The Australia-Finland Assistance Organisation

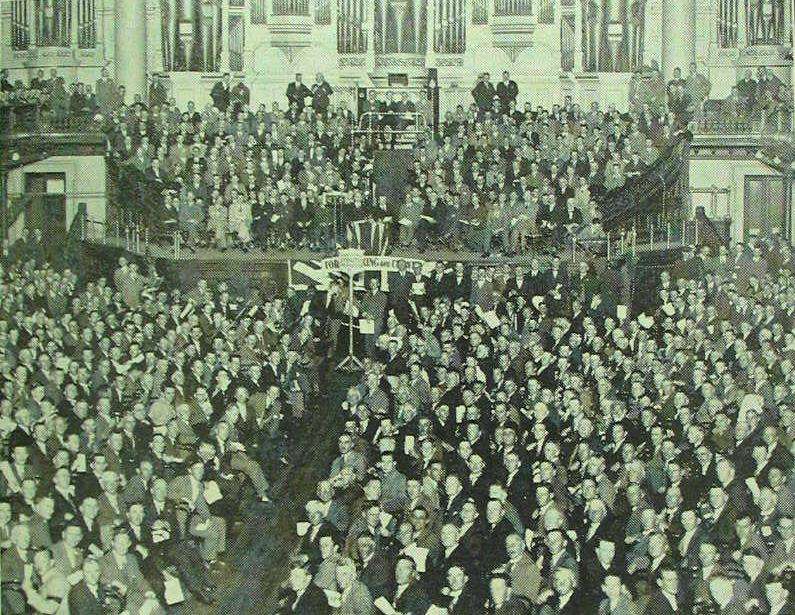

On the 30th of November, 1939, the Soviet Union attacked Finland with no declaration of war. The Valtioneuvoston Tiedotuskeskus team in Sydney had been warned that this was probable and was well prepared, with contacts in the Australian news media by now well established and background information prepared. Immediately the Soviet attacks commenced, telegrams to Valtioneuvoston Tiedotuskeskus teams around the world were dispatched, instructing them to initiate the plans that had been prepared for this eventuality. Short of any news on the Phony War, the Australian news media splashed the new of the Soviet attack on Finland across the front pages. Along with the front page headlines were a continuous stream of background articles filling the newspapers, describing Finland, setting out the situation, providing a background to the unprovoked attack on a small neutral country which wished only to remain at peace, suggesting ways in which Australians could assist Finland. The immediate Australian public reaction was one of indignation and condemnation of the USSR’s actions. Editorials stridently critical of the USSR blazed across every newspaper in the country. Well-prepared and prominent supporters of Finland spoke on the radio and seemingly overnight, the Australian Finland Assistance Organisation emerged, announced on the 3rd of December 1939 at a packed public meeting in Sydney where the prominent speakers included the joint founders (whom we will cover in the next Post), Dr Lewis Windermere Nott and Colonel Eric Campbell together with the Rev. Kalervo Kurkiala.

Image sourced from: http://matthewleecunningham.files.wordp ... p-1931.jpg

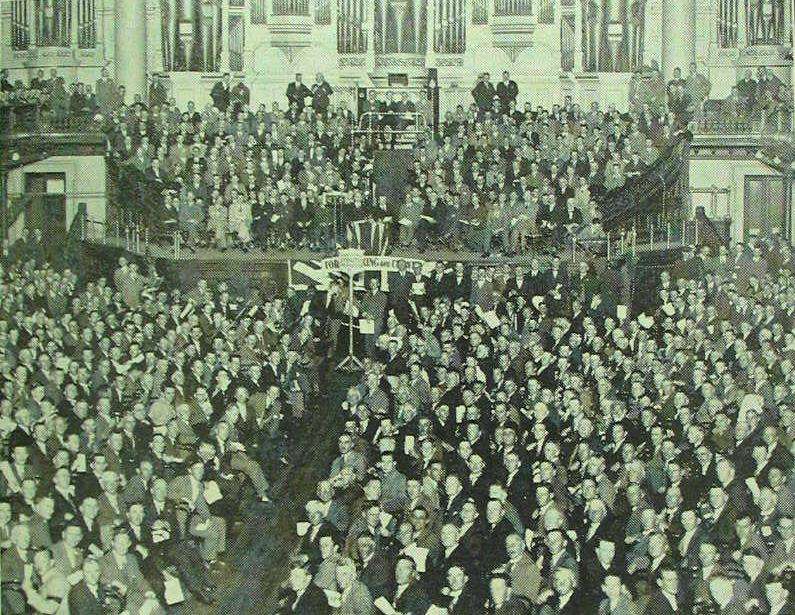

The inaugural meeting of the Australian Finland Assistance Organization in Sydney on the 3rd of December 1939 was packed to capacity.

Image sourced from: http://matthewleecunningham.files.wordp ... p-1931.jpg

The inaugural meeting of the Australian Finland Assistance Organization in Sydney on the 3rd of December 1939 was packed to capacity.

Dr Lewis Windermere Nott and Colonel Eric Campbell had laid the foundations for the Australia-Finland Assistance Organisation well. The day that the war broke out, letters and telegrams began to pour out of the Sydney Office asking those who had indicated their willingness to help to start work immediately whilst newspaper articles nationwide reported the founding of the Organisation and provided contact details for those who wished to setup branches or to join. Within days, branches of the Australian Finland Assistance Organization had been established across Australia, with offices prominently positioned in main streets. Churches, factories, schools, Returned Sailors and Soldiers Imperial League of Australia Halls, the Australian Country Women’s Association, the Australian Red Cross, all were pressed into service as popular enthusiasm led to the organisation’s membership soaring into the thousands within days and into the tens of thousands within a fortnight. Fund-raising activities commenced almost immediately, with Churchs taking up Collections for Finland, street corner collectors in the cities and large towns, collections in the factory and the office, fund-raising fetes and, on a larger scale, requests to businesses for donations. Within days, thousands of pounds had been collected, within weeks, tens of thousands as the Australian public responded to the call. By mid-December 1939, it seemed that a large percentage of the Australian population were involved in the campaign to support Finland. It was a cause that stirred enthusiasm in the public, far more so than the war with Germany. And this enthusiasm was in large part the result of the skilful and ongoing distribution of information, news articles and commentary provided by the Valtioneuvoston Tiedotuskeskus team.

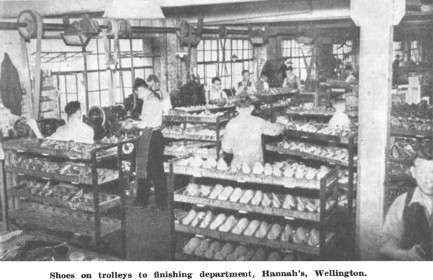

Image sourced from: http://www.officemuseum.com/1932_Clerks ... ngland.jpg

The Head Office of the Australian Finland Assistance Organization was staffed by Volunteers and was a large and meticulously organized hive of industry. The Sydney Finnish community played a large part in the initial establishment of the Office but were soon joined by hundreds of Australian volunteers eager to help the cause of Finland as the Australia-Finland Assistance Organisation rapidly became an “Australia-wide” organization. The small Finnish community would continue to play a strong supportive role in the Organisation in Sydney, working in the Organisation’s Head Office performing the mundane administrative work that any such Organisation needs carried out efficiently in order to be successful.

Image sourced from: http://www.officemuseum.com/1932_Clerks ... ngland.jpg

The Head Office of the Australian Finland Assistance Organization was staffed by Volunteers and was a large and meticulously organized hive of industry. The Sydney Finnish community played a large part in the initial establishment of the Office but were soon joined by hundreds of Australian volunteers eager to help the cause of Finland as the Australia-Finland Assistance Organisation rapidly became an “Australia-wide” organization. The small Finnish community would continue to play a strong supportive role in the Organisation in Sydney, working in the Organisation’s Head Office performing the mundane administrative work that any such Organisation needs carried out efficiently in order to be successful.

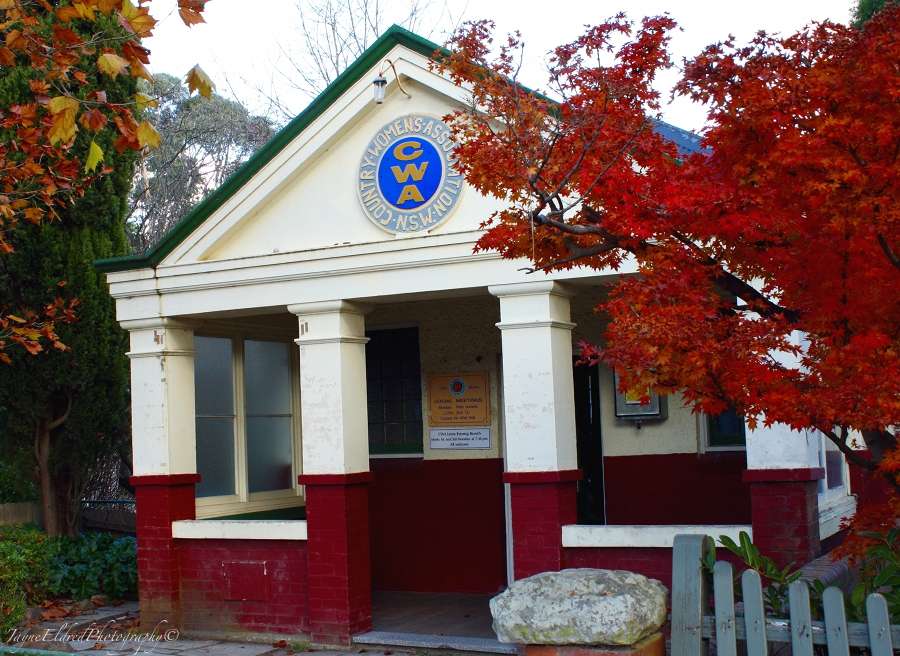

Two Australian organizations were perhaps the most instrumental in the rapid expansion of support for the Australia-Finland Assistance Organization. These were the Returned Sailors and Soldiers Imperial League of Australia and the Country Women’s Association of Australia, both large and well-organised groups with memberships of well over one hundred thousand and with branches in every city, town and small rural farming community in Australia. Both were also fairly conservative patriotic organizations in all the best senses of the words.

Image sourced from: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/c ... _Wagga.jpg

RSL sub-branch club-rooms in Wagga-Wagga: The Returned Sailors and Soldiers Imperial League of Australia was founded in 1916 and had originally been established out of concern for the welfare of soldiers who had served in the military in WW1. As well as arguing for veterans' benefits, it entered other areas of political debate and was very much politically conservative, with members supporting the British Empire and the King. In most areas of Australia, sub-branches of the League established clubrooms where war veterans could meet and socialise with their old comrades, with the land for the club buildings often donated by the various State governments. The Clubs were generally run on commercial principles and served alcohol and food. They were highly popular with veterans of WW1. From 1938 on, the RSL began to operate retirement homes for the care of aged veterans. Many RSL members, particularly those who had been officers, had also been members of the New Guard and as such, Colonel Campbell was able to recruit the support of RSL branches and sub-branches across Australia to the support of the Australia-Finland Assistance Organisation.

Image sourced from: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/c ... _Wagga.jpg

RSL sub-branch club-rooms in Wagga-Wagga: The Returned Sailors and Soldiers Imperial League of Australia was founded in 1916 and had originally been established out of concern for the welfare of soldiers who had served in the military in WW1. As well as arguing for veterans' benefits, it entered other areas of political debate and was very much politically conservative, with members supporting the British Empire and the King. In most areas of Australia, sub-branches of the League established clubrooms where war veterans could meet and socialise with their old comrades, with the land for the club buildings often donated by the various State governments. The Clubs were generally run on commercial principles and served alcohol and food. They were highly popular with veterans of WW1. From 1938 on, the RSL began to operate retirement homes for the care of aged veterans. Many RSL members, particularly those who had been officers, had also been members of the New Guard and as such, Colonel Campbell was able to recruit the support of RSL branches and sub-branches across Australia to the support of the Australia-Finland Assistance Organisation.

In working to gain the support of the RSL, Valtioneuvoston Tiedotuskeskus would constantly highlight that Finns and Finnish-Australians had fought and died for Australia in WW1 out of selfless patriotism and loyalty to their adopted country. And now, when Finland was in need, Finnish Australians were rallying to support their old homeland, and asking for the support of all Australians to help their country remain free from Soviet tyranny – and the Soviet Union was the ally and friend of Nazi Germany, with whom Australia was officially at war. Stalin and Hitler were described as but two faces of the same totalitarian enemy whom free peoples around the world were fighting. Much was also made of the way in which Germany under Hitler and the USSR under Stalin had jointly attacked Poland – and now, while Germany attacked Britain, the USSR was attacking Finland. As a returned Finnish-Australian WW1 veteran, Niilo Kara would find himself speaking at fund-raising events throughout New South Wales in support of Finland.

Pihlajaveteläinen Niilo Kara osallistui vapaaehtoisena ensimmäiseen maailmansotaan Australian joukoissa haavoittuen rintamalla. Toivuttuaan hän palasi Australiaan ja toimi jonkin aikaa farmarina. Kuva Siirtolaisinstituutti, Turku / Niilo Kara fought in the First World War as a volunteer in the Australian Army, where he was wounded at the front. After recovering, he returned to Australia and was for some time a station hand (a “station” in the Aussie and Kiwi vernacular is a very large sheep or cattle farm). Picture from the Migration Institute, Turku, Finland

Pihlajaveteläinen Niilo Kara osallistui vapaaehtoisena ensimmäiseen maailmansotaan Australian joukoissa haavoittuen rintamalla. Toivuttuaan hän palasi Australiaan ja toimi jonkin aikaa farmarina. Kuva Siirtolaisinstituutti, Turku / Niilo Kara fought in the First World War as a volunteer in the Australian Army, where he was wounded at the front. After recovering, he returned to Australia and was for some time a station hand (a “station” in the Aussie and Kiwi vernacular is a very large sheep or cattle farm). Picture from the Migration Institute, Turku, Finland

Image sourced from: http://farm4.staticflickr.com/3013/3524 ... fe2a_o.jpg

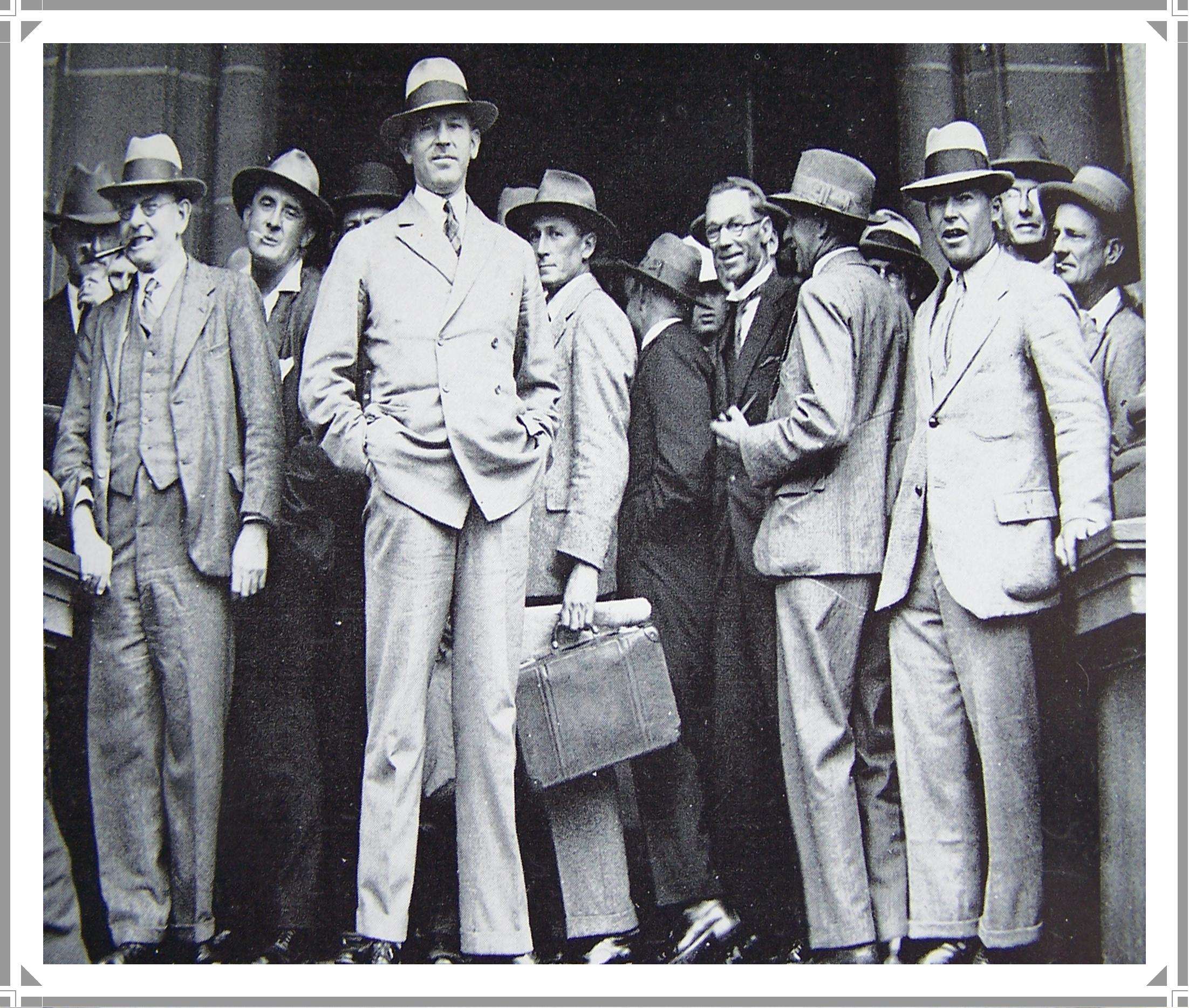

A rural Australian CWA branch: The Australian Country Women’s Association was in some ways the female equivalent of the RSL but was formed out of rather more desperate needs than the desire to socialize and support one’s old WW1 comrades. Rural Australian in the early 1920’s was a large area, and rural women often lived lives of isolation, with an appalling lack of health facilities. The Country Women's Association was formed in both New South Wales and Queensland in 1922 by women who had to watch helplessly as their children died from minor illnesses. These women realised they had nowhere to turn but to themselves - and the result was staggering. Within a year, the Association was a unified, resourceful group that was going from strength to strength. The members worked tirelessly to set up baby health care centres, fund “bush nurses”, build and staff maternity wards, hospitals, schools, rest homes, seaside and mountain holiday cottages - and much more. At the same time they continued to run homes in which they were often mother, nurse, teacher and general hand. The women of the CWA, while believing deeply that their role in the family was vitally important, provided social activities and educational, recreational and medical facilities. The CWA expanded into South Australia in 1929 and by 1936 there was a branch in each of the States and Territories of Australia. During the depression years, the CWA helped those in need with food and clothing parcels. In the late 1930’s, as now, it was the largest women’s organisation in Australia.

Image sourced from: http://farm4.staticflickr.com/3013/3524 ... fe2a_o.jpg

A rural Australian CWA branch: The Australian Country Women’s Association was in some ways the female equivalent of the RSL but was formed out of rather more desperate needs than the desire to socialize and support one’s old WW1 comrades. Rural Australian in the early 1920’s was a large area, and rural women often lived lives of isolation, with an appalling lack of health facilities. The Country Women's Association was formed in both New South Wales and Queensland in 1922 by women who had to watch helplessly as their children died from minor illnesses. These women realised they had nowhere to turn but to themselves - and the result was staggering. Within a year, the Association was a unified, resourceful group that was going from strength to strength. The members worked tirelessly to set up baby health care centres, fund “bush nurses”, build and staff maternity wards, hospitals, schools, rest homes, seaside and mountain holiday cottages - and much more. At the same time they continued to run homes in which they were often mother, nurse, teacher and general hand. The women of the CWA, while believing deeply that their role in the family was vitally important, provided social activities and educational, recreational and medical facilities. The CWA expanded into South Australia in 1929 and by 1936 there was a branch in each of the States and Territories of Australia. During the depression years, the CWA helped those in need with food and clothing parcels. In the late 1930’s, as now, it was the largest women’s organisation in Australia.

While Australian newspapers wrote in glowing terms of Finnish bravery as Finland defended itself against the attacker from the East, Australian Finns worked to support their Fatherland. Much had been made in the Australian newspapers of the Lotta Svärd organization and how they supported the Army and the war effort in Finland. In Sydney, Miss Aino Potinkaraa publicly opened a Sydney branch of the Lotta Svärd on the 4th of December and in an interview with the Sydney Morning Herald, spoke about the 30 Finnish women who met every night to knit woollen clothes for the Finnish soldiers and Finnish children. The news article sparked off a flood of inquiries about establishing similar clubs which were responded to quickly, the net result being similar groups under the aegis of the Australian Country Women’s Association being established across Australia, with the results that we have seen in an earlier post. Within days, Miss Aino Potinkaraa found herself the very public figurehead of the Australian Lotta Svärd, travelling around Australia making speeches at CWA branches, in Churches and at Schools, advising as to how women and schoolchildren could help Finland.

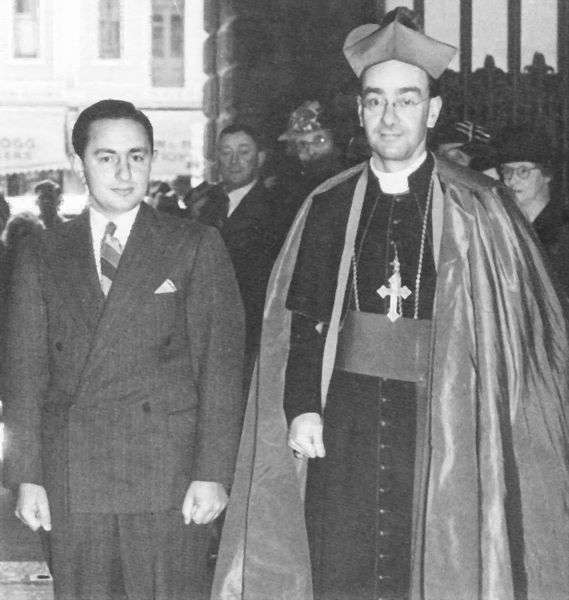

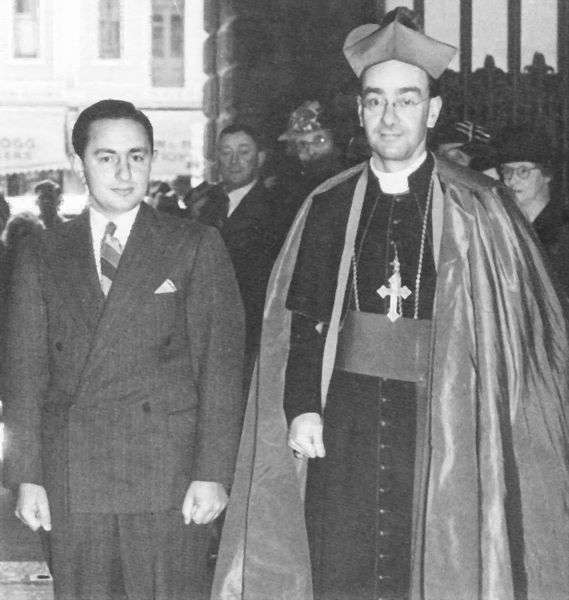

Similarly, the Rev. Kalervo Kurkiala, as a Lutheran minister, would speak at both Protestant and Catholic Churches throughout Queensland, New South Wales and Victoria. The Australian Catholic Church was large (in pre-WW2 Australia, Irish Catholics and the descendants of Irish Catholics made up a significant part of the country’s population), influential and was stridently anti-Communist, with the Spanish Civil War having magnified Australian Catholic fears that the Communist menace would spread across Europe. The Soviet attack on Finland served only as an illustration that these fears were well-founded, albeit Finland was a Lutheran Protestant country rather than a Catholic country. Still, this made little difference to Australian Catholics and the Catholic Church were firmly and whole-heartedly supportive of Finland and of the Australia-Finland Assistance Organisation. The Australian Catholic Church would also throw their political weight behind the increasingly vocal campaign to send Australian volunteers to Finland. A widely circulated newspaper, the “Catholic Worker”, edited by Bartholomew Augustine Santamaria, played a prominent part in Catholic support for Finland.

Image sourced from: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/c ... a_1943.jpg

Catholic Archbishop of Adelaide Matthew Beovich with B. A. Santamaria at the first Catholic Action Youth rally in support of Finland, mid-December 1939. Archbishop Daniel Mannix, the acknowledged leader of the Australian-Irish community, was also a close friend and supporter of Santamaria’s.

Image sourced from: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/c ... a_1943.jpg

Catholic Archbishop of Adelaide Matthew Beovich with B. A. Santamaria at the first Catholic Action Youth rally in support of Finland, mid-December 1939. Archbishop Daniel Mannix, the acknowledged leader of the Australian-Irish community, was also a close friend and supporter of Santamaria’s.

Bartholomew Augustine Santamaria (14 August 1915 - 25 February 1998), known as Bob Santamaria, was an Australian political activist and journalist. A highly divisive figure, with strongly held anti-Communist views, Santamaria inspired great devotion from his followers and intense hatred from his enemies. Santamaria was a political activist from an early age, becoming a leading Catholic student activist and speaking in support of Franco's forces in the Spanish Civil War. He also was a strong supporter and wrote about Mussolini's regime in Italy, but denied that he had ever been a supporter of fascism. He always disliked and opposed Hitler and Nazism. He attributed Mussolini's alliance with Hitler to the failed policies of Anthony Eden and expressed regret that Mussolini aligned himself with Hitler. In 1936 Santamaria was one of the founders of the Catholic Worker newspaper and was the first editor of the paper which declared itself opposed to both Communism and Capitalism. In 1937, at the invitation of Archbishop Daniel Mannix, he joined the National Secretariat of Catholic Action, a lay Catholic organisation. Santamaria was also close to many influential Catholic Labour Party politicians, including Arthur Calwell and James Scullin (who would go on to become Labour Party Prime Minister). Bob Santamaria would strongly support the work of the Australia-Finland Assistance Organisation and would be a leading member and speaker for the Organisation throughout the Winter War and for that matter, through WW2.

During WW2he would found the Catholic Social Studies Movement, which recruited Catholic activists to oppose the spread of Communism, particularly in the trade unions. The movement gained control of many unions and brought him into conflict with many left-wing Labor Party members, who favoured a united front with the Communists during the war. During the 1930s and 1940s Santamaria generally supported the conservative Catholic wing of the Labor Party, but as the Cold War developed after 1945 his anti-Communism drove him further away from Labor. In 1954 H V Evatt, leader of the Labour Party, publicly blamed Santamaria for Labor's defeat in that year's federal election, and his parliamentary followers were expelled from the Labor Party. The resulting split brought down the Labor government in Victoria. During the 1960s and 1970s Santamaria regularly warned of the dangers of communism in Southeast Asia, and supported the United States in the Vietnam War.His political role gradually declined. But his personal stature continued to grow through his regular column in The Australian newspaper and his regular television spot, Point of View (he was given free air time by Sir Frank Packer, owner of the Nine Network). A skilled journalist and broadcaster, he was one of the most articulate voices of Australian conservatism for more than 20 years and was greatly admired by conservative politicians. Santamaria had the satisfaction of living to see the fall of the Soviet Union.

Many fund-raising events took place through December 1939 and January 1940. One of the more notables was a series of concerts organized by the Sydney Symphony Orchestra in conjunction with the Australian Broadcasting Company. The guest conductor was Georg Schnéevoigt (8 November 1872 – 28 November 1947), a Finnish musician and conductor who was also a close friend of the great Finnish composer Jean Sibelius. The first concert of the series was graced by the presence of the Governor of NSW, John de Vere Loder, 2nd Baronet Wakehurst and his wife. The program began with the playing of Finland's national anthem, followed by Sibelius' Symphony No. 1 E Minor, Opus 39 and after the interval, the Karelian Rhapsody, Palmgren’s "Pastorale" and Sibelius's Suite "Walse Triste" and finally, Finlandia.

Image sourced from: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/c ... evoigt.jpg

Guest Conductor Georg Schnéevoigt, a close friend of the great Finnish composer Jean Sibelius.

Image sourced from: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/c ... evoigt.jpg

Guest Conductor Georg Schnéevoigt, a close friend of the great Finnish composer Jean Sibelius.

The wife of the Finnish Consul, Mrs. Simelius, also took on a public role with the organization, herself managing the group within Head Office that organized the collection of clothing donations from the Australian people. The volume of clothing collected in this way was large, and the logistical management task was substantial, with large volumes of winter clothing collected or made by volunteers of the CWA being transported by the Australian railways from all around Australia to warehouses in Melbourne from where large groups of volunteers further assisted in sorting and packing for shipment. In addition to funds collected by local branches of the Australia-Finland Asssistance Organisation, donations also poured in to the Head Office in Sydney, with hundreds, and then thousands, of letters arriving daily. All had to be opened, read, donations collected and replies written and posted. Perhaps fortunately, the Australian Post Office, on the instructions of the Postmaster-General, provided postage free of charge to the organization for both incoming and outgoing mail.

Examples included a lady who wrote to the Sydney Morning Herald urging donations to the Organisation’s funds and as an example to others, she sent in £200 to help Finland. A Sydney suburban school sent a letter that read in part: "

We're just little kids, and we do not have a lot of money, but we hope that the 10 shillings we have sent will help to buy bandages for small Finnish children who have been injured.” At the same time, the Australian Government announced it was donating £10 000 to the Finnish Red Cross as a starting point and would match all privately donated monies sent in to the Organisation. The administration of the Australia-Finland Asssistance Organisation’s accounts were entrusted to Sir John Peden, a noted Barrister, Professor of Law and President of the NSW Legislative Council (the Upper House of the New South Wales Parliament, the President of which was the equivalent of the Speaker in the Lower House) from 1929 to 1946 as well as to Lady Kater (appointed as Secretary) and Mr. R. S. Maynard, Treasurer. In all, the Australian-Finland Assistance Organisation raised funds of slightly more than £1,400,000 (more than 200,000,000 Finnish marks) from public donations. This was of course in addition to donations in kind of food, clothing and the numerous bales of war wool which Australian farmers donated and was matched by the Australian Government. It was a magnificent fund-raising effort for a small country as far removed from Finland as it was possible to be.

Australian Politics and the dispatch of the Australian Volunteers

In Australia, as elsewhere, public opinion had been aroused by the appeal of the Finnish government to the League of Nations for assistance against Soviet aggression, and the subsequent resolution of the Assembly which called upon every member to furnish Finland with all possible material and humanitarian assistance. Typical of the Australian public response was that of a woman in Sydney who signed her letter on December 6th 1939 to the daily newspaper, the Sydney Morning Herald, as “Woman Sympathiser.” She wrote that she had been waiting in vain for some public figure in the Government in Australia to take the lead in standing beside New Zealand in sending help to the heroic Finns. Recognising that it was hard for Australians, in their isolation and with their deep rooted sense of security, to visualize the epic struggle, the woman argued that the Finns were fighting not only for their homes and liberties but for Australia’s as well. Her letter garnered much support and many supporters wrote in a similar vein. Despite this support, the Menzies Government remained non-committal. The Government’s military advisors did not think that the Finnish Army could hold out against the might of the Red Army and advised the Government that the war would be over before any Volunteers from Australia could reach Finland.

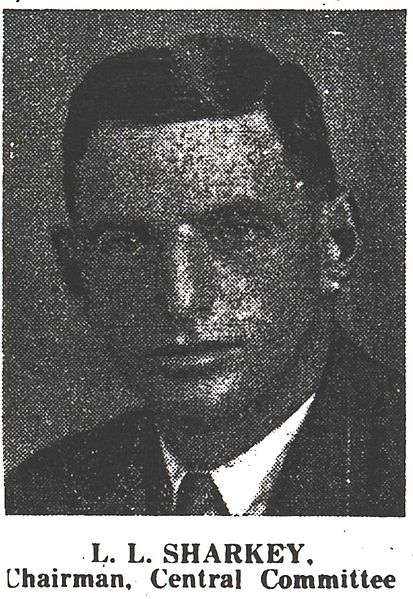

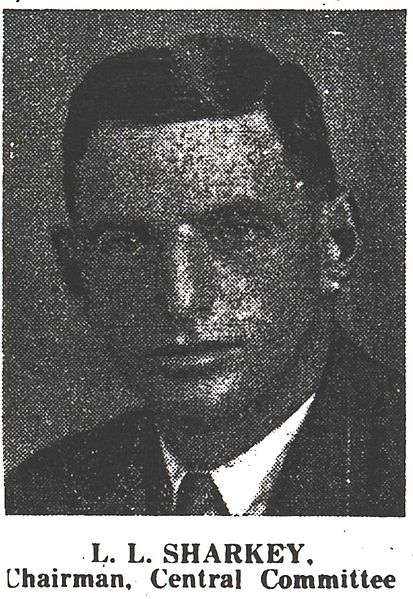

However, the news reports from Finland on the fight the Finnish Army was putting up, the large casualties being inflicted on the invading Russians, the early Finnish victories, all fed a demand to send volunteers that was carefully and discretely fanned by the Valtioneuvoston Tiedotuskeskus team. And it wasn’t hard to fan - opinion from the countryside and from the influential Returned Servicemens :eagure was best illustrated by the vitriolic abuse hurled at the Soviet Union by the weekly Bulletin, where the bush ethos and the radical tradition were still served by the pen of Norman Lindsay. The Catholic Worker, edited by Bob Santamaria, we perhaps not as vitriolic but was certainly equally strident in it’s call for the dispatch of Volunteers. Within the pages of the media, there was little opposition to the calls to support Finland. The main opposition to these calls would come only from the small Communist Party of Australia and its leader, Lance Sharkey.

Image sourced from: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/e ... 30s%29.jpg

Lawrence Louis "Lance" Sharkey (1898 – 1967) joined the Communist Party in 1924 and emerged in 1928 as a strong advocate of the Comintern line when he was elected to the CPA's governing Central Committee. In 1929 he was appointed editor of the party newspaper “Workers' Weekly” and would edit that paper and another party publication, “The Tribune”, through the 1930s. He became Chairman of the CPA in 1930 and would hold the post until 1948 (from 1948 to 1965 he served as the Secretary-General of the Party - closely following the prevailing Soviet line in each major turn of policy). In the summer of 1930 Sharkey visited the Soviet Union for the first time.When Prime Minister Sir Robert Menzies declared the CPA illegal in June 1940, Sharkey and other party leaders went underground. A year later when Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union, the ban on members of the CPA was relaxed and Sharkey resumed open political activity. In March 1949 Sharkey told a Sydney journalist that "if Soviet Forces in pursuit of aggressors entered Australia, Australian workers would welcome them." For this statement Sharkey was tried and convicted of sedition. The High Court upheld his conviction; and in October he was sentenced to three years' imprisonment. He remained prominent in the Australian Communist Party where he minimised Khrushchev's repudiation of Stalin in 1956 and the Soviet invasion of Hungary later that year. He died of a heart attack on 13 May 1967 in Sydney.

Image sourced from: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/e ... 30s%29.jpg

Lawrence Louis "Lance" Sharkey (1898 – 1967) joined the Communist Party in 1924 and emerged in 1928 as a strong advocate of the Comintern line when he was elected to the CPA's governing Central Committee. In 1929 he was appointed editor of the party newspaper “Workers' Weekly” and would edit that paper and another party publication, “The Tribune”, through the 1930s. He became Chairman of the CPA in 1930 and would hold the post until 1948 (from 1948 to 1965 he served as the Secretary-General of the Party - closely following the prevailing Soviet line in each major turn of policy). In the summer of 1930 Sharkey visited the Soviet Union for the first time.When Prime Minister Sir Robert Menzies declared the CPA illegal in June 1940, Sharkey and other party leaders went underground. A year later when Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union, the ban on members of the CPA was relaxed and Sharkey resumed open political activity. In March 1949 Sharkey told a Sydney journalist that "if Soviet Forces in pursuit of aggressors entered Australia, Australian workers would welcome them." For this statement Sharkey was tried and convicted of sedition. The High Court upheld his conviction; and in October he was sentenced to three years' imprisonment. He remained prominent in the Australian Communist Party where he minimised Khrushchev's repudiation of Stalin in 1956 and the Soviet invasion of Hungary later that year. He died of a heart attack on 13 May 1967 in Sydney.

In January 1940 Sharkey explained the facts as Australian communists saw them. Finland had been ruled by Mannerheim’s clique for twenty years. The clique had come to power at the point of the bayonets of German imperialism which had overthrown the socialist government that the workers had established in Finland during the course of the Russian revolution, murdering between 30,000 and 50,000 Finnish and Russian workers in the process. Australian communists were told that Mannerheim had established a White Terror Dictatorship in which the Communist Party was suppressed and trade union recognition was illegal until the last hours before the War. The government of Kuusinen was, by this account, the legitimate successor to the government of the Finnish People which had been overthrown by the bayonets of Mannerheim and Von Der Goltz in 1920. Sharkey argued that the Finnish White Guards were the mortal enemies of the Soviet Union and stressed that Finnish Reaction was dangerous because it was a puppet of world imperialism, a dagger in the hands of British, French and German imperialism. It was a danger because the Finnish terrain, in the hands of a strong Army, would make it a most powerful military base, especially as Finland commanded the approaches to Leningrad and Murmansk. The Finnish White Guards, added Sharkey, could have had a treaty with the Soviet Union on the same terms as the three Baltic States. This they had refused, believing in the support of British and French imperialism and, behaving provocatively, even firing on Soviet troops. Sharkey concluded by describing the Finnish negotiations with the Soviet Union as sabotage. But he was glad to report that the mutual assistance treaty between Kuusuninen’s Finnish Government and the Soviet Union made Finland and the Soviet Union secure from attack (noting in passing that the capitalist rulers of Finland are of Swedish extraction), and he comprehensively predicted that the toiling people of the whole world would rejoice at the liberalization of their brothers in Finland, and would spit on the lies of capitalism, the millionaire press, the labour imperialists and the Trotskyite hirelings. That this of course did not fly with the Australian public is more or less needless to state. The only believers were the credulous supporters of the official Communist Party line and these were few and far between.

In Australia, the question of raising Volunteers to fight in Finland unsurprisingly received a great deal of public support. The substantial and nation-wide network of voluntary organizations that had sprung up to raise money and collect aid for Finland had, as it had in many other countries also, taken on a life of it’s own. The news media fed the public mood with continued stories of the heroic fight being put up by the Finns and the stories of the early volunteers (and in Australia and New Zealand in particular, the rapid dispatch in late December 1939 to the frontlines of the ANZAC Volunteer Battalion). The news that New Zealand, Australia’s minuscule neighbour in the South Pacific, was planning to dispatch a second volunteer Battalion to Finland acted like bait to a Great White Shark as far as Australian public opinion was concerned. The debate grew heated, the editorial pages in the Australian newspapers castigated the Australian government for a lack of support for a small fellow-democracy fighting for its life and used the dispatch of TWO volunteer battalions from tiny New Zealand as a whip with which to lash the Menzies Government – whom they were already criticizing for not dispatching troops of the Australian Imperial Force to Europe to fight with the British Army in a timely manner.

It is idle to suppose that government in Australia took no notice of public comment. Response to public opinion was a cornerstone of the Westminister style of government, and the Menzies administration took criticism seriously enough to look at the Winter War in Cabinet. H.S. Gullet briefed the Cabinet on facts and information necessary for them to deliberate on the question of aid for Finland. The obvious vital issue was whether aid to Finland should be confined to humanitarian assistance or whether Australia should also offer military assistance. The first ction taken, on the 10th of December, was that in light of the strong Australian support for Finland, the Government would match all private donations made to the Australian-Finland Assistance Organisation on a one for one basis. Cabinet was also advised that the Finnish Government had been advised that all orders placed for the purchase of non-armament related items would be approved without hesitation. It was spelled out in some detail to the Cabinet as to what these orders consisted of and that these did not threaten in any way the ability of Australia to support the war against Germany. This information was passed in code to the Australian High Commissioner in London, who was instructed to inform the United Kingdom Government and the Finnish Government. Gullett also recommended to the Cabinet that they send the League of Nations a telegram stating that Australia was fully in accord with the resolution expelling the Soviet Union from the League, and was prepared to offer Finland such assistance as was practicable. The Cabinet also approved these actions.

Once the decision to permit fund raising, donations and the selling of goods to support the Finnish war effort was approved, the Australia-Finland Assistance Organisation and their supporters began to press their claims harder. The pressure came from two distinct quarters: from medical practitioners who wished to man field hospitals in Finland, and from Australians who wished to fight there. Dr Lewis W. Nott, a medical practitioner, former member of the House of Representatives and one of the founders of the Australia-Finland Assistance Organisation was foremost among those trying to organize a Field Hospital and medical units for the Winter War. He wrote a series of letters to the Prime Minister and to the daily press in which he pointed out that in Britain organized recruiting was going on for military as well as medical aid for stricken Finland. Following the governments substantial commitment to Finnish Aid, Nott asked whether the Prime Minister would give his imprimatur to the ambulance and medical units and field hospital that Nott was organizing. There were, Nott said, many professional men like himself, who though medically fit, and with excellent civil and military records, were not allowed to go overseas with the second A.I.F. (Australian Imperial Force).

Following his first article in a Sydney newspaper offering to organize the field hospital, medical and ambulance units, Nott was inundated by an overwhelming response from surgeons, specialists, dentists and nurses from all states, even as far afield as North Queensland, South Australia and Western Australia. In a further article the following day, Dr. Nott pointed out that Australia’s fate was inextricably bound up with that of Finland, and Finland’s “Gallant Resistance” was an inspiration to democracy at its intelligent best. There was, Nott repeated, not one obstacle in the path of staffing the Unit at once, but the question of transport, stores and upkeep was the major consideration. Nott could only visualize the unit succeeding by a combination of government and voluntary assistance. Even as Dr. Nott led the campaign, the Australia-Finland Assistance Organisation, with the assistance of retired, reservist and militia officers, put together the proposed medical units and assessed and signed up Volunteers to serve in them should approval be given.

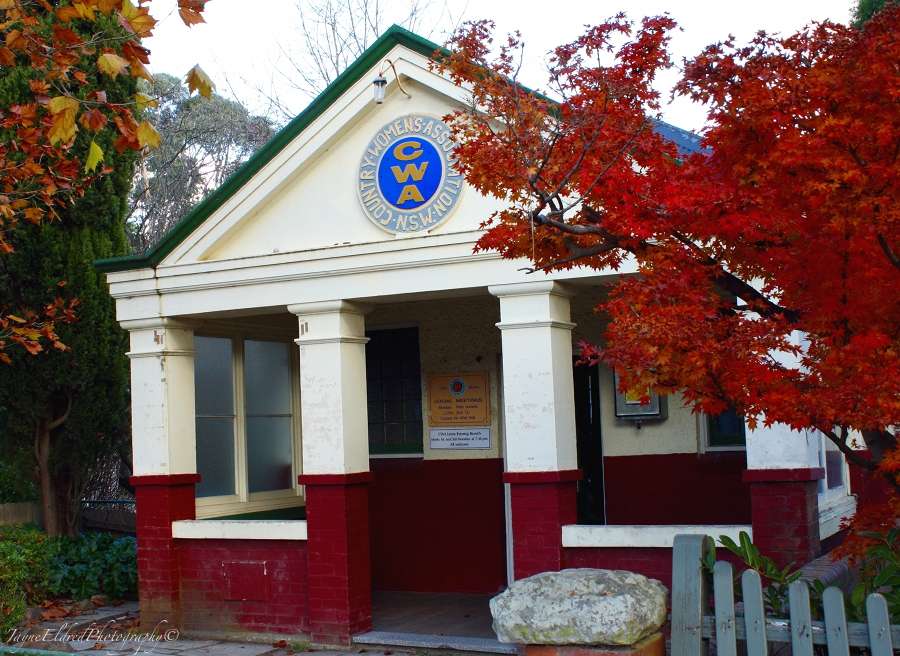

A parallel campaign was also underway supporting the dispatch of a Volunteer contingent to Finland. This aspect of the campaign was spearheaded on the one hand by Colonel Campbell, and on the other by a Mr. Charles C. K. Foot, of Western Australia. The point was made that the crucial test of Australian intentions in the fight against totalitarianism in all its guises was the issue of whether Australian volunteers would be permitted to go to Finland to fight. Traditionally Australians had been quick to volunteer and there was a long tradition also in effect by which all service overseas was voluntary. Australian volunteers had been among the first to fight in the Boer War in South Africa at the end of the nineteenth century. In 1914 they enlisted in droves to volunteer for overseas service. The view that men needed to be conscripted for overseas military service split the nation as the First World War dragged on, and there was a hard dying tradition that the need would find the men. Therefore it was hardly surprising that Australians should volunteer by the thousand to fight in Finland – and the Australian newspapers continually pointed out that hundreds of men every day were writing or visiting the Assistance Organisation’s offices and signing up as Volunteers to fight.

Colonel Campbell and Charles Foot pleaded their cause, with the at times strident support of every newspaper in Australia. Even the Labour Party opposition joined the chorus, perhaps influenced by their large Irish Catholic constituency and the support of such articulate activists as Bob Santamaria. The War Cabinet first debated the issue at its meeting in Melbourne on 20 December 1939. Gullet introduced the agenda item with a brief sketch of Finlands appeal to the League of Nations, and the Leagues request for clarification of the Australian Governments intentions. Gullets information was that while the United Kingdoms reply to the Secretary General of the League merely stated that it would give “such assistance as was practicable”, the government was assisting materially with the provision of aircraft, anti-aircraft and artillery guns and ammunition. Further, Gullett had been informed that the United Kingdom was already in the process of considering the dispatch of Volunteers and that the UK and France had also jointly made proposals to both Norway and Sweden that, in the event of their rendering every possible assistance to Finland and as a consequence themselves becoming involved in hostilities, Great Britain would be prepared to consider what assistance it could give to these countries.

The Cabinet further considered the sending of volunteers on the next day. H. S. Gullett pointed out the legal difficulties. The British Foreign Enlistment Act of 1870 made it unlawful for a British subject to enlist in the military or naval service of a foreign country which was at war with a state at peace with His Britannic Majesty. This Act applied to Australia, and had been invoked at the time of the Spanish Civil War to prevent Australians from leaving the country to join the International Brigades. There was however, Gullett admitted, provision in the 1870 Act for the King to grant a license which would permit British subjects to enlist and help Finland. Gullett recommended however that no action be taken over Australian Volunteers for Finland. He pointed out that apart from the obvious practical difficulties and the need for concentration on the official Australian war effort. He also stated that it was doubtful whether any effective assistance to Finland could be provided as it would be months before volunteers from Australia could have received adequate training and reached Finland, and by that time the question of Finlands ability to resist Russian aggression would in all likelihood have been decided. On the information Gullett had at that time it appeared that unless Finland received Allied help on a substantial scale in the near future she would be compelled to sue for peace. If the Allies decided that they were not in a position to give such help, the sending of Australian volunteers would serve no useful purpose. The Cabinet agreed with Gullett to postpone a decision on the matter and further consider it in the New Year.

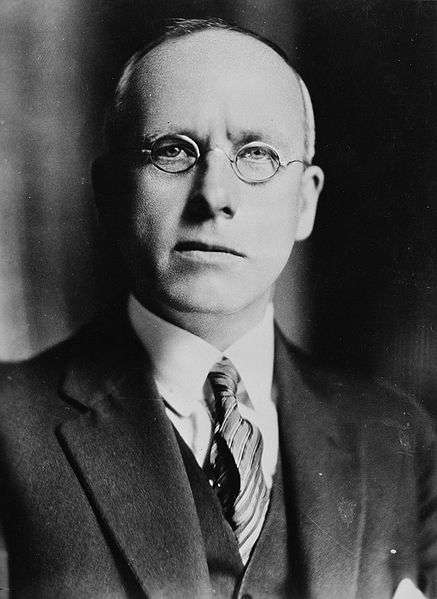

Image sourced from: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/c ... ullett.jpg

Sir Henry Somer Gullett KCMG (26 March 1878 – 13 August 1940) was an Australian Cabinet Minister and member of the House of Representatives. After leaving school, he worked as a journalist, writing for newspapers. In 1908 he travelled to London where he also worked as a journalist and in 1914 published a handbook on Australian rural life, The Opportunity in Australia to promote emigration to Australia. In 1915, Gullett became an official Australian correspondent on the Western Front. In July 1916, he joined the first Australian Imperial Force (AIF) as a gunner. From early 1917 he worked with Charles Bean collecting war records and later with the AIF as a war correspondent in Palestine. In 1919, he was briefly director of the Australian War Museum. He started writing volume VII of The Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918, covering the Sinai and Palestine Campaign, which he completed in 1922. In 1920, Billy Hughes (the Australian Prime Minister at the time) appointed him head of the Australian Immigration Bureau. He won a seat in Parliament for the Nationalist Party in 1925 and held it until his death in August 1940. In April 1939, Gullett became Minister for External Affairs in the first Menzies Ministry and Minister for Information from September 1939. He met with the Finnish Consul, Paavo Simelius a number of times in the weeks preceding the outbreak of the Winter War, and rather more frequently thereafter up until his death. He tended to defer to the Australian High Commissioner in London, the previously mentioned Stanley Melbourne Bruce, on matters of Foreign Affairs – and Bruce regarded the Russo-Finnish war in general as an unwelcome distraction which Australia should best avoid entanglement in.

Image sourced from: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/c ... ullett.jpg

Sir Henry Somer Gullett KCMG (26 March 1878 – 13 August 1940) was an Australian Cabinet Minister and member of the House of Representatives. After leaving school, he worked as a journalist, writing for newspapers. In 1908 he travelled to London where he also worked as a journalist and in 1914 published a handbook on Australian rural life, The Opportunity in Australia to promote emigration to Australia. In 1915, Gullett became an official Australian correspondent on the Western Front. In July 1916, he joined the first Australian Imperial Force (AIF) as a gunner. From early 1917 he worked with Charles Bean collecting war records and later with the AIF as a war correspondent in Palestine. In 1919, he was briefly director of the Australian War Museum. He started writing volume VII of The Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918, covering the Sinai and Palestine Campaign, which he completed in 1922. In 1920, Billy Hughes (the Australian Prime Minister at the time) appointed him head of the Australian Immigration Bureau. He won a seat in Parliament for the Nationalist Party in 1925 and held it until his death in August 1940. In April 1939, Gullett became Minister for External Affairs in the first Menzies Ministry and Minister for Information from September 1939. He met with the Finnish Consul, Paavo Simelius a number of times in the weeks preceding the outbreak of the Winter War, and rather more frequently thereafter up until his death. He tended to defer to the Australian High Commissioner in London, the previously mentioned Stanley Melbourne Bruce, on matters of Foreign Affairs – and Bruce regarded the Russo-Finnish war in general as an unwelcome distraction which Australia should best avoid entanglement in.

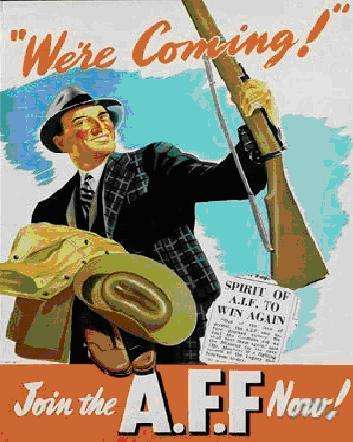

However, the Press and the Public were not to be denied and the public campaign orchestrated by the Assistance Organization grew every more vociferous and intense. The headlines of the major newspapers grew ever more critical of the Government, steps by which Volunteers could reach Finland and join the fight were articulated, Members of Parliament were pressured by their constituents and questions began to be asked. The official Opposition, the Labour Party, stepped into the fray in support of the dispatch of Volunteers. "Not a token force, but a substantial number of Volunteers who can make a real difference" stated Scullin. In this, many members of the Labour Party had been influenced by the strongly stated views of Bob Santamaria. Within the governing coalition, many MP's, pressured by their constitutents, began to press for approval and support for the dispatch of a Volunteer Force. Spurred on by the increasingly bad press the Government was receiving, the Australian Prime Minister, Robert Menzies made the decision, publicly announced in early January 1940, that two Battalions of Australian Volunteers together with supporting troops and a Field Hospital and Ambulance Unit would be raised and dispatched to Finland – and that this would occur within days. Dr. Lewis Nott was placed in charge of all medical units to be raised and it was stated that volunteers would be accepted from both Regular Officers, the Citizen Force and the A.I.F as well as from civilians.

The implication was made that preparations had been underway for some time but the need for secrecy had meant that the public could not be informed until certain prepatory actions had been taken. This was of course nonsense, but it served to assuage the media and the public. Menzies’ announcement stated that in the interests of speedy and large-scale assistance to Finland, men without prior military training would be accepted and that Volunteers from the AIF and the Militia could apply through the Australia-Finland Assistance Organisation. The Organisation of course had no real capability in place to handle such recruiting and processing of volunteers and the situation moved rapidly towards farcical. Menzies however, was not Prime Minister of Australia for nothing. Army Headquarters were instructed to second Officers and NCO’s to the Australia-Finland Assistance Organisation and carry out the assessment and selection of Volunteers, who were to be gathered in Melbourne for dispatch by sea within a fortnight. Organisation of the men into units would take place in Melbourne prior to departure.

The Army Command, taken completely by surprise and not consulted by Menzies before his announcement and his demands on the Army, scrambled to put some sort of structure in place to deal with what was now a fait accompli – particularly as Menzies had made it more than plain that this was something that needed to be seen to be done quickly and efficiently. At the same time, rapid decisions needed to be made on the size of the Volunteer unit, the numbers of men to be sent, equipment to be provided, shipping, and all the minutiae of dispatching a small and self-contained military force that politicians take for granted when they make political decisions regarding military matters.

Image sourced from: http://www.anzacsite.gov.au/5environmen ... 1939_l.jpg

Volunteers for the Australian Finland Force at the Melbourne Showground, early January 1940

Image sourced from: http://www.anzacsite.gov.au/5environmen ... 1939_l.jpg

Volunteers for the Australian Finland Force at the Melbourne Showground, early January 1940

The miracle was that the Australian Army succeeded. Exactly two weeks from Menzies’ announcement, a small convoy of Finnish merchant ships, some of them hastily converted into rudimentary troop ships, departed Melbourne unescorted with some 5,150 volunteers jammed on board but with no equipment other than a few hundred old Lee-Enfield .303 Rifles. The Australian Army had no artillery, mortars, AA guns or Anti-Tank guns to speak of, very few machineguns and there was a shortage even of the old .303 Rifles. In the short time between the announcement of the volunteer force and departure, a flurry of telegrams took place between Australia and Finland, the result of which was that the Finns were to arm and equip the Australians (and indeed, the Commonwealth Division) from their war reserves. This would mean that the Division would more than likely go into battle using the old Mosin-Nagant Rifles that the Maavoimat had been replacing as fast as possible with the newer semi-automatic Lahti-Salaranta SLR. The Australian Government howevever, was more concerned with getting the volunteers on their way than in how the Finns would manage to provide them with weapons and equipment (although the ladies of the CWA did ensure the volunteers were plentifully equipped with warm clothing, coats, hats, scarves, mittens and felt-lined boots. They might have no rifles or machineguns, but at least they would be warm in their Australian woollies).

The announcement that volunteers were actually being dispatched aroused the patriotic fervour of the Australian people – and the Australia-Finland Assistance Organisation found itself flooded with more volunteers than could be handled and further donations of money and materials. At the same time the Australian Government stating that the Government was committed to paying outright for all travel costs, the provision of uniforms as well as paying an allowance to the Volunteers – which were in fact the majority of the costs). As mentioned in an earlier post, Ford Australia very publicly donated 250 Ford trucks at cost straight of the Geelong Assembly line and had these crated for shipment to Finland, together with 50 Ambulances which were donated outright, with the fitting out as specialist Ambulance trucks being carried out by Ford workers on a voluntary basis. The Australian Pharmaceutical and Medical Supplies industry provided large quantities of medical and pharmaceutical supplies at cost and these were transported to Melbourne by the Railways free of charge where they were sorted and packed by volunteers. In addition to the shiploads of Volunteers and accompanying military and medical cargo, shiploads of Australian wheat, frozen mutton and lamb and canned meat were dispatched, paid for by the Assistance Organisation. The Finnish ships would proceed together as a small convoy to Cape Town and thence to the UK, where they would be routed to a suitable port in Norway for unloading.

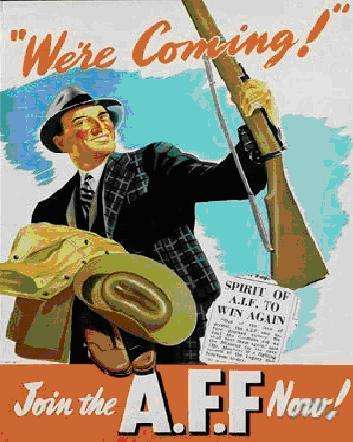

Image sourced from: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/c ... 333%29.jpg

Recruiting Poster for the Australian Finland Force - “Join the A.F.F. Now!” The recruiting poster depicts a happy young man in civilian clothes, holding an Army uniform and rifle, the newsclip in the background refers to the fighting prowess of the Australian Infantry. Such was the popularity of the cause that there were three times as many Volunteers as places, the standard of selection was thus high.

Image sourced from: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/c ... 333%29.jpg

Recruiting Poster for the Australian Finland Force - “Join the A.F.F. Now!” The recruiting poster depicts a happy young man in civilian clothes, holding an Army uniform and rifle, the newsclip in the background refers to the fighting prowess of the Australian Infantry. Such was the popularity of the cause that there were three times as many Volunteers as places, the standard of selection was thus high.

Image sourced from: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/c ... -01%29.jpg

Five women bid farewell to one of the last troop ships carrying the Australian Volunteers as it leaves Melbourne in late January 1940, bound for Finland. The Volunteers would take seven weeks by sea to reach Petsamo, arriving in late March 1940

Image sourced from: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/c ... -01%29.jpg

Five women bid farewell to one of the last troop ships carrying the Australian Volunteers as it leaves Melbourne in late January 1940, bound for Finland. The Volunteers would take seven weeks by sea to reach Petsamo, arriving in late March 1940

With the dispatch of the Volunteers to Finland, the Australian Government breathed a great sigh of relief and turned its collective attention back to the “real” war. Public opinion was assuaged. The newspapers praised the decisiveness of the Prime Minister and the War Cabinet, then continued to report on the progress of the Russo-Finnish War and the ANZAC Volunteers already in Finland. The Australia-Finland Assistance Organisation continued its work, albeit at a lesser pitch of fervor and intensity.

Next Post: The Commanding Officers of the Australian Volunteer Units