized the forces by setting up the 2nd Division in Southern Estonia under the command of Colonel Viktor Puskar, along with commando type units, such as the Tartumaa Partisan Battalion and Kalevi Malev. At the first opportunity he planned a counter-attack and forced the Red Army out of Estonia.

Colonel Johan Laidoner, Commander in Chief of the Estonian armed forces

Colonel Johan Laidoner, Commander in Chief of the Estonian armed forces

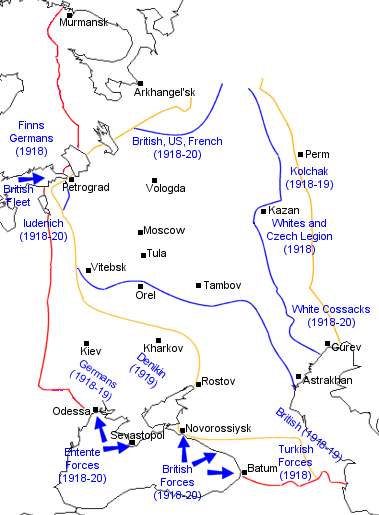

Meanwhile, the British government had been uncertain how to handle the unstable situation in the Baltic. The British agreed with the principle of supporting the newborn states in their independence and were now opposed to the Bolshevik’s, in general supporting White Russian and Independence movements throughout the former Russian Empire.

But the British, after four years of carnage in France, feared the political fall-out a prolonged infantry campaign in Russia would cause. Spurred by the First Sea Lord, Admiral Wester "Rosy" Wemyss, a man who believed in extending the "freedom of the seas" principle to the Baltic, the British Government decided to send a naval task force "to show the British flag and support British policy as circumstances dictate." On Nov. 22 1918, the Sixth Light Cruiser Squadron - five light cruisers and nine destroyers plus supporting vessels - sailed for the Baltic under the command of Rear-Admiral Edwin Alexander-Sinclair. First blood was soon shed: the squadron was passing northwest of Saaremaa, heading for Tallinn, when the cruiser Cassandra struck a German mine and sank with the loss of eleven hands. It was an ill-omened start, but the British soon recovered.

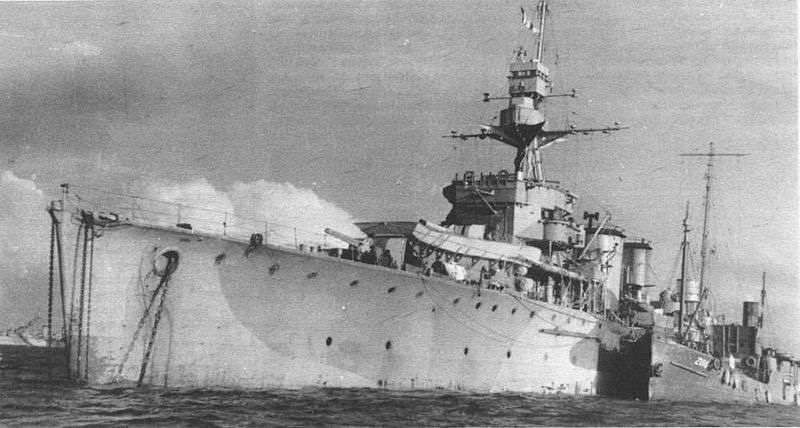

The flagship of British Admiral Kelly in Tallinn harbour. The Royal Navy took part in the Estonian War of Independence from the end of 1918, and was a considerable help in securing victory for the Estonian Army. The extensive British assistance was not, however, totally selfless — it was also an attempt to keep Estonia in an anti-Bolshevist coalition, which in the end did not succeed; the separate peace treaty of the Republic of Estonia with the Soviet Union caused much dissatisfaction in Western countries

The flagship of British Admiral Kelly in Tallinn harbour. The Royal Navy took part in the Estonian War of Independence from the end of 1918, and was a considerable help in securing victory for the Estonian Army. The extensive British assistance was not, however, totally selfless — it was also an attempt to keep Estonia in an anti-Bolshevist coalition, which in the end did not succeed; the separate peace treaty of the Republic of Estonia with the Soviet Union caused much dissatisfaction in Western countries

The British intervention had some immediately beneficial impacts on the Estonian fight for independence. On arrival at Tallinn on 31 December 1918, the Squadron delivered 6500 rifles, 200 machine guns and 2 field guns to the Estonian Army. Soon after reaching Tallinn they sailed again, steaming to Narva to bombard the Bolshevik positions there. Their actions infuriated Trotsky, who ordered: "They must be destroyed at any cost." On Dec. 26 1918 a Soviet task force left the Kronstadt naval base. One destroyer was sent to Tallinn to lure the British into an ambush, but when the British left harbor the destroyer began firing so wildly that it wrecked its own charthouse, concussed its helmsman and ran aground, signaling "All is lost. I am pursued by the English." By the end of the night two Soviet destroyers (the Spartak and the Avotril) had been captured (and were then donated to the Estonian navy, who renamed then Vambola and Lennuk), and the commissar of the Soviet fleet, F.F. Raskolnikov, had been found hiding under 12 sacks of potatoes and taken prisoner.

Estonian Destroyer Vambola (ex Spartak)

Estonian Destroyer Vambola (ex Spartak)

Viron Avustamisen Päätoimikunta / Committee to Aid Estonia

Meanwhile, in addition to assistance from the British, Estonia also obtained assistance from Finland. Estonia had made a number of requests for help to Finland in 1918 and public support for the provision of assistanc to Estonia (which linguistically and culturally is closely related to Finnish) was growing within Finland. On December 5th, 1918 Finland delivered 5000 rifles, 50 machineguns and 20 field guns together with ammunition. In addition, Finnish women’s groups organised clothing, bandages and medicine for export to Estonia.

Within Estonia, the situation continued to worsen through December and in Finland, right-wing newspapers were increasingly strident in their calls to assist Estonia. The Viron Avustamisen Päätoimikunta was founded on the 15th of December 1918 by Senator Oscar Wilho Louhivuori. Louhivuori was elected chairman of the Committee in Helsinki on the 20th December 1918, the Vice Chairman was Santosh Ivalo. Other members included figures with significant political and social influence within Finland, with representatives from all political parties except the Social Democrats. The committee’s main task was to organise the recruitment of volunteers for Estonia, for which permission was receieved from the Government and from the Regent (CGE Mannerheim).

Recruitment points were set up across the country and an agreement was reached with the Estonian Government on 18th December 1918 that a total of 2000 Volunteers would be sent, formed into two different volunteer forces. The leaders of these two forces were to be the Swedish Major Martin Ekström and Estonian Colonel Hans Kalm (both of whom had served in the White forces in the Finnish Civil War).

Hans Kalm

Martin Ekstrom

The Finnish government gave overall command of the Finnish Volunteers to Lieutenant General Martin Wetzer. The Committee registered a total of 10,000 volunteers through the recruiting points that had been set up, but of these only 4,000 were sent to Estonia (a number which was, however, twice the number of volunteers originally agreed between the two countries). It was also agreed however that if the situation in Estonia should further worsen, the remaining “reserve” of 6,000 volunteers would be sent. Of the 4,000 volunteers, almost all ended up fighting at the Front. The committee also arranged for other foreign volunteers to go to Estonia, notably a group of Swedish Volunteers and a further group of 175 soldiers and 16 Officers from Denmark (the Danish volunteers arrived in Helsinki from Copenhagen on 1 April 1919 and on 3 April arrived in Tallinn. The Danish volunteers fought in southern Estonia and northern Latvia, and many were decorated with various Estonian military medals. The commander of the Danes, Richard Gustav Borgelin, was promoted to lieutenant colonel for his services rendered in the War of Independence, and was given the manor of Maidla in recognition of his services.

Danish Volunteers in Estonia

Danish Volunteers in Estonia

The Swedish volunteer unit to support the Republic of Estonia in the Estonian War of Independence under the command of Carl Mothander was formed in Sweden in early 1919. In March 1919, 178 volunteers took part in scout missions in Virumaa. In April, the company was sent to the Southern front and took part of the battles near Pechory. By May 5 there was 68 men left in the company. On May 17, the company was disbanded by the order of the Estonian Minister of War. Some of the volunteers returned home in Sweden, some joined the Estonian Army, some the Danish volunteer unit. Other commanders of the Swedish volunteers in Estonia included C.G. Malmberg and L. Hällen

Major Carl Axel Mothander, Commander of the Swedish volunteers in the Estonian War of Independence (where he was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel)

Major Carl Axel Mothander, Commander of the Swedish volunteers in the Estonian War of Independence (where he was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel)

The start of the war had not been successful for Estonia. On 29 November 1918, the Estonian Workers’ Commune was declared as an independent Soviet Estonian Republic, in occupied Narva. This was essentially a Soviet Russian puppet state, established in order to present the events in Estonia as a civil war. At the same time underground communist agitators continued their subversive activity in the Estonian rear and in the army throughout the War of Independence. The militarily more numerous Red Army had managed to conquer about half of mainland Estonia by early January 1919. Only about 30 km separated them from the capital, Tallinn. BUT … on 2 January 1919, a Finnish volunteer unit of 2000 men arrived in Estonia, escorted and partially transported by a Royal Navy Baltic detachment, incidentally at the same time as other Finnish volunteer units were fighting against British-sponsored forces in East Karelia (proof of the confused situation and political complexities in the Baltic and on the periphery of the now-imploded Russian Empire).

Finnish volunteers arrive in Tallinn Estonia in December 1918 – these consisted of two volunteer units, Pohjan Pojat ("Sons of the North") and I Suomalainen Vapaajoukko (Ist Finnish Volunteer Corps).

Finnish volunteers arrive in Tallinn Estonia in December 1918 – these consisted of two volunteer units, Pohjan Pojat ("Sons of the North") and I Suomalainen Vapaajoukko (Ist Finnish Volunteer Corps).

Things now took a sudden turn for the better – on 7th January 1919 the now reorganized Estonian troops (15,000 men), together with the Finnish volunteers began a counter-offensive. Within three weeks all of Estonian territory was liberated from the Bolsheviks. A significant role was played by the volunteer units, the highly motivated armoured train crews, and the Julius Kuperjanov Battalion (Julius Kuperjanov was an Estonian who had graduated from the Tartu Teachers’ College in 1914. In 1915 he was conscripted into the Russian Army, completing the School of Ensigns and served as CO of an infantry regiment’s recconnaisance unit. In late 1917 he joined the national armed forces of Estonia. During the German occupation in 1918 he helped to organise secret military groups that were to form the basis of the Estonian armed forces once the German occupation was over.

In November 1918 Kuperjanov was appointed the head of the Defence League in Tartu County. After the War of Independence had started, he assembled a battalion in December 1918 which took his name – the Kuperjanov Partisan Battalion. In the January 1919 battles he stood out for his brave, energetic and successful actions. Kuperjanov also demanded strict discipline, not allowing his men any alcohol or playing cards. On 31 January 1919 Kuperjanov was fatally wounded at Paju Manor near Valga when he led his men in the attack. In the Republic of Estonia in the twenties and thirties he posthumously became a national hero, a paragon of bravery and self-sacrifice. The regiment formed by Kuperjanov demonstrated an excellent fighting spirit throughout the rest of the War of Independence, and a battalion bearing his name has been restored in today’s Estonian army).

Julius Kuperjanov

Julius Kuperjanov

An added factor in the Estonian success was that both the Estonian Army and the Finnish volunteers supporting the Estonian Army had the open support of both the Finnish Government and of the Royal Navy task force operating in the Baltic at the time (now under the command of Rear-Admiral Sir Walter Cowan, who had replaced Sinclair in January 1919). And unlike in Eastern Karelia, the Finnish volunteer forces achieved major successes in the fighting in Estonia, Western Ingria and Northern Latvia. The 1st Suomalainen Vapaajoukko captured Narva shortly after their arrival in Estonian in an amphibious assault (another operation supported by the Royal Navy) to the rear of the Red Army units - Trotsky himself was reportedly inside the city organizing the defense at the time the Finns stormed the city in a surprise attack. The defense collapsed, and Trotsky managed to get out before being captured.

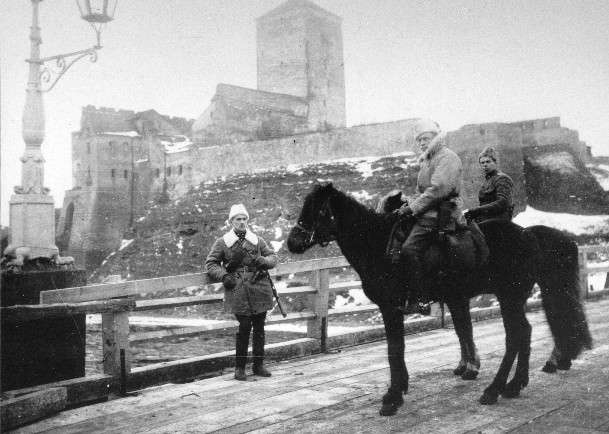

Lt. Eskola of 1st Suomalainen Vapaajoukko in Narva

Lt. Eskola of 1st Suomalainen Vapaajoukko in Narva

In February 1919 the Estonian government and army command set the military objective as being push the frontline as far from Estonia’s borders as possible. To this end they hoped that the Russian Whites (who had formed the Northern Corps - later the North-Western Army) would come to power in north-western Russia and the local nationalists in Latvia. In February 1919, as part of an agreement with the Latvian government, Latvian troops were formed in Estonia. Repeated attempts by the Estonian army to push the Red Army out of Estonia and fight the war in Russia and Latvia failed until May 1919, when Estonian troops together with the Northern Corps started an offensive towards Petrograd, pushed the frontline beyond the borders of Estonia and conquered a large territory east of Lake Peipsi. Forcing the enemy out of the country increased faith in the authority of the state, and enabled a further mobilisation that was crucial in continuing to fight the much larger Red Army. At the same time the Red Army had considerably supplemented its forces fighting against Estonia (between February and May, 6-8 percent of the Red Army forces or about 80,000 men were active on the Estonian Front) and carried out their own (unsuccessful) offensives.

In May the Estonian Army consisted of about 75,000 men, by the end of the year the number had increased to 90,000 – and this, combined with the new frontline beyond the borders, considerably reduced the danger of another Bolshevik invasion (in August, however, the troops retreated in order to protect the Estonia’s borders). Another key factor in the continuing success of the war was the foodstuffs, military equipment and weapons provided by Great Britain and the USA throughout 1919. Ongoing communist propaganda was seriously undermined by the revelations about the mass murders committed by the Bolsheviks while they had temporarily held power (among others, they had killed the Estonian Orthodox bishop Platon in Tartu). On 23 April 1919 the Estonian Constituent Assembly gathered in Tallinn. Its greatest achievement was the adoption of a Constitution and of land reform legislation. On the basis of the latter, a radical land reform program was carried out in 1920, mainly aiming to nationalise the lands of the German-owned manors and to distribute this land to the peasants, especially those who were takingt part in the War of Independence.

To a certain degree, the radical character of the land act was influenced by the so-called Landeswehr War waged in June and July 1919. In the course of that war, Estonian troops defeated the German army group based in Latvia and headed by Major-General Rüdiger von der Goltz, which consisted of many representatives of the Baltic German nobility from Latvia and Estonia. As a result of the Landeswehr’s defeat, the government of Kārlis Ulmanis came to power in Latvia, and Estonia now enjoyed a friendly neighbour to the south. As eastern Latvia was still occupied by the Red Army and the army of the Latvian Republic needed some organisation, the Estonian military command partly undertook the protection of the front there (until December 1919).

For the British, the situation in the Baltics had been complicated by the arrival of German Major-General Rudiger von der Goltz, and for the whole of 1919, Rear-Admiral Cowan's greatest challenges were to keep the Soviet fleet penned in Kronstadt and to stop the Germans overrunning the Baltics. His success was spectacular. The Soviet fleet had been reorganized following the loss of its two destroyers, and Trotsky had given the blunt instruction: "The Revolution must put the British fleet out of action." At first, fortune favored him: mines damaged the British cruiser Curacoa and sank the submarine L-55 and the minesweepers Myrtle and Gentian with the loss of over 50 lives. But despite these losses, the British managed to keep the Soviet navy from intervening in Estonia's war for independence, but failed to cause material harm until June 1919.

Major-General Rudiger von der Goltz

Major-General Rudiger von der Goltz

In that month, a single 40-foot coastal motor boat commanded by Lieutenant Augustus Agar (based out of Finland) penetrated the Kronstadt minefield and sank the cruiser Oleg. The action inspired Cowan, and on Aug. 17 he sent eight CMBs into Kronstadt. These small motorboats, armed only with torpedoes and machine guns, entered the main harbor basin and sank the Soviet fleet's two chief battleships and a store-ship. In the hail of fire that followed, three CMBs were sunk with the loss of 15 lives; but as Cowan commented of the Soviet fleet: "Nothing bigger than a destroyer ever moved again." Although a Soviet submarine later sank one British destroyer and a mine sank another, the Soviet naval threat to Estonia's flank was permanently lifted.

In Latvia, meanwhile, the situation was more complex. The largest armed force there was Goltz' German army, and Goltz was bent on conquest. To further his dream he repeatedly sabotaged the creation of a Latvian army, arranged a Baltic German coup, built a wall along Liepaja quay to keep Latvians and British apart (the British waited until the wall was finished, then simply moved their ships around it) and accused Karlis Ulmanis of having Bolshevik sympathies. The Latvian leader took shelter on the Latvian ship SS Saratov, and for the next few months his government lived under the protection of the Royal Navy's guns. When Goltz was forced to resign in September 1919, he was replaced by the Russian adventurer Paul Bermondt-Avalov, whose army promptly attacked Riga.

Pavel Bermondt-Avalov

Pavel Bermondt-Avalov

Latvia's nascent army deserves all the credit for stopping them; but throughout the battles, Cowan's ships and a French flotilla provided artillery support and transport, enabling Latvian forces to capture the fortress of Daugavgriva and turn the enemy flank. In the process, HMS Dragon was struck by German artillery with the loss of nine lives. Soon after, Avalov's forces attacked Liepaja, and again the Allied ships acted as floating batteries, covering the Latvian counter-attack that drove the Germans out of the city.

HMS Dragon in action

HMS Dragon in action

The Bolsheviks decided to make peace with Estonia and thus exclude it from among the enemies of Soviet Russia. In August Moscow officially offered peace to Estonia. The Estonian politicians and the higher military were divided in two on this matter, trying to work out whose victory in the Russian Civil War (Whites or Reds) would be more advantageous for Estonia. The majority thought that the Whites, who were reluctant to recognised Estonian independence, constituted a bigger threat. In autumn 1919 it was realised that the Russian Whites were going to lose, so the only chance of getting the economically struggling Estonia out of the gruelling war was to make peace with the Bolsheviks. Another factor supporting this decision was that throughout 1919 the Republic of Estonia had failed to get de jure recognition from the Western countries.

Signing the Tartu Peace Treaty

Signing the Tartu Peace Treaty

Peace talks with Soviet Russia started on 5 December 1919 in Tartu. The simultaneous offensive of the Red Army aiming to influence the talks did not produce the desired effect. An armistice was announced on 3 January 1920. On 2 February the Tartu Peace Treaty was signed – the Republic of Estonia and the Soviet Russia recognised each other, declared the end of the war and determined the post-war cooperation plans. The War of Independence had cost the Estonian troops about 2,300 men killed, about 13,800 were wounded (including about 300 killed and 800 wounded in the Landeswehr War), plus the losses of foreign volunteers and allied forces.

Next: Finnish Volunteer Units in Estonia: Pohjan Pojat ("Sons of the North") and I Suomalainen Vapaajoukko (Ist Finnish Volunteer Corps) – and the Ingrian Uprising